Prologue-Sam Pascoe, American scholar. Each of the four gospels in the Bible shows radically different ideas about who Jesus was, what he taught, and what his family origins were. This fact is completely undeniable and yet was almost completely ignored until the Enlightenment hit Germany in the late 1700s, ushering in the first “quest” for the historical Jesus. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus is portrayed as a reluctant Messiah who tries to use his powers of healing without calling any attention to himself, often telling both humans and demons he meets to keep quiet about the secret that he is the Messiah. The Gospel of John starts by saying that Jesus was the Word of God that brought the world into being, and has Jesus proclaiming openly in the streets that all must accept him as the one and only Son of God in order to have eternal life. The Gospel of Mark makes no mention of Jesus having a father when it lists all his family members (6:3) and even says that his mother and brothers believed he was crazy (3:21), but the gospels of Matthew and Luke say that Jesus was born of the virgin after one of his parents is given a divine revelation (Joseph in Matthew; Mary in Luke). The Gospel of Luke focuses almost completely on the apostle Paul after Jesus’ death in Acts of the Apostles and emphasizes equality between Jew and Gentile while the Gospel of Matthew focuses more on Old Testament prophecies and portrays Jesus as a new Moses. While the first three gospels, called the Synoptic gospels, center on moral philosophy, the Gospel of John uses Jesus to speak polemic against Jews who don‘t accept him as being one with God. The Jesus of the Synoptics expresses his teachings through parables and mostly talks about the coming Kingdom of God. John’s Jesus tells no parables, instead using rhetoric to glorify himself while saying almost nothing about the coming Kingdom. Even the day Jesus is crucified is different, with the Gospel of John placing it on Passover and the other three showing Jesus to have celebrated Passover in the form of the Last Supper the day before he died. “Inasmuch as certain men have set the truth aside, and bring in lying words and vain genealogies, which, as the apostle says, ‘minister questions rather than godly edifying which is in faith,’ and by means of their craftily-constructed plausibilities draw away the minds of the inexperienced and take them captive, [I have felt constrained, my dear friend, to compose the following treatise in order to expose and counteract their machinations.] These men falsify the oracles of God, and prove themselves evil interpreters of the good word of revelation. They also overthrow the faith of many, by drawing them away, under a pretence of knowledge, from Him who rounded and adorned the universe; as if, in fact, they had something more excellent and sublime to reveal, than that God who created the heaven and the earth, and all things that are therein. By means of specious and plausible words, they cunningly allure the simple-minded to inquire into their system; but they nevertheless clumsily destroy them, while they initiate them into their blasphemous and impious opinions respecting the Demiurge; and these simple ones are unable, even in such a matter, to distinguish falsehood from truth.” In a list of Christian heresies, he describes the beliefs and practices of each sect: followers of Simon the Magus, Marcion, Valentinus, Tatian, Menander, Saturninus, Basilides and offshoots, Carpocrates and offshoots, Cerinthus, the Ebionites, the Nicolaitanes, followers of Cerdo, Encratites, Barbeliotes, Borborians, Ophites, Sethians, and Cainites. The accusations of deviant sexual practices made against some of the sects, like the Valentinians, mirror the accusations Roman pagans had long made against Christian communities. Other sects, like the Encratites, are criticized for requiring lifelong celibacy. From what Irenaeus describes, the majority of Christianity at this time was Gnostic. The Latin Church Father Tertullian complained that “the whole universe” was filled with Marcionites. The Christian philosopher Justin Martyr lamented that to be a Christian in the Jewish city of Edessa meant being a Marcionite and that the Samaritans in his homeland all held to the beliefs of Simon the Magus, who Irenaeus calls the father of all heresy.  