Gilgamesh and Enkidu

“Patriotism ruins history.”

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, German poet, painter, and natural scientist

The Sumerian Heroic Age

According to the king lists, kingship remained in the city of Kish for 24,000 years after the flood (maybe 250 years in real life?), until it was taken to the city of Uruk during the reigns of “Dumuzi the Fisherman” and Gilgamesh. The kings of the first dynasty of Uruk were especially important to the Sumerian record keepers, who list epithets for the first five kings of the dynasty. The leading Sumerologist, Samuel Noah Kramer, refers to this early Uruk era as the “Sumerian Heroic Age,” paralleling the Heroic Age described by the early Greek poet Hesiod. The fifth king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, was especially important, not just in Sumerian mythology, but all the succeeding nations and empires for the next thousand years. But even though the kings of Kish were relatively unimportant compared to the forthcoming dynasty, the title “King of Kish” remained an important title for hundreds of years and was used even by kings who had no control of the city.

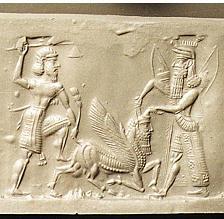

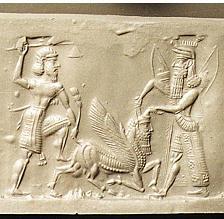

It was perhaps during the Kish dynasty that the Akkadians first infiltrated into northern Iraq, having been encouraged by the weakness of Sumerian authority after the Shurrupuk flood. There are 23 kings in the Kish dynasty who ruled after the flood, most of them with Semitic names. Although the preceding dynasty of Kish was no where near as popular as Uruk‘s warrior-kings, the pious 13th king of Kish, Etana, who is said to have flown up to heaven on the wings of an eagle, was of particular interest. Although only partially-missing Babylonian versions of the myth have been found, depictions of Etana riding the eagle are among the most popular Sumerian seals cut, some dating to the 2500’s B.C., proving that the story is much older. The fragmented myth is also corroborated by the Sumerian king lists which say that he “ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign lands.” The king lists have him as ruling either 635 or 1,560 years, and he is mentioned as residing in the netherworld in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Myth of Etana begins by talking of a city planned by the gods, probably Kish, and that they decided to make Etana the architect. Once again, the story begins with creation of the world and speaks of the revolt of the servant-gods, the Igigi, but this time it is the making of the first king, Etana, not of humankind, that restores order between heaven and earth:

The creators of the four world regions, establishers of all physical form,

By command of all of them the Igigi gods

Ordained a festival for the people

No king did they establish, over the teeming peoples,

At that time no headdress had been assembled, nor crown,

Nor yet scepter had been set with lapis.

No throne daises whatsoever had been constructed,

Against the inhabited world they barred the gates...

The Igigi gods surrounded the city with ramparts

Ishtar came down from heaven to seek a shepherd,

And sought for a king everywhere.

Innina came down from heaven to seek a shepherd,

And sought for a king everywhere.

Enlil examined the dais of Etana,

The man whom Ishtar steadfastly.…[broken off]

A shrine is built for the storm god Adad, with an eagle settling on it’s crown and a snake settling in it’s roots. The eagle almost certainly symbolizes the Elamite culture centered in the mountains of northwest Iran. Excavations of their capital, Susa, have shown the eagle totem to be the dominant religious motif of the city, and Adad is also known to be associated with the city. The snake in turn, probably represents the early Sumerians of the Eridu period, who worshipped the fish god Enki and the serpent goddess Nammu, or Tiamat. Just as the mountainous landscape of the Zagros Mountains in northwestern Iran make for a natural background to the Elamite eagle cult, the swamplands of southern Iraq make for a logical environment for the snake and fish totems of Eridu and the Enki cult.

The eagle and the snake decide to swear an oath of friendship to the Shamash, or in Sumerian, Utu, the sun god of justice. They swear by the netherworld that neither should transgress “the limits of Shamash” on pain of dishonor and death. This probably represents a border treaty made between the Sumerians and the Elamites. After sharing many hunting trips together, the eagle plotted evil in his heart and flew down and ate the serpent’s children against the warnings of one of his sons. Upon finding his children eaten, the snake cried out, “I trusted in you, Oh warrior Shamash! I was the one who gave provisions to the eagle, now… my nest gone, while his nest is safe. My young are destroyed, while his young are safe… The eagle must not escape from your net, that malignant Anzu [giant bird] who harbored evil against his friends!” Shamash tells the snake to cross the mountain where he would find a bull that the sun god had caught for him. Once there he was to open up the bull’s insides and set an ambush within it’s belly, so that when all the birds of heaven came down to feast, he could grab the eagle, rip off it’s feathers and tail and throw it in a pit to starve to death. Although the bull is a very popular metaphor for all the Sumerian gods, it is perhaps most commonly associated with Enlil, the god of Nippur. Kish and Nippur have had a long relationship with one another, since it was Nippur who had to give acknowledgement for the important “King of Kish” title. Thus, this may represent the idea that the Sumerians took control of Kish and set an ambush for the Elamites.

Although the exceedingly wise son of the eagle warns his father that the snake would be lying in wait for him, the eagle sees how the other birds are eating unhampered and so flies down and gets caught. The eagle begs for mercy, offering a king’s ransom, but the snake tells him if he let him go then Shamash’s rightful punishment would instead turn on him. The snake rips off the eagle’s feathers and tail and throws it into a pit. For days the eagle begs Shamash for help, but the sun god responds saying, “You are wicked and have done a revolting deed. You committed an abomination of the gods, a forbidden act. Were you not under oath? I will not come near you. There, there! A man I will send you will help you.”

Meanwhile, Etana was beseeching Shamash day after day, asking for a child:

“Oh Shamash, you have dined from my fattest sheep!

Oh Netherworld, you have drunk of the blood of my sacrificed lambs!

I have honored the gods and revered the spirits,

Dream interpreters have used up my incense,

Gods have used up my lambs in slaughter.

Oh Lord, give the command!

Grant me the plant of birth!

Reveal to me the plant of birth!

Relieve me of my burden, grant me an heir!”

Shamash directs Etana to the pit where he rescues the eagle. Here, the text becomes fragmented, but another version has the eagle interpreting Etana’s dreams for him. The eagle then offers to fly Etana to the gates of the seven Anunnaki gods. This particular myth lists them as: Anu, Enlil, Ea (Enki), Suen (Nanna), Shamash (Utu), Adad (Hadad), and Ishtar (Inanna). After flying Etana a league into the air, the sea looks like a stream; after a second league, the land becomes a hill; and after a third league, the sea becomes a gardener’s ditch. Suddenly, Etana becomes afraid of heights and asks the eagle to return him to his city, so the eagle begins to swoop back down. Although the ending of the story is lost, it can be assumed that Etana was successful in attaining the plant of birth, since the king lists say that his son Balih succeeded him.

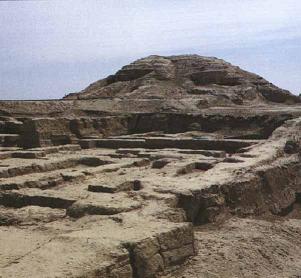

The second to last ruler in the Kish dynasty was Enmebaragesi, whose name appears on a small fragment of an alabaster vase found by a German Sumerologist named D.O. Edzard working in Baghdad. Enmebaragesi was both a priest, or En, and king, or Lugal, and is recorded on the king lists as having made Elam submit. He is believed to have controlled an area all the way from the Mediterranean Sea to the Zagros Mountains on the Iranian border. But by the time Enmebaragesi had ascended the throne in Kish, a rival kingship had been set up by “Meshkiagasher, Son of Utu” in E-Anna, “the House of Heaven,” one of Uruk’s two districts. The district was named after the ziggurat of the same name, a pyramid-shaped temple tower built by the Sumerians and copied by the Elamites, Babylonians, and Assyrians. Ziggurats ranged from two to seven stories and were made out of sun-baked mud brick with fire-burned bricks on the outside. Unlike pyramids, the tops were flat and they usually had two giant ramps coming up from either side of the entrance. They were believed to be the dwelling places for the gods and only priests were allowed entrance into their inner sanctuaries.

Ziggurat of E-Anna, “House of Heaven,” in Uruk

All nine of the epic Sumerian adventures featuring heroes that have been recovered are based on the kings from Meshkiagasher’s Uruk dynasty, probably due to their ability to bring power back to the Sumerian side of the Euphrates. His son, Enmerkar, is credited with building up the city of Uruk, which seems to have included the city’s other district, Kulaba. The longest Sumerian epic recovered is the story of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, which opens with praises for Uruk-Kulaba and boasts that the temple of Inanna was even older than Dilmun. Although badly damaged, the epic was restored using 20 tablets and many other fragments. It tells of how Enmerkar performed three miraculous events in order to make the Lord of Aratta, Ensuhgirana, submit to him. “Aratta” is believed to be the Elamite capital of Susa, which sits on the bank of the Karkheh Kur river, and, as the texts suggest, is at the foot of the mineral-rich Zagros mountains. The Karkheh Kur river also lent it’s name to the Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great, also known as Kor-esh, who allowed the Jews held captive in Babylon to return to Jerusalem in 539 B.C.

At the start of the epic, Enmerkar sends a messenger to Aratta, telling him that the lord was to donate gemstones to adore the temple in Uruk and Eridu. The messenger travels over seven mountains to get to the city, which seems to parallel the Sumerian journey through the netherworld of Kur consisting of seven gates. The Sumerian word kur has several meanings, including: land, country, mountain, mound, or the netherworld. This may have derived from the sight of a mountainous river like the Karkkheh disappearing into the mountainside, which may have been interpreted by ancient man as leading into the netherworld. In Hesiod’s book, Theogony, the Queen of the Underworld, Styx, lives in a “glorious house vaulted over with great rocks and propped up to the heavens all round with silver pillars.” These kinds of mythical pillars are often represented as either holding up the land over the netherworld or holding up the heavens over the earth. The Sumerian ziggurats were often built in seven layers, each one representing one of the Seven Heavens. In the First Book of Enoch, the prophet describes seeing a “mountain of fire flashing both by day and night” followed by “seven splendid mountains, which were all different from each other. Their stones were brilliant and beautiful; all were brilliant and splendid to behold; and beautiful was their surface.” (24:1). The concept of seven heavens and seven hells can also be found in the Zoroastrian religion of Persian Iran and the Muslim Qu’ran (15:44, 17:44).

When Enmerkar’s messenger tells the Lord of Aratta to submit, the Iranian king sends message back that he would only do so if Enmerkar provided grain for the famine they were experiencing, only instead of bringing it bags, it was to be brought in nets. Yet the grain goddess Nisaba, who may be another incarnation of Ninhursag, helps him grow grain so fermented it doesn’t fall through a net. When Enmerkar sends another messenger demanding that Ensuhgirana accept the sceptre of Uruk, the king replies he would only submit to a sceptre made of something called kumea. Enki helps Enkmerkar grow a sceptre of kumea, astonishing the Lord of Aratta again. For the last feat, the Lord of Aratta suggests a tournament between “ones that have a shirt with no color on it,” presumably meaning neutral contestants. Enmerkar’s reply is so long that his messenger can’t remember it all, and the king of Uruk is said to have invented writing on clay tablets so that the messenger could remember everything. Despite this claim, archaeological evidence has shown that cuneiform writing had preceded the period by hundreds of years.

The ending to this epic is lost, but another version skips Enmerkar’s first two feats and tells how a wizard’s duel is set up to decide the conflict. Not wanting to submit to Enmerkar even at the cost of his city, he hires a sorcerer who goes to Uruk. By talking to the animals, the sorcerer finds the cow and goat whose milk and cheese was eaten by Nisaba and enacts a spell that dries up their udders. A wise woman named Sagburru comes to Uruk and faces off with Ensuhgirana’s sorcerer on the Euphrates river. The duel was somewhat like a monster battle in the Japanese game, Pokémon, consisting of the two magicians throwing ingredients, perhaps fish spawns, into the river, which would then turn into different animals. When Ensuhgirana’s sorcerer makes a carp, Sagburru makes an eagle to swoop down and catch it. The sorcerer makes a cow, and Sagburru makes a lion. The wizard makes a goat and a sheep and Sagburru makes a leopard. The sorcerer makes a young gazelle, and Sagburru makes a lion and a tiger. The sorcerer becomes confused and the wise woman tells him that although he does have some powers, he had no sense in trying to enact sorcery in the city that An and Enlil had predestined and that Enlil’s wife, Ninlil, loved so much. The sorcerer pleads ignorance and begs to be allowed to return to Aratta and sing praises of her greatness, but she reminds him that the moon god Nanna had decreed the crime of cutting off milk and butter a capital offense and throws him off the river’s bank into the waters below. Ensuhgirana acknowledged defeat to his “older brother” and Sagburru would go on to become Enmerkar’s bride.

The conflict with Susa does not seem to have been limited to a tournament, however. Gilgamesh’s stepfather, Lugal-Banda is said to have accompanied Enmerkar on a campaign against Elam, but grew sick on the way there to the point where he was reluctantly left behind in a cave by his companions. In the story called Lugal-Banda and the Mountain Cave, or Lugal-Banda and Mount Hurrum, the ill adventurer wakes from a coma and prays to Utu. The sun god “accepts his tears” and sends his twin sister, Inanna, who “envelops him like a woolen garment,” while their father, Suen, helps him by illuminating the cave with the moon. After going through the rations left behind, he begins to hunt and teaches himself to make fire and bake cakes. Another text, called Lugal-Banda and the Anzu bird, or Lugal-Banda and Enmerkar, opens with Lugal-Banda still lost deep within the Zabu mountains. He befriends two giant Anzu birds by sneaking into their nest to feed their chicks celestial cakes and put crowns on the their heads. The Anzu birds, also known as the Imdugud birds or Zu birds, are described as having the teeth of a shark and the claws of an eagle, and were so large that they hunted bulls. Their cry was said to shake the mountains, perhaps representing thunder. The creature is probably the origin of the mythical giant eagle known as the roc in Persian and Arabian lore. Some Sumerian art of an eagle-headed humanoid picking fruit from a tree may be a different depiction of the Anzu bird. Later Babylonian and Assyrian figurines also have similar eagle wings and claws, but a more demonic-looking head. In fact, the image of one of these figurines makes a silhouette appearance in The Exorcist as the demon Pazuzu. For treating their young so well, the Anzu bird offers Lugal-Banda anything he wanted, giving suggestions like a boatload of food and precious metals, the power to shoot never-missing arrows, the courage-giving Lion of Battle helmet, or the milk from Dumuzi’s holy butter churn. But Lugal-Banda chooses to have the ability to run like lightning without ever getting tired. In return, Lugal-Banda offers to have idols carved for him. The Anzu bird agrees as long as he does not reveal his power to his brothers. Lugal-Banda then leaves and catches up with his companions to helps them put Aratta to siege for a year. He uses his new ability to rush back over the seven mountains to Inanna’s temple in Uruk and deliver an important message describing their dire need for assistance. Inanna tells him that if he catches and sacrifices a tamarisk, a freshwater fish, Inanna’s battle strength would be given to the army.