An engraving of St. Irenaeus (c. 130-202) Irenaeus also wrote a refutation of the Valentinian interpretation of the fourth gospel, the Gospel of John. This fragment of Irenaeus’ lost treatise De Ogdoad, or “On the Eight Spirits,” focused on refuting Valentinus’ belief that the world was created by four pairs of angels. In it he describes to what horror his teacher, Polycarp, would have taken these ideas. Polycarp was the bishop of Smyrna, in Turkey, and is called “hearer” of the disciple John. The fourth century bishop of Caeserea, Eusebius, quotes Irenaeus as saying: These opinions, Florinus, that I may speak in mild terms, are not of sound doctrine; these opinions are not consonant to the Church, and involve their votaries in the utmost impiety; these opinions, even the heretics beyond the Church's pale have never ventured to broach; these opinions, those Presbyters who preceded us, and who were conversant with the Apostles, did not hand down to thee. For, while I was yet a boy, I saw thee in Lower Asia with Polycarp, distinguishing thyself in the royal court, and endeavoring to gain his approbation. For I have a more vivid recollection of what occurred at that time than of recent events (inasmuch as the experiences of childhood, keeping pace with the growth of the soul, become incorporated with it); so that I can even describe the place where the blessed Polycarp used to sit and discourse his going out, too, and his coming in his general mode of life and personal appearance, together with the discourses which he delivered to the people; also how he would speak of his familiar intercourse with John, and with the rest of those who had seen the Lord; and how he would call their words to remembrance. Whatsoever things he had heard from them respecting the Lord, both with regard to His miracles and His teaching, Polycarp having thus received [information] from the eye-witnesses of the Word of life, would recount them all in harmony with the Scriptures. These things, through, God’s mercy which was upon me, I then listened to attentively, and treasured them up not on paper, but in my heart; and I am continually, by God’s grace, revolving these things accurately in my mind. And I can bear witness before God, that if that blessed and Apostolical Presbyter had heard any such thing, he would have cried out, and stopped his ears, exclaiming as he was wont to do: ‘Oh good God, for what times hast Thou reserved me, that I should endure these things?’ And he would have fled from the very spot where, sitting or standing, he had heard such words. This fact, too, can be made clear, from his Epistles which he dispatched, whether to the neighboring Churches to confirm them, or to certain of the brethren, admonishing and exhorting them. St. Papias, a companion of Polycarp’s was the bishop of Hierapolis, another city in western Turkey a short distance east of Smyrna, now Pumukkale. Although none of Papias’ works have survived, many of his sayings have been quoted by later church fathers. Irenaeus took from Papias the idea that Mark was the interpreter of Peter, an idea believed to go back to John. Some scholars lay some doubt on the word of St. Papias, however, due to some of the things he says. Apollinaris, bishop of Laodicea, taking from Papias’ 4th book of Expositions, quotes him as saying that after Judas died, his head “bloated to greater than the width of a wagon trail and his eyes were lost in the flesh, and that the place where he died maintained a stench so bad that no one, even to his own day, would go near it.” Eusebius himself considered him to be “a man of small mental capacity.” Irenaeus saw Christ as recapitulating the stages of human life, from infancy to old age. But this hardly has good fitting with either the historical standpoints offered in the gospels. Due to chronological constraints within the gospels of Matthew and Luke, almost everyone believes Jesus was crucified around the age of 30. But it does sound like the account Irenaeus gave of his teacher, Polycarp, saying that “he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and when, a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he learned from the apostles.” The Martyrdom of Polycarp, written around the 150s, places Polycarp’s martyrdom at the age of 86. The same thing would be said of the disciple John, who was also believed to have be martyred around the age of 90, a firm necessity in order for John to be able to write his gospel 60 years after Jesus‘ death! Irenaeus claims John saw “the Word of Life,” yet Eusebius of Caeserea didn’t believe him and made a distinction between John the Apostle and Irenaeus’ teacher, John the Elder. Eusebius gives a quote from a lost work of St. Papias, which makes reference to two different Johns: “But I shall not be unwilling to put down, along with my interpretations, whatsoever instructions I received with care at any time from the Presbyters, and stored up with care in my memory, assuring you at the same time of their truth. For I did not, like the multitude, take pleasure in those who spoke much, but in those who taught the truth; nor in those who related strange commandments, but in those who rehearsed the commandments given by the Lord to faith, and proceeding from truth itself. If, then, any one who had attended on the Presbyters came, I asked minutely after their sayings-- what Andrew or Peter said, or what was said by Philip, or by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the Lord’s disciples: which things Aristion and the Presbyter John, the disciples of the Lord, say. For I imagined that what was to be got from books was not so profitable to me as what came from the living and abiding voice.” Drawing from this text, Eusebius concluded the first John was the disciple and gospel writer since he was listed with the other disciples from the gospels, and that John the Elder was the teacher of Papias. According to him, John the disciple had written the gospel and John the Elder had written the Book of Revelation and the latter two epistles signed “John the Elder.” Although Eusebius is called the Father of Church History and was instrumental in the defining of Christian orthodoxy at the Council of Nicaea, the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia says: “With all Catholic authors, we consider that either Eusebius alone, or Papias and Eusebius erred, and that Irenaeus and the rest of the Fathers were right, in fact we lay the blame at the door of Eusebius.” No wonder he didn’t become a saint. The Latin church father St. Jerome, who also quotes that verse from Papias, was sent to the city of Ephesus (in what is now Turkey) to translate the Greek version of the scriptures into the Latin Vulgate. He said that in the city “there are two memorials of this same John the Evangelist” and that half the people there believed John the Elder was the author of the Gospel of John, although Jerome himself didn’t think this was true. “The mountain represents the Devil, or his world, since the Devil was one part of the whole of matter, but the world is the total mountain of evil, a deserted dwelling place of beasts, to which all who lived before the law and all Gentiles render worship. But Jerusalem represents the creation or the Creator whom the Jews worship… The mountain is the creation which the Gentiles worship, but Jerusalem is the creator whom the Jews serve. You then who are spiritual should worship neither the creation nor the Demiurge, but the Father of Truth. And he [Jesus] accepts her [the Samaritan woman] as one of the already faithful, and to be counted with those who worship in truth. “ In the Gospel of John, “You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is of the Jews.” Heracleon says: “The ‘you’ stands for the Jews and the Gentiles… We must not worship as the Greeks do, who believe in the things of matter, and serve wood and stone, nor worship the divine as the Jews. They who think they alone know God do not know him, and worship angels, the month, and the moon. In the Gospel of John: “But the hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for such the Father seeks to worship him.” Heracleon says: “For the previous worshippers worshipped in flesh and in error him who is not the Father... They worshipped the creation and not the true creator [Romans 1:25], who is Christ, since ‘all things came into being through him, and apart from him nothing came into being.’ [John 1:3]” Although none of these interpretations are particularly convincing, concepts such as the Logos (or Word) are nevertheless more at home within the Neo-Platonic worldview of Gnosticism, and this early commentary on John does provide evidence for the Gospel of John being used by Gnostics. A far more likely origin for the Gospel of John is the Jewish Gnostic sect known as the Cerinthians, who lived in ancient Galatia, modern-day Turkey. Irenaeus states that John’s purpose in Ephesus was to combat the heresy of Cerinthus, who also was linked to a Gnostic Gospel of John. In Chapter 11 of his third book, he writes: “John, the disciple of the Lord, preaches this faith, and seeks, by the proclamation of the Gospel, to remove that error which by Cerinthus had been disseminated among men, and a long time previously by those termed Nicolaitans, who are an offset of that ‘knowledge’ falsely so called, that he might confound them, and persuade them that there is but one God, who made all things by His Word; and not, as they allege, that the Creator was one, but the Father of the Lord another; and that the Son of the Creator was, forsooth, one, but the Christ from above another, who also continued impossible, descending upon Jesus, the Son of the Creator, and flew back again into His Pleroma [Fullness]…” Despite the fact that John’s stated mission was to “confound” and “persuade” the Cerinthians, the proclamation against Cerinthus was apparently not enacted through direct communication with the man. According to Irenaeus, Polycarp once told him that John so feared Cerinthus that upon seeing him at a bath house in Ephesus, John turned away, saying, “Let us flee; less the building fall down; for Cerinthus, the enemy of truth, is inside!” “He was a Greek-speaking Jewish Christian of the mid-first century, who was deeply familiar with the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible, and who regarded Jesus as a new or antitypical Moses. We know this because of the importance he attaches to the Greek word semeia, ‘signs.’ Jesus’ miracles are ‘signs’ that cause belief in him, an idea borrowed from the Septuagint account of Moses’ miracles: Moses ‘performed the signs [epoiese at semeia] before the people. And the people believed [episteusen]” (Ex. 4:30-31 LXX). Likewise at Cana in Galilee, Jesus ‘performed the first of the signs [epoiesen archen ton semeion], and his disciples believed [episteusan]” (John 2:11). According to the author of the Signs Gospel, the ‘signs Jesus performed [semeia epoiesen ho Iesous]’ were written down in order that readers ‘may believe [pisteute] that Jesus is the Christ” (John 20:30, 31).” (p.115) Helms argues that the Signs gospel pre-dated the Synoptic gospels and drew upon oral traditions similar to the ones Mark used, but also used pagan traditions in the story of Jesus changing water to wine from the Greek god Dionysus and the resurrection of Lazarus as an analogy to the resurrection of the Egyptian god “El-Osiris.” Many Hellenisitic mystery cults were centered on the Dionysus and Osiris during this time period. Both of them were originally fertility gods whose myths of death and resurrection had traditionally imitated the life cycle of the seasons which had evolved into religions that promised resurrection by the sacramental eating of bread and wine which symbolized the flesh and blood of the god. Fortna had described the location of the author of the Signs gospel as a Greek-speaking Jewish synagogue in a city that had a “cosmopolitan atmosphere,” which Helms aptly identifies as Alexandria. Helms argues it was first written by a sect of Jewish Christianity analogous to the Egyptian “John the Baptist” sect perceived by “Luke” to be outdated, as mentioned in Acts 19. “To look to future eschatology is implicitly to argue the incompleteness of Jesus, that he needs to come back in order to finish his work, while realized eschatology fully accepts Jesus’ final cry of triumph: ‘It is finished!’ (John 19:30). Indeed, ever since the groundbreaking commentary on the Fourth Gospel by Rudolf Bultmann (first published in 1941 as Das Evangelium des Johannes), it has become widely accepted that “John,” the anonymous reviser of the Signs Gospel, no longer expected any apocalyptic events in the future, since God’s decisive offer of salvation through faith in Jesus was all that was needed. As it happened, however, John’s attempt to re-define eschatology was so radical that it failed (being smothered over by John 2, who re-introduced future eschatology back into the Fourth Gospel…); and sadly the effect of this re-introduction has been that much of contemporary Christianity remains saddled with an always self-disconfirming claim (‘Jesus is coming soon‘).” The second John, also referred to as “the Redactor,” wrote against the same kind of Christians who didn’t believe in the idea of consuming the flesh and blood of Jesus during Communion. When John 2 wrote about the Christians who found the teaching “hard” and withdrew into a different sect, he was describing the division within his own community (6:52). The sacrament would have been particularly problematic for two groups of people: Jews, who would find the symbolic consumption of blood as very not kosher, and Gnostics, who focused on spiritual purity over material sacraments. So Jewish Gnostics like the Cerinthians are a very likely target for the polemic of John 2. Epiphanius, the Bishop of Salamis (Cyprus) and one of the first heresiologists following the official defining of Orthodoxy at Nicaea wrote in his anti-heresy book disputed the Gnostics' claim that Cerinthus wrote the Gospel of John. Helms takes this as further proof that the Gospel of John had been used by both sides in that particular theological battle: “So the gospel attributed, late in the second century, to John at Ephesus was viewed as an anti-gnostic, anti-Cerinthean work. But, very strangely, Epiphanius, in his book against the heretics, argues against those who actually believed that it was Cerinthus himself who wrote the Gospel of John! (Adv. Haer. 51.3.6). How could it be that the Fourth Gospel was at one time in its history regarded as the product of an Egyptian-trained Gnostic, and at another time in its history regarded as composed for the very purpose of attacking this same gnostic? I think the answer is plausible that in an early, now-lost version, the Fourth Gospel could well have been read in a Cerinthean, gnostic fashion, but that at Ephesus a revision of it was produced (we now call it the Gospel of John) that put this gospel back into the Christian mainstream.” So there are also at least three versions of the Gospel of John. The first is the Signs Gospel, which was probably written in Egypt, one linked to Cerinthus (John 1), and the version that survived, Irenaeus‘ version (John 2). In the 26th chapter of his first book, Irenaeus writes: “Cerinthus, again, a man who was educated in the wisdom of the Egyptians, taught that the world was not made by the primary God, but by a certain Power far separated from him, and at a distance from that Principality who is supreme over the universe, and ignorant of him who is above all. He represented Jesus as having not been born of a virgin, but as being the son of Joseph and Mary according to the ordinary course of human generation, while he nevertheless was more righteous, prudent, and wise than other