There is probably a third text finishing the trilogy with a story of Aratta‘s defeat, but one has yet to be found. We can assume that Lugal-Banda rose up in rank because of his efforts during the war though, since he would be the one to inherit Enmerkar’s throne, according to the king lists. The first part of his name, Lugal, is Sumerian for king (literally “big man”) and Banda means small, so his name literally means “little big man” or “junior king.” The king listed after “Lugal-Banda the Sherpherd” is not his stepson, Gilgamesh, however, but “Dumuzi the Fisherman,” who rules only 100 or 110 years. This Dumuzi is listed as having lived in the city of Kuara, near Eridu, and is credited with beating Enmebaregesi, the second-to-last king of Kish. Fitting “Dumuzi the Fisherman” into context with Lugal-Banda and Gilgamesh is tough though, especially due to the earlier pre-flood Dumuzi. Most Sumerian texts that focus on Dumuzi involve him interacting with his father Enki, his wife Inanna, and his sister Geshtinanna, but never with any of the other kings from the Uruk dynasty. He is often portrayed in the texts as a shepherd and a king, but not as a fisherman, or for that matter a warrior, and his victory against Enmebaregesi, mentioned in the king lists, is otherwise unknown. Dumuzi is spoken of in the texts of Enmerkar and Lugal-Banda, but these seem to refer only to the god Dumuzi. In on Sumerian text, Gilgamesh presents offerings to Ningishzida and Dumuzi, who seem to be judges of the dead, a somewhat similar role they took as gatekeepers to An in the Myth of Adapa.

Sumerian King List

Pre-Flood Dynasties

1 Alulim ruled 28,000 years in Eridu.

2 Alalgar ruled 36,000 years in Eridu.

1 Enmenluanna ruled 43,200 years in Bad-Tibira.

2 Enmengalana ruled 28,800 years in Bad-Tibira.

3 Dumuzi the Shepherd ruled 36,000 years in Bad-Tibira.

1 Ensipadzidana ruled 28,800 years in Larag.

1 Enmendurana ruled 21,000 years in Zimbir.

1 Ubara-Tutu ruled 18,600 years in Shurrupuk.

2 Ziusudra, his son, rules 36,000 years in Shurrupuk (not present on king lists).

Flood Sweeps Over

First Kish Dynasty

1 Jugur ruled 1,200 years. [First Akkadian King]

…[2 to 12]…

13 Etana the Shepherd ruled 1,500 years. [2800 B.C.]

…[14 to 21]…

22 Enmebaragesi ruled 900 years. “Made Elam submit.”

23 Agga, son of Enmebaragesi, ruled 625 years.

The Kish Dynasty listed as lasting 24,510 years. Maybe 250 years really (2900?-2650?).

First Uruk Dynasty

1 Meshkiagasher, Son of Utu ruled 324 years in E-Anna.

^“Entered the sea and disappeared”

2 Enmerkar, his son, ruled 420 years. He built Uruk up and made Aratta submit.

^“Meshkiagasher’s dynasty ends after 745 years.”

3 Lugal-Banda the Shepherd ruled 1200 years.

4 Dumuzi the Fisherman ruled 100 years.

^“His city was Kuara. He captured Enmebaragesi single-handedly.”

5 Gilgamesh, Lord of Kulaba ruled 126 years. “His father was a Lillu” [spirit? nomad?]

6 Ur-Nungal, his son, ruled 30 years.

The Adventures of Gilgamesh and Enkidu

Gilgamesh was referred to as “Lord of Kulaba,” one of the two districts of Uruk, which means the other half may have been in control of the temple E-Anna. The earliest Sumerian texts actually use the name Bilgames’, but that name became lost in the evolution of the myth, and the majority of people in ancient history knew him as Gilgamesh. He is listed after Dumuzi on the Sumerian King Lists as having ruled Sumer for 126 years, which is small in comparison to some of the earlier cosmic reigns of some of his predecessors that lasted tens of thousands of years. He probably lived some time between 2500 and 2800 B.C, with 2625 being the most precise estimate, based on dating the remains of the Uruk period through a reconstruction of the king lists. Taken literally, the ancient timeline itself would have put the Gilgamesh’s rule closer to 10,000 B.C., but the Sumerian dynasties that were believed by later generations to have lasted thousands of years have been plausibly dated towards more realistic time periods.

Gilgamesh was said to be two parts god and one part man and was conceived by a phantom (or something) while his stepfather Lugal-Banda was adventuring off towards Aratta. Some time in the 100’s A.D., the Greek rhetorician Aelian, wrote in his book, On the Nature of Animals, that Seuechoros, “the king of Babylonia,” who is identified with Enmerkar, had been warned that his virgin daughter would bear a son that would overthrow him. Alarmed, Seuchoros locked his daughter up in his “tower,” which probably refers to a ziggurat. She was impregnated by “some obscure man,” the Greek term literally meaning “invisible.” The vagueness of the concept seems to match the one expressed in the Sumerian king list, which says his father was a Lillu, a word that has been translated as “phantom” or “nomad.” In Aelian’s story, when Gilgamesh was born, he was flung from the tower, but an eagle saved him and brought him to a gardener to raise. Although none of the ancient Gilgamesh tales speak of this miraculous event, there is a similar Akkadian story that tells of how the later king Sharru-Kin (or Sargon) was saved despite being thrown into a river, and that he too was raised by a gardener.

Gilgamesh’s adventures were written in several episodes which were later combined, edited, and translated into the Epic of Gilgamesh, the first multi-chaptered story. The least mythical-sounding of the Gilgamesh episodes is Gilgamesh and Agga, in which Gilgamesh, the Lord of Kulaba, and his slave/best friend Enkidu defend their city against the son of Enmebaregesi. Agga tortures one of Gilgamesh’s men until he actually sees Gilgamesh in battle, at which point a peace deal is quickly struck. Gilgamesh praises Agga as his “overseer” and “lieutenant,” while the people of Uruk dub Gilgamesh “the great Rampart of An.”

Another story tells of Gilgamesh going off to a mystical land with Enkidu in order to vanquish a monster named Huwawa (also translated Humbaba). There are two versions of the Sumerian episode, Gilgamesh and Huwawa, in which Gilgamesh and Enkidu take 50 men and travel to “the Land of the Living,” a land of cedar trees. Gilgamesh falls asleep, either due to exhaustion or by Huwawa’s “terrors,” but Enkidu wakes him with some ointment. Enkidu tries to get Gilgamesh to leave, but Gilgamesh convinces Enkidu to keep his courage up, telling him, “two people together will not perish! A grappling-poled boat does not sink! No one can cut through a three-ply cloth!” Gilgamesh then finds Huwawa and strikes a false alliance with him, offering his sister, Enmebaragesi, as a concubine. This opens up the possibility that the second-to-last king of Kish was in fact a woman and that she became one of Gilgamesh’s concubines after Dumuzi the Fisherman defeated her. Gilgamesh is able to trade food and supplies for each of the monster’s seven terrors. Just as Gilgamesh was to kiss Huwawa to seal the deal, he punches him instead, and then ties him up. Huwawa insults Gilgamesh for his deceit, and the Lord of Kulaba considers letting him go, but Enkidu fears it will only bring Gilgamesh’s death, so one or both of them cut Huwawa’s throat. When the two adventurers return, Gilgamesh finds that Enlil is angry at him for killing the guardian of the cedar forest. Enlil takes Huwawa’s terrors and spreads them out amongst the fields, the rivers, the reed-beds, the lions, the palace, and to Nungal, goddess of prisoners.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu slaying Huwawa (?)

In Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, Gilgamesh comes into conflict with Inanna when he tries to “dispense justice” at E-Anna. He tells her that he will not take over her portion in the temple, but warns her not to block his way either. Inanna then goes to An, who seems to be her father in this story, and asks for the Bull of Heaven. When he refuses, she threatens to scream so loud that all heaven and earth would hear. Afraid, An gives her the bull, and she sets it on Uruk. The bull devours the land bare, drinking the water, and muddying what was left with giant cowpats. Gilgamesh and Enkidu are called from a bar to fight it; Enkidu grabs it’s tail and Gilgamesh cuts it’s head off with his giant axe, and the blood splatters like rain, harvesting the crop. In a version found in Me-Turan, Gilgamesh cuts up the bull and throws a piece of meat in Inanna’s face, causing her to flee “like a pigeon.” Standing by the bull’s head, Gilgamesh then weeps bitter tears, asking himself, “Just as I destroyed you, shall I do the same to her?” He divides the meat of the bull among the people of the city and apparently forgives Inanna, making the horns into oil flasks for her at the E-Anna ziggurat. The story may reflect a mythologized chronicle of Gilgamesh conquering the E-Anna district and a subsequent natural disaster such as a hurricane or tornado, symbolized by the bull.

Enkidu and Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven (?)

The most surreal episode of the warrior dual is Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld. It begins with a short creation story:

“In those days, in those distant days, in those nights, in those remote nights, in those years, in those distant years; in days of yore, when the necessary things had been brought into manifest existence, in days of yore, when the necessary things had been for the first time properly cared for, when bread had been tasted for the first time in the shrines of the Land, when the ovens of the Land had been made to work, when the heavens had been separated from the earth, when the earth had been encircled by the heavens, when the name of mankind was fixed, when An had taken the heavens for himself, when Enlil had taken the earth for himself, when the netherworld had been given to Ereshkigal as a gift; when he set sail, when he set sail, when the father set sail for the netherworld, when Enki set sail for the netherworld…”

The story proceeds to tell how the South Wind uprooted a huluppu tree (perhaps a willow?) from the Euphrates river, which Enlil tells Inanna to replant in her garden. Inanna waters the tree with her feet, hoping to make a nice chair and bed out of it. But then a “snake that could not be charmed,” an Anzu bird, and a female wind demon called the Lilutu all infested her tree. Inanna’s twin brother Utu refuses to help her, so she calls her “brother,” Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh takes his giant bronze axe and kills the snake with it, then chases off the Anzu bird family and the Lilitu. He then chops up the tree and uses the wood to build a bed and a chair for Inanna, which probably represents Gilgamesh building a temple for her.

Gilgamesh uses the wood from the tree to create two objects, a pikku and a mukku. Although it’s unknown what they are, they’re generally assumed to be a drum and a drumstick. Gilgamesh continuously plays the pikku and mukku in the main square, praising his abilities, but then the complaints of the widows and young women of the city cause his pikku and mukku to fall into the netherworld. He tries to reach for the instruments with his hands and feer, but couldn’t grasp them. This causes him to cry bitterly, saying that he would treat the carpenter’s wife and child like his own mother or sister. This may represent Gilgamesh being able to “drum up” popular support by building extensions for Inanna’s temple, but ultimately losing it, either by creating widows due to constant warfare or by “taking all the women for himself,” as the Epic of Gilgamesh suggests. Enkidu offers to go down to retrieve them, and so Gilgamesh warns him to obey all the rules of the netherworld when he is there: no clean garments, no ointment, no spear throwing, no shoes, no shouting, and no kissing the child you love while hitting the wife or child you hate. But Enkidu didn’t listen and was caught doing all those things, and gets trapped in the land of the dead.

Enlil refuses to help Gilgamesh bring Enkidu back, but Enki had Utu open a hole into the netherworld for him and brought Enkidu out. The two hugged and kissed and Gilgamesh asked Enkidu what the netherworld was like. Enkidu told him to sit down because the order of the netherworld was going to make him weep. Those who had only one or two sons were the worst off. Those who had increasingly more sons were increasingly happier, while the one who has seven sons was allowed to be a companion of the gods and sit on a throne to give judgments in the afterlife. The palace eunuch was propped in the corner and the woman who never gave birth was thrown away like a broken pot. The man who never undressed his wife works on a never-ending rope. Those that were eaten by a lion still felt the pain in their hands and legs and the diseased man was eaten by worms. The man who fell in battle still did not have his mother or father to hold his hand and his wife still wept for him. The man who had no funerary offerings of food was forced to eat the bread crumbs tossed out on the street. Stillborn children, however, played on a table of gold and silver, laden with honey, and the ones who died in their sleep now lied on the bed of the gods. However, the ones Enkidu did not see were those who had been burned alive, because their spirit had gone up into the sky along with the smoke. Another version of the story found in Ur says that the citizens of Sumer and Akkad drink muddy water. Gilgamesh asks about his parents and Enkidu tells him that his parents drink muddy water as well. Another text from Ur says that Gilgamesh left Enkidu and returned to the city, outfitted himself with weapons, and declared to the sun god Utu as he came from his bedchambers that his parents would drink clean water again. He and the people of Uruk weep for nine days and then repulse the people from the city of Girsu, achieving a better afterlife for his parents. Another version from Me-Turan end saying, “His heart was smitten, his insides were ravaged. The king began to search for life. Now the lord once decided to set off for the mountain where the man lives.” This seems to be the foreshadow another adventure coming from the Epic of Gilgamesh in which he meets the Sumerian Noah.

To the Sumerians, the Lilitu which were said to have infested Inanna’s tree caused sexual dysfunction and complications in pregnancies. They had a male equivalent named the Lilu, and were believed to have inhabited desert wastelands. Both were seen as faceless sex demons who rendered their victims helpless by preying on their dreams. The same creature, Lilith, appears in the Jewish Talmud and Midrash as a female sex demon who would defile men’s purity in their sleep. In late medieval Jewish lore, she was considered to be the first wife of Adam, who was cursed by God to slay 100 children-- if not human ones then her own-- every night because she would not have sex with Adam in a submissive posture. Because of this very chauvinistic tale, Lilith is now a feminist icon as well as a music fair. In Jewish lore, Lilith’s brood was called the Lilum, and they were believed to perpetuate madness and barrenness in women. The concept of Lilith as sex demon may also have been an inspiration behind the demonic succubus of Christian lore. The Book of Isaiah uses the Lilith in describing the desolation that Yahweh will bring on Edom, who as described in the 34th chapter, is “angry with all nations.” After Edom is made into a blazing pitch of burning sulfur, the Lilit is said to settle and make a home there, just as she did in the haluppu tree (34:14). The Greek Septuagint translates the word Lilit into “satyr,” one of the mythological goat-legged companions of Dionysus, often depicted in Greek art with an erection. The King James Version translates the same word, without precedent, into “screech owl,” while the New International Version uses the phrase “night creatures.” There is also a passing reference to Lilith in the Dead Sea Scroll known as “Song of the Sage,” in which the instructor proclaims God’s splendor in order to frighten away various evil spirits, including Lilith.