men. Moreover, after his baptism, Christ descended upon him in the form of a dove from the Supreme Ruler, and that then he proclaimed the unknown Father, and performed miracles. But at last Christ departed from Jesus, and that then Jesus suffered and rose again, while Christ remained impassible, inasmuch as he was a spiritual being. What Irenaeus says here should give the reader pause for thought. Here it is, 150 years after Jesus’ death and Judeo-Christian orthodoxy is being fought from present-day France against the “Judaic” Christian heretics from Jerusalem? The Synoptic gospels portray Jesus as a circumcised Jewish rabbi, who more-or-less followed the laws of Moses. The epistles of Paul in the New Testament, however, said that Christ’s death brought an end to the Old Testament laws. Irenaeus argued that although most of the Old Testament laws were cancelled by Christ’s death, the Ten Commandments were not. But nothing has brought modern scholars to believe Jesus preached for the dissolution of the old Jewish laws in the Synoptics, and Jerusalem certainly was “the House of God” in the Old Testament. So what was so different about them? Ebionites: By this name were designated one or more early Christian sects infected with Judaistic errors.... Recent scholars have plausibly maintained that the term did not originally designate any heretical sect, but merely the orthodox Jewish Christians of Palestine who continued to observe the Mosaic Law. These, ceasing to be in touch with the bulk of the Christian world, would gradually have drifted away from the standard of orthodoxy and become formal heretics. A stage in this development is seen in St. Justin’s “Dialogue with Trypho the Jew,” chapter xlvii (about A. D. 140), where he speaks of two sects of Jewish Christians estranged from the Church: those who observe the Mosaic Law for themselves, but do not require observance thereof from others; and those who hold it of universal obligation. The latter are considered heretical by all; but with the former St. Justin would hold communion, though not all Christians would show them the same indulgence. St. Justin, however, does not use the term Ebionites, and when this term first occurs (about A. D. 175) it designates a distinctly heretical sect. The assertion made here is that the Ebionites living in Jerusalem, which according to Acts of the Apostles was the headquarters of the early Apostolic movement, and which the Father of Church History said was lead by relatives of Jesus, had become “infected with Judaistic errors” while the true inheritance of Christian history and philosophy was safely protected by a different culture and recorded in a different language, relying ultimately on John the Elder, whoever he is. The deep racial and cultural divide between the Gentile and Jewish church, as portrayed in the Acts and Paul's epistles gives good answer as to what kept Jerusalem from being “in touch with bulk of the Christian world.” “Paul belongs to the kind of Gnosticism that was fascinated by the Jews and Judaism, and sought to weave them both into its pattern, usually with anti-Semitic effect. The Torah, in this kind of scheme, is acknowledged to be of supernatural origin, but it comes from the wrong supernatural source. Yet the Torah, for this kind of Gnostic, contains a secret message: despite itself, it gives information contained in the Hebrew Bible there are hints of an alternative tradition, by-passing the authority of the Jews and Judaism. Thus we find Gnostics concentrating on figures in the Bible who are not Jews, but who nevertheless seem to have authority: such as Seth, the son of Adam born after the murder of Abel by Cain; or Enoch, reputed to have been taken alive into heaven; or Melchizedek, the priest of the Most High who was not of the Jewish Levitical priesthood. On figures such as these it was possible to construct the fantasy of an alternative tradition, stemming not from the Jewish God, but from the High God above whose message far transcended Judaism. Cerinthus is Jewish enough for many scholars to refer to him as Semi-Gnostic, although Tertullian says they identify Yahweh with the Demiurge instead of the High God, which would make him “fully” Gnostic like the Cainites. Tertullian assumes that the Ebionites were led by one Ebion, but there is heavy doubt on this. In the 3rd chapter of Against All Heresies, Tertullain writes: “After him [Carpocrates] brake out the heretic Cerinthus, teaching similarly. For he, too, says that the world was originated by those angels; and sets forth Christ as born of the seed of Joseph, contending that He was merely human, without divinity; affirming also that the Law was given by angels; representing the God of the Jews as not the Lord, but an angel. If Paul’s branch of Christianity was that much different than James, why do church fathers like Irenaeus say they are almost identical to the Gnostic Cerinthians excluding the central question as to Yahweh being an angel or God? Shouldn't there be far more differences if one origianted from