The Lamia of Greek mythology is another mythological creature that bears a remarkable resemblance to Lilith. Like the lilitu, they had a sexual appetite for men and killed children. Lamia was said to have been the beautiful queen of Libya, the western neighbor of Egypt. She was born from the goddess Libya and the god Belus, whose name is derived from the Middle Eastern title, “Ba’al.” Lamia became the lover of Zeus, which caused Zeus’ wife Hera to kill off all her children and turn her legs into a snake’s tail. She was cursed with the memory of her dying children and would eat human children because she couldn’t bear to see a happy mother with her children. Like Lilith, she gave birth to a brood of evil spirits, half-serpentine bloodsuckers with claws and hooves called lamiae. Being by a lamia could only be cured by the sound of a lamia's roar.

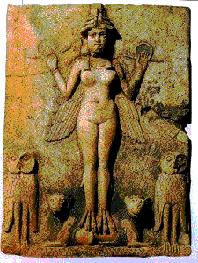

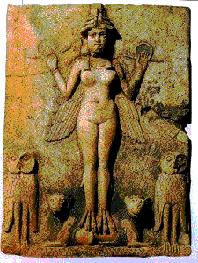

There is a Sumerian or Assyrian relief dated to 1950 B.C. of an owl-woman that is popularly identified with Lilith, although most scholars instead identify the figure with Inanna or her netherworld sister, Ereshkigal. The stone slab, called the Burney Relief, depicts a partially nude woman with wings, snake hair, and owl’s feet, holding what appear to be trumpets and standing on two lions and flanked by two owls. There has been questions as to whether the identification with Lilith has been influenced by the “screech owl” translation in the King James Version, yet the popularly-made identification seems more valid than the scholarly ones. Inanna is often depicted with lions, but never with owl feet, and only in the earliest of Sumerian depictions does she have wings. There is also no reason to believe the Queen of the netherworld was associated with owls or even the night. The name Lilitu is believed to be rooted either in the Sumerian lil, meaning wind, which would connect it to birds and flight, or the Proto-Semitic lyl, meaning night, emphasizing it‘s nocturnal nature, which would also have a natural association with the owl.

The Burney Relief, possibly a Lilitu, Ereshkigal, or Inanna; dated 1950 B.C.

Gilgamesh dies after being bedridden for six days in the badly damaged Death of Gilgamesh text. He arrives at the assembly of the gods and they go over the major events of his life: fetching the cedar tree, killing Huwawa, setting up monuments for future generations, setting up temples to the gods, and having reached Ziusudra. This reference to the Sumerian Noah is especially puzzling. Although both versions of Gilgamesh and Huwawa have a few lines of the story missing due to damage, neither of them make any mention of Gilgamesh setting up these temples or meeting Ziusudra. But if Gilgamesh had met Ziusudra while in the “Land of the Living,” it would strengthen Kramer’s identification of the Land of the Living with Dilmun. The later Babylonians also called the home of their gods the “Land of the Living,” so it’s possible that there is another version of the Gilgamesh and Huwawa text that has Gilgamesh meet Ziusudra. But if “the man on the mountain,” in Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld is also a reference to Noah, as the Epic of Gilgamesh suggests, it would not fall in continuity because that would mean Enkidu would have had to have died before Gilgamesh went there. Another problem is that the Epic of Gilgamesh has Gilgamesh travel to the “Land of Cedar” to fight Huwawa first, and then to the Island of Dilmun only after Enkidu dies. This would mean that the later editor of this epic either didn’t recognize the “Land of the Living” as Dilmun, or decided to change the details to better fit his version of the story. It may be that there were two competing traditions of Gilgamesh traveling to the land of the gods, one with Enkidu and one after Enkidu dies, and that the two traditions were combined in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

After going over Gilgamesh’s deeds in the Land of the Living, the gods speak of how he brought divine powers of forgotten lore to Sumer and correctly carried out the rites of hand and mouth washing. Enlil and Enki speak to each other and then Enki asks An to make an exception to the promise he made that no one after would be given immortality. An instead decides that Gilgamesh should become one of the judges of the netherworld, so that his word would be as important as that of Ningishzida or Dumuzi. Even though he is said to be now counted among the Anunnaki, Gilgamesh is still depressed at losing immortality. The gods tell him that he “must have been told this is what the cutting of the umbilical cord involved” and that he should not go to the netherworld “with a heart knotted in anger.” He shouldn’t be depressed because his family, the city elders, and his friend Enkidu would soon be joining him. The floodgates of the Euphrates are said to have been diverted so that his tomb could be made in the river bed. His favorite wife, junior wife, children, beloved musician, cup-bearer, beloved barber, and his beloved retainers are then said to have “laid down in their places,” with another mention of what may be a “purified” palace. Gilgamesh sets out gifts for Dumuzi, Ereshkigal, and Ereshkigal’s vizier and messenger, the fate-cutter Namtar. Gilgamesh is reminded that Enlil gives people offspring so that they will make funerary statues in order that their names not be forgotten and sink into oblivion, and the story ends with praises to Ereshkigal.

As the story suggests, there is archaeological evidence that Sumerian attendants would often commit mass suicide in order to join their king, queen, or nobleman in the afterlife. A tomb holding 59 bodies was excavated from the Sumerian city of Ur by the famous British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1929. The skeletons were still holding the cups of poison they had drank to join a queen or noblewoman named Pu-Abi, who wore golden jewelry and semi-precious stones. The remains were kept in the Baghdad museum until they were destroyed during the Iraq war. However, many of the artifacts from the tomb survived, such as a 4,500-year-old lyre and a board game with game mechanics similar to Parchesi. I was able to see the surviving relics while they were on a museum tour at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in 2006 and was amazed by how incredibly small and intricate the links in the golden necklaces and bracelets were for such ancient pieces of jewelry.

In 2003, a German-led expedition discovered what is believed to be the underwater tomb of Gilgamesh, including where the Euphrates once flowed over it. Jorg Fassinbinder of the Bavarian department of Historical Monuments in Munich did not want to “say definitely that it was the grave of King Gilgamesh, but it looks very similar to that described in the epic.” Garden structures, field structures, and Babylonian houses were among some of the findings at the site. Also found was a very sophisticated canal system, which Fassinbinder described as being like “Venice in the desert.”

The Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is generally believed to be the first frame narrative, that is, a story made up of shorter stories. It consists of a combination of Gilgamesh and Huwawa and Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, with the second half of Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld attached to the end as what many scholars consider to be an appendix. It is written in the Akkadian language and is made up of 12 tablets, the 12th being the “appendix.” However, the epic tale was not just an amalgamation of the Sumerian tales, but a greatly expanded elaboration that presents human emotion and character development unlike anything that had been accomplished beforehand. It’s believed to have been compiled by Sin-Leqi-Unninni, a scribe from Uruk from around 1300 B.C. The Epic of Giglamesh gives us the premier model for some of the greatest epics of all time: the Illiad and Odyssey, the Hercules tales, Beowulf, the Arthurian legends, and the German epic Nibelungenlied. The most complete version found comes from the famed Assyrian library of King Ashurbanipal, who reigned in the mid-600’s B.C. It starts off with the following prologue, mentioning Gilgamesh‘s meeting with Ziusudra, who in this epic is called Utnapishtim, meaning “The Far-Away”:

“Fame haunts the man who visits the underworld, who lives to tell my entire tale identically. So like a sage, a trickster or saint, GILGAMESH was a hero who knew secrets and saw forbidden places, who could even speak of the time before the Flood because he lived so long, learned much, and spoke his life to those who first cut into clay his bird-like words. He commanded walls for Uruk and for E-Anna, our holy ground, walls that you can see still; walls where weep the weary widows of dead soldiers. Go to them and touch their immovable presence with gentle fingers to find yourself. No one else ever built such walls. Climb Uruk’s Tower and walk about on a windy night. Look. Touch. Taste. Sense. What force created such mass?