Hellisitic mystery cults and the other originated from Judea and Galilee? St. Epiphanius, writing in the 300s, also compares the Cerinthians to the Nazoreans and Ebionites: “Cerinthians, also known as Merinthians. These are a type of Jew derived from Cerinthus and Merinthus, who boast of circumcision, but say that the world was made by angels and that Jesus was named Christ as an advancement to a higher rank. Nazoraeans, who confess that Christ Jesus is Son of God, but all of whose customs are in accordance with the Law. Ebionites are very like the Cerinthians and Nazoraeans; the sect of the Sampsaeans and Elkasaites was associated with them to a degree. They say that Christ has been created in heaven, also the Holy Spirit. But Christ lodged in Adam [man] at first, and from time to time takes Adam [man] himself off and puts him back on- for this is what they say he did during his visit in the flesh. Although they are Jews, they have Gospels, abhor the eating of flesh, take water for God, and, as I said, hold that Christ clothed himself with a man when he became incarnate. They continually immerse themselves in water, summer and winter, if you please for purification like the Samaritans.” St. Irenaeus wrote that heretics who used the Gospel of Mark alone alleged that “Christ remained impassible, but that it was Jesus who suffered.” These same Christians believed that the baptism of Jesus was the point in which, as Mark says, “the Spirit descended on him like a dove,” providing the source of his healing power (1:10). They differentiated between Jesus and Christ and said that Christ was the Son of God by nature but Jesus was the Son of God by “adoption,” which has led to the belief being referred to as Adoptionism. Epiphanius attributes this belief to both the Cerinthians and the Ebionites. In The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, Prof. Bart Ehrman argues that the Adoptionist belief may date back almost to the time of Jesus. Adoptionism is categorized as one of the two forms of Monarchism, the belief that “the Lord is one” (12:29), as opposed to that of a Trinity. The second form of Monarchism is Modism, the belief that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three different modes of the same “person,” as opposed to the Orthodox belief that God is made up of three “persons.” An example of Modism is that of Sabellianism, taught by the Roman heretic Sabellius, until it died out during the 300s. Adoptionism is also looks to be related to Docetism, as both see a dual nature in Jesus the person and Christ the spirit, and may even be equivalent if the “illusionary” body of Docetism is taken to be symbolic of the temporary nature of matter. But a certain Cerinthus, himself being disciplined in the teaching of the Egyptians, asserted that the world was not made by the primal Deity, but by some virtue which was an offshoot from that Power which is above all things, and which yet is ignorant of the God that is above all. And he supposed that Jesus was not generated from a virgin, but that he was born son of Joseph and Mary, just in a manner similar with the rest of men, and that Jesus was more just and more wise than all the human race. And Cerinthus alleges that, after the baptism of our Lord, Christ in form of a dove came down upon him, from that absolute sovereignty which is above all things. And then, Jesus proceeded to preach the Unknown Father, and in attestation of his mission to work miracles. It was, however, the opinion of Cerinthus, that ultimately Christ departed from Jesus, and that Jesus suffered and rose again; whereas that Christ, being spiritual, remained beyond the possibility of suffering. According to Irenaeus and Epiphanius, the Ebionites considered Paul to be an apostate, and some modern interpretations also see Paul is the worst thing that ever happened to the original faith of Jesus. But aside from whether Paul was good or bad for Christianity, there has been a large increase in responsible critical research into early Christianity that sees a great divide between a more Jewish Jesus and a Pauline church whose beliefs were corrupted by the pagan mystery religions of the Roman Empire. Certainly it’s a breathtaking wonder how a movement could evolve from traveling disciples not being allowed bread or money while going out to exorcize people of evil spirits (as Mark 6:7 says) to the financial grandeur it‘s achieved for 1700 years. But if Gnosticism was a later addition, why do all the early church fathers say the Ebionites were so much like the other Gnostics? Were the Ebionites just being lumped in with the Gnostics? Why are other Pauline schools like the Marcionites and the Valentinians all holding similar ideas to Cerinthians regarding the Demiurge? Why do the Marcionites, Valentinians, and Encratite schools of Justin and Tatian hold the same restrictions against meat, alcohol and sex the Ebionites had? Why was this Jewish sect, which many scholars believe was represented the more original version of Christianity, still so Hellenistic?

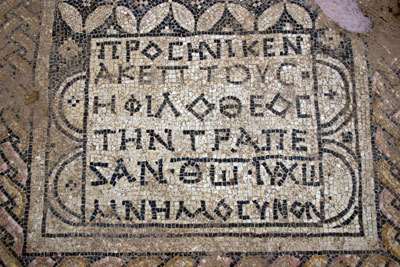

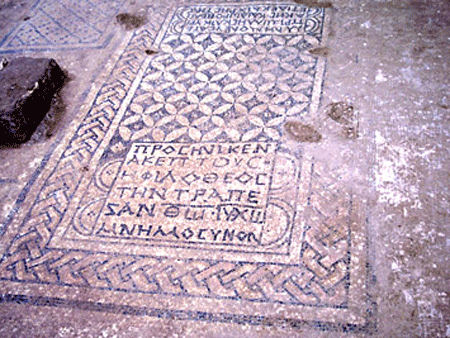

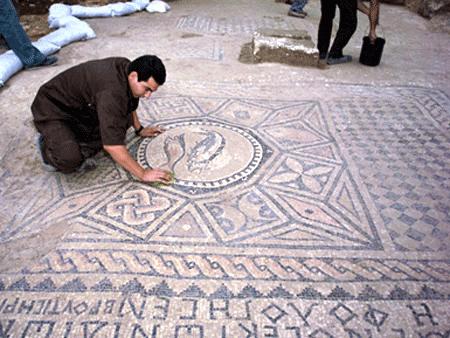

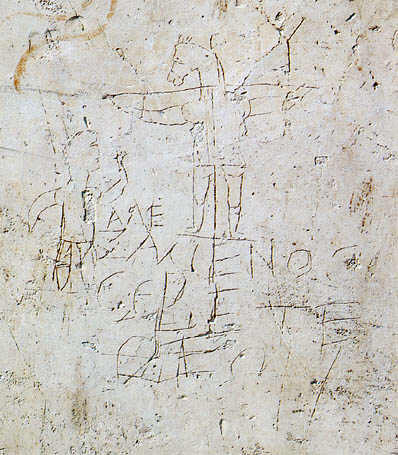

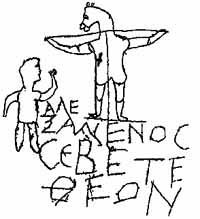

Even in Israel, where one would suspect ancient Christian artifacts would give evidence to the earlier Jewish roots of Christianity, we find evidence of Christianity having a very Hellenistic flavor. In 2005, Israeli prisoners unearthed an ancient Christian church near the city of Megiddo, the site of what was believed to be the last battle, hence the derivation of the name “Armageddon.” The area had once been the battleground where the great Biblical hero King Josiah of Judah was slain by an arrow when he tried to stop Pharaoh Necho from reinforcing Judah’s enemy, the Assyrians, to the north. His death ultimately brought about the fall of Judah and the Babylonian Captivity, to which the Book of Revelation refers to when talking of the Roman conquest of Judah. In Revelation, the angelic Jesus was to return to Megiddo for the final battle against the army of the Beast, whose number 666, is generally decoded as “Caesar Nero.”      manger found in horse stable at Tel-Megiddo site Other early evidence points to early Christians worshipping Jesus as God comes from Rome. What is probably the earliest representation of Jesus is the Alexamenos Grafitto, found etched into the plaster on a pillar in a guard room on Palatine Hill near the Circus Maximus and dated between 193 to 235 A.D. The carving portrays a man saluting a crucified donkey with the caption, “Ale-xamenos sebete theon, or Alexamenos worships [his] god.” Most scholars believe the engraving is meant as an insult, mocking a Christian Alexamenos for worshipping a crucified fool.   Engraving of man saluting crucified donkey Caption reads “Ale-xamenos sevete theon,” or Alexamenos worships [his] god” The symbol found on the first century objects excavated from Mt. Zion are of an even more fascinating sort of complexity. The symbol of the menorah, representing the Jews, combines with the fish, representing Christians, to form a Star of David, representing kingship. The symbol would seem to make the most sense as an attempt to combine that which was commonly believed to be separate. But were the teachings of Jesus really so different that even his Jerusalem followers believed it to be something separate to be combined with Judaism? Did Jesus really teach that he was “Lord of the Sabbath,” or use the flesh and blood metaphor during the Last Supper? Did his immediate followers really think he was God incarnate or was that just Paul adding elements from the pagan mysteries to it? This book will look into strange apple-and-tree nature of Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity and present evidence of a religious history of Christ that’s been lost, covered up, and forgotten on all sides for hundreds of years. |