“Open up the special box that's hidden in the wall and read aloud the story of Gilgamesh’s life. Learn what sorrow taught him; learn of those he overcame by wit or force or fear as he, a town’s best child, acted nobly in the way one should lead and acted wisely too as one who sought no fame. Child of Lugalbanda’s wife and some great force, Gilgamesh is a fate alive, the finest babe of Ninsun, she who never let a man touch her, indeed so sure and heavenly, so without fault. He knew the secret paths that reached the eagle’s nest above the mountain and and knew too how just to drop a well into the chilly earth. He sailed the sea to where Shamash [Utu] comes, explored the world, sought life, and came at last to Utnapishtim [Ziusudra] far away who did bring back to life the flooded earth. Is there anywhere a greater king who can say, as Gilgamesh may, ‘I am supreme?’”

The epic begins telling how Gilgamesh was abusing his authority as king and how his tribe was “invincible” and “aroused by small insults.” He also kept his warriors away from their fathers and also took advantage of his kingly right to sleep with the bridesmaids of the city before the groom. The men of Uruk prayed to heaven, asking, “Who created this beast with an unmatched strength and a chant that fosters armies? This warrior keeps boys from fathers in the day. Is this Gilgamesh, is this the shepherd of Uruk’s flocks, our strength, our light, our reason, who hoards the wives of other men for his own purpose?”

Anu, the god of heaven, tells the earth goddess Aruru that since she is the one that fashioned man, she should make an imitation of Gilgamesh so that they would “engage, then disengage, and finally let Uruk’s children live in peace.” She created Enkidu out of a rock in the image of the war god Ninurta and then throws him in the forest. Enkidu becomes a Wildman, running with animals and eating grass. After he begins releasing animals from the traps of the hunter, the hunter’s son is sent to Uruk to bring a courtesan back in order to domesticate him. Gilgamesh sends Shemhet, a temple priestess of Ishtar, and the priestess has sex with Enkidu for a week. “Hot and swollen first, she jumped him fast, knocking out his rapid breath with thrust after loving thrust. She let him see what force a woman has, and he stayed within her scented bush for seven nights, leaping, seeping, weeping, and sleeping there.” After this, Enkidu tries to return to the beasts but they run away from him now. Shemhet tells him, “Now you are a god, with no more need of dumb beasts, however fair. We can now ascend the road to Uruk’s place, where Anu and Ishtar dwell, and there we will see Gilgamesh, the powerful, who rides over the herd like any great king.” And at her words, he wished for a friend for the first time, then asked Shemhet to go with him and be his love at the “immaculate domicile.” He tells her he can do whatever he wants with his “mountainous power” and that he could promote her fame. She then warns him to fear his anger because Gilgamesh is blessed by the gods, but also seems to entice him, and then predicts that Gilgamesh will have a dream foreseeing Enkidu’s arrival. Gilgamesh in fact has two dreams, one in which Enkidu is a “rising star” and one in which he is an “axe,” and in both of them, Gilgamesh sees himself embracing the form, like a “woman he loves best.”

Along the way to Uruk, Shemhat disguises themselves as poor travelers, and they stay with shepherds as Enkidu learns his “new human ways,” including: tracking sheep, using weapons to fight the beasts attacking the herds, how to eat and drink as humans do, and the customs of the city. He also learns of Gilgamesh’s harsh rule, and even before he gets there, he is surrounded by an entourage of people who want to see Enkidu take down the unfair king. Enkidu first meets Gilgamesh at the gate of the city where lovers’ go, where Gilgamesh is bringing some of his new female companions. The two fight for hours along the walls of Uruk, as they were meant to do, but then Enkidu finally sues for peace, saying he had come to “match some fate” with him, not destroy him, and the two joined in sacred friendship.

In tablet three, Gilgamesh convinces Enkidu to go with him to kill the monster Humbaba against the wishes of Gilgamesh’s mother, Ninsun. Ninsun calls out to Shamash, asking why he “shaped his mind” to go after the monster. Enkidu is afraid, but Gilgamesh tells him, “Only gods live forever with Shamash, my friend; for even our longest days are numbered. Why worry about being dust in the wind? Leap up for this great threat. Even if we were to fail and fall in combat, all future clans would say I did the job.” As they leave, the people of Uruk tell Gilgamesh to let Enkidu lead the way and take the risks for him, since he knew the forest well and knew what fights to pick. When fighting some of Humbaba’s guards, Enkidu’s hand is crushed by a shutting gate. Enkidu cries out to Gilgamesh asking what he should do, and Gilgamesh replies, “Brothers, as a man in tears would, you transcend all the rest who’ve gathered, for you can cry and kill with equal force. Hold my hand in yours, and we will not fear what hands like ours can do. Scream in unison, we will ascend to death or love, to say in song what we shall do. Our cry will shoot afar so this new weakness, awful doubt, will pass through you. Stay, brother, let us ascend as one.”

Following Humbaba’s path, they come to the “home of the gods,” the paradise of Ishtar’s other self, called Irnini-most-attractive. All beauty true is ever there where gods do well, where there is cool shade and harmony and sweet-odored food to match the mood.” Gilgamesh has a dream, and this time it is Enkidu who urges him on, telling him that it is a sign from Shamash that they would triumph. Then, without any description of how, Gilgamesh and Enkidu defeat Humbaba, and the dying beast calls out for mercy, saying they could take all the lumber they wanted. But Enkidu shouts even louder, saying, “Kill the beast now, Gilgamesh. Show no weak or silly mercy toward so sly a foe.” In one version of the story, Humbaba calls Enkidu “son of a fish, who knew not his father… who never sucked the milk of his mother?” This might be an association with the fish cult that Enki and Adapa represented. It also seems to insinuate that Enkidu was born of one of the “virgin” priestesses without a father. Gilgamesh slays Humbaba, splattering blood on his cloak and sandals. The chapter then ends, saying, “Soiled by this violent conflict, the friends began their journey back to Uruk’s towering walls expecting now to be received as heroes who had fought and won a legendary battle.”

In tablet six, Ishtar comes down to Gilgamesh while he is bathing and asks him to marry her and come to her home “where holy faces wash your feet with tears as do the priests and priestesses of Anu,” and that if he did, everything he touched would turn to gold, the same wish given to King Midas by Dionysus. Gilgamesh asks, “So how am I to love you as you want but still be free to roam or run at will? If we tickled and teased and giggled and kissed, we’d have no time to think clearly of all the things non-lovers do who spend their time better than those who play all day in bed. Besides, I hardly know or trust you very much.” Gilgamesh then recites a song he made for her in which he makes a very short mention of Dumuzi, who in the Akkadian language is called Tammuz:

Ishtar is the hearth gone cold,

A broken door that cannot hold,

A fort that shuts its soldiers out,

A commandant who’ll only pout;

Tar that can’t be washed away,

A broken cup, stained and gray;

And worse than that or even this,

A god’s own sandal filled with piss.

She’s rock that’s soft and useless.

She’s fruit that’s dry and juiceless.’

You’ve had your share of boys, that’s true,

But which of them came twice for you?

Let me list the ones whose lives you blew:

First was Tammuz, the virgin boy you took,

after a three-year-long seductive look.

Then you lusted for a fancy, colored bird,

and cut its wing so it could not herd.

Thus in the lovely woods at night,

The bird sings, ‘I’m blind. I have no sight.’

You trapped a lion, too, back then.

Its cock went in your form-as-hen.

And then you dug him seven holes

in which to fall on sharpened poles.

You let a horse in your back door

By lying on a stable floor;

But then you built the world’s first chain

To choke his throat and end his reign.

You let him run with all his might

As lovers sometimes do at night

Before you harnessed his brute force

With labor mean, a cruel divorce.

So did his mother weep and wail

To see his hoof set with a nail.

Gilgamesh sings on, telling of two other victims: a shepherd boy and a plowman named Ishullanu, who “trimmed her father’s trees.” After hearing all of this, Ishtar goes to her father Anu and cries, “Daddy, daddy, pleeeeease, Gilgamesh called me a tease!” Anu asks her if she started it, but Ishtar demands that he unleash the Bull of Heaven on him or else she would wreck havoc. Anu warns that it will lead to years of famine, but Ishtar tells him that she has seen to those that she loved. Gilgamesh’s refusal to marry Ishtar and the subsequent famine may reflect the belief that Ishtar’s Sacred Marriage ceremony was intended to ensure a fertile year. If Gilgamesh had refused to participate in such a ceremony before a natural disaster hit, it would no doubt have been blamed on him. When the Bull of Heaven attacks, Enkidu shouts encouragement to Gilgamesh and grabs the bull. Gilgamesh then bull-dances around it and stabs it in the neck with a sword before tearing out it’s heart and offering it to Shamash. Ishtar appears on Uruk’s wall, wailing like a widow, and Gilgamesh throws a hunk of meat in her face, just as before. He fills the horns with 6 jars of oil, but brings it to the altar of his stepfather Lugalbanda rather than Ishtar, and then has them enshrined. The two wash the blood off in the forgiving river of the Euphrates and then party all night long.

In tablet seven, Enkidu tells Gilgamesh about a dream he has in which the gods discuss which one of them should be held guilty for the death of the Bull of Heaven. Although Shamash intervenes for them, saying that they slew Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven with his consent, the others want revenge. Enkidu soon grows sick, and begins to blame the 200-foot gate that crushed his hand during his adventure to Humbaba’s forest, which he says was crafted on the holy ground of Nippur, Enlil’s city. If the Cedar Forest was in Elam, then this gate may have been the been the “limit of Shamash” that provided the border between Akkad and Elam. Enkidu begins cursing the hunter who first found him and his former lover Shemhet, but Shamash comes to him and tells him if she hadn’t of brought him to Uruk, he never would have met Gilgamesh and have become famous. Shamash tells him how Gilgamesh will show Uruk how to mourn for Enkidu as well, and then go mad with grief, which makes Enkidu speechless and resolved to death. Enkidu then has a vision of the dark prison that awaits him and makes a final regret that he was robbed of his warrior’s destiny to die in battle.

In tablet eight, Gilgamesh leads Uruk in mourning and sets Enkidu’s body on a pedestal. In tablet nine, he decides to venture to the island of Dilmun to learn the secret of eternal life from the ark builder, Utnapishtim, in what can be called the proto-typical ‘journey to the wise man on the mountain.’ Just like in the Eridu Genesis, Utnapishtim is the only mortal to have been bestowed with immortality, and he is allowed to stay on the virgin island of Dilmun for all time. Gilgamesh fights lions and scorpion men until he reaches the Mountain of Mashu, where he speaks to one of the scorpion guardians. Although amazed that Gilgamesh had traveled further than any human before him, the guardian warned Gilgamesh that the land past him was dark and frozen. In tablet ten, Gilgamesh meets a woman named Siduri at the sea. Although she is afraid of Gilgamesh at first because of his haggard looks, she lets him in and gives him a drink that refreshes his soul. Gilgamesh asks her for help crossing the sea to Dilmun, but she tells him that only the sun god Shamash dared to venture there, and she tries to dissuade him from his quest:

“Remember, mighty king, that gods decreed the fates of all many years ago. They alone are let to be eternal, while we frail humans die as you yourself must some day do. What is best for us to do is to sing and dance. Relish warm food and cool drinks. Cherish children to whom your love gives life. Bathe easily in sweet, refreshing waters. Play joyfully with your chosen wife. It is the will of the gods for you to smile on simple pleasure in the leisure time of your short days.”

Gilgamesh then moves on, cutting through the forest until he reaches Utnapishtim’s ferryman, Urshanibi. Gilgamesh tells him his story but the ferryman makes him do penance for destroying idols and touching holy stones. After chopping down several trees and preparing them for the ferryman, Urshanibi grudgingly takes Gilgamesh across to Utnapishtim. Gilgamesh hails the Sumerian Noah as a legendary god and tells him how he traveled without rest, cursed and rejected, in order to meet him. Utnapishtim tells him, “Why cry over your fate and nature? Chance has fathered you. Your conception was an accidental combination of the divine and mortal. I do not presume to know how to help the likes of you.” He goes on to tell Gilgamesh that although no one has ever seen Death, it is real. Only Shamash knows how many more people will die from conflicts and natural disasters. “Somewhere above us, where the goddess Mammetum decides all things, Mother Chance sits with the Annunaki and there she settles all decrees of fable and of fortune. There they issue lengths of lives; then they issue times of death. But the last matter is always veiled from human beings. The length of lives can only be guessed.”

In tablet eleven, Gilgamesh praises Utnapishtim as a warrior who preferred peace and asks Utnapishtim how he might ascend to become one with the gods. Utnapishtim tells him that only he would dare ask such a question, but that he would tell him a story no one had heard. He tells how the gods met in Shurrupuk and decided to flood the land and how Ea (that is, Enki) warned him to forsake wealth and build the ark. Utnapishtim asks what he should tell everyone else and Ea says to tell them that Enlil hates them. He builds the ark in a week, and then the sky storms for another week, and even the gods cry at it’s destructive power. Tears flow down Utnapishtim’s face as he opened a hole in the ark and saw the morning sun. The waters recede for another week and the ark comes to rest on Mount Nimush. Utnapishtim performs a sacrifice and the sweet smell gathers the gods in flight above him in apparitions. Aruru, the earth goddess who created man and Enkidu, blames the flood on Enlil and tells the gods not to allow him any of the food. Enlil is outraged that Utnapishtim lives, but Ninurta reminds him that only Ea can create speech, and Ea himself tells Enlil:

“Sly god, sky darkener, and tough fighter, how dare you drown so many people without consulting me? Why not just kill the one who offended you, drown only the guilty? Keep his life cord; harness his destiny. Rather than killing rains, set cats at people’s throats. Rather than killing rains, set starvation on dry, parched throats. Rather than killing rains, set sickness on the minds and heads of people. I was not the one who revealed our god-awful secrets. Blame Utnapishtim, who sees everything, and knows everything.”

Utnapishtim tells how Enlil then came down and raised him and his wife from the slime and deified them, sending them to “rule the place where rivers start,” matching the description given in Genesis in which “A river watering the garden flowed from Eden; from which it was separated into four headwaters.” (2:10). This flood story found in the Epic of Gilgamesh is also the one that most resembles the hybrid one redacted in Genesis. Unlike the earlier versions, animals are also brought on the ark, confirming that the conception is that of a world flood instead of a localized one. Also like the Bible version, Utnapishtim sends out three different birds to test the waters just as Noah did.

It’s often said that the flood story in the Bible is superior to the earlier pagan versions because it introduces a moral element to an otherwise senseless act of the gods. While the Epic of Atra-Hasis implies that Enlil caused the flood because he couldn’t sleep, the Epic of Gilgamesh says that Enlil “hated” the people, presumably because of their bad actions. Whether one or the other is better is relative to one’s own value system. In modern times, adding a moral meaning to a disaster is usually taken as sign of disrespect towards it’s victims. For example, there have been some attempts by some religious thinkers to interpret the 9/11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina as divine retribution, but these ideas have been met with a lot of verbal backlash. Attributing the death of not only the guilty but also the innocent, even babies, to a vengeful god is not a comforting thought for many people. This seems to include many ancient people, reflected by Enki’s scolding of Enlil. Although certainly foreign to our own moral conceptions, the Epic of Gilgamesh nevertheless portrays Utnapishtim as being praised for being a peaceful warrior. Gilgamesh is ridiculed for destroying idols, while many parts of the Old Testament advocate murder and the destruction of idols on the grounds of religious intolerance. Certainly the Greek version of the flood contains an ethical message against cannibalism and human sacrifice. It’s also possible that there are allusions in the earlier versions of the flood story to a “moral” reason for the flood that has been lost in translation. Ostensibly, the flood is attributed to the people creating a “noise” that Enlil does not like, but is not explained in adequate detail. This may have been meant to be taken literally, that the actual sound of so many people talking some how bothered him, or it could possibly refer to cries of injustice, similar to how God “hears” the blood of Abel crying to him from the ground in Genesis (4:10).

After the flood story, Utnapishtim then tells Gilgamesh to reflect on the story and consider which gods will be called on the direct his path and future life. He asks that Gilgamesh stay awake with the stars and pray for an entire week, but Gilgamesh quickly falls asleep the first night. Utnapishtim bakes bread every day for Gilgamesh as he sleeps, and after he awakens from a death-like sleep, there are six loaves. Seeing that he failed, Gilgamesh says, “Help me, Utnapishtim. Where is home for one like me whose self has been robbed of life? My own bed is where death sleeps and I crack her spine on every line where my foot falls.” Utnapishtim calls for his ferry man and asks him to take Gilgamesh to the freshwater pools to clean his wounds, tie up his hair, and give him a sacred cloak.

Gilgamesh then returns and Utnapishtim’s wife convinces her husband to reward him for the long journey he took to find him. So Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh of a plant of eternal life which has stinging thistles and hides in the rocks and thrusts itself deep into the ground. Gilgamesh goes out in search for it and decides to explore the bottom a freezing cold pool of water by jumping in with weights. The weights take him to bottom of the pool quickly, where he sees the plant and grabs it. The thistles sting him and the plant holds fast the ground, but Gilgamesh is able to pull it out and then throw off the weights to swim back to the surface. Gilgamesh is ecstatic and boasts that he is going to let all the aged men of Uruk eat some of it, so that they all could be forever young. But after setting up camp, Gilgamesh bathed himself in a pool and a snake came by and ate the plant. He sees the snake turn young and then begins to weep, saying, “Why do I bother working for nothing? Who even notices what I do? I don’t value what I did and now only the snake won eternal life. In minutes, swift currents will lose forever that special sign that god had left me.” Urshanabi takes him back home to Uruk, and as they arrive, Gilgamesh tells the boatman, “Rise up now, Urshanabi, and examine Uruk’s wall. Study the base, the brick, the old design. Is it permanent as can be? Does it look like wisdom designed it? The house of Isthar in Uruk is divided into three parts: the town itself, the palm grove, and the prairie.” In one version of the story, Gilgamesh tells Urshanabi that the city’s walls were built by the Seven Sages.

The theme of a snake stealing eternal life is another parallel that can be found in the Garden of Eden story. In this story, the snake eating the plant of eternal life and “turning young” is probably a reference to the snake’s ability to shed it’s skin, thus taking on a new “younger” body. In Genesis, God punishes the snake for deceiving Eve by taking away his legs and making him crawl in the dust on it’s belly. Vestigial limbs in the form of nub-like legs on primitive snakes like the python and boa constrictor prove that snakes did in fact have legs at one time, but lost them in the evolutionary process millions of years ago. In differing ways, both stories combine an explanation for the mortality of humankind with why the snake is unique among animals.

As mentioned earlier, the twelfth tablet is usually seen as an appendix, with the general consensus that it was added to the story at a later date. It begins half way through Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld with Gilgamesh lamenting the loss of his drum, without any back story as to how he built it out of Inanna’s haluppu tree and lost it due to the complaints of Uruk’s citizens. Enkidu suddenly reappears without explanation as well, volunteering to descend into the netherworld to get the drum. Gilgamesh gives Enkidu the rules of the Netherworld in rhyming form, at the end saying, “Around you, Enkidu, the lament of the dead will whirl and scream, for she [Ereshkigal] alone, in that good place, is at home who, having given birth to beauty, has watched that beauty die. No graceful robe any longer graces her naked self and her kind breasts, once warm with milk, have turned into bowls of cold stone.” Again, Enkidu ignores Gilgamesh’s advice and wears bright clothes and makeup, takes weapons with him, and mocks the dead. He went clothed before the naked, ate in front of the starving, and danced before the grieving, kissed a girl, struck a woman, enjoyed his fatherhood, and fought with his son. Enlil and the moon god Suen ignore Gilgamesh’s pleas to bring Enkidu back, but Ea decides to order Nergal to free him. In other mythological texts, Nergal is said to have pulled Ereshkigal off her throne by her hair to become king of the netherworld, but in this story, he is a soldier who “is accustomed to absurd orders.” Nergal brings Gilgamesh half way down and Enkidu half way up, and the two meet between the surface and the netherworld. Reluctantly, Enkidu tells Gilgamesh what the netherworld is like: how the man who never fathered children was a “no-man who died,” how the man who fathered only one son sat sobbing in a field, and how men with more and more sons are happier and happier. Those who died too soon sit on a couch sipping water and those who died in war still have relatives who weep for him. Homeless nomads are still wandering restlessly and those who are not given food at their graves must scrounge for it in dumps. The story then abruptly ends.

Their Secret Identities

The description of Enkidu has prompted some readers to question the meaning behind his status as a “wild man.” Did this mean that he was a wandering nomad? Could he have been another race or species of man, like a Sasquatch or Neanderthal? Unless the depiction of Enkidu eating grass is meant as hyperbole, his stomach must have been more adapted to eating like apes and monkeys do. Might the monster Grendel from the Epic of Beowulf be another example of cross-racial or cross-species exaggeration? Another possibility is that Enkidu simply represented another, more earth-bound culture. If it was a priestess of Inanna/Ishtar who brought Enkidu to fight Gilgamesh in Uruk, is it possible that the story might be the symbolic representation of a rival king backed by the E-Anna temple to take Gilgamesh’s throne? Enkidu is called the “son of a fish,” which matches the title of the king who ruled before Gilgamesh, Dumuzi the Fisherman. While Dumuzi the Fisherman is recorded as defeating Enmebaragesi, Enkidu is said to have fought Enmebaragesi’s son Agga with Gilgamesh at Uruk. Dumuzi the Fisherman is also said to have come from Kuara, which has been identified with modern day Tell al-Lahm, a small town on the northern coast of the Lower Sea, near Eridu, the home of Adapa. Despite it’s size, it was important because it was the central sea port for the Persian Gulf, and relied heavily on sea trade, especially with Dilmun. While Uruk hosted between 50,000 and 80,000 people, spread out amongst 1,000 acres, Kuara was made up of around 5,000, with an urban area of less than 50 acres. If Enkidu came from Kuara, it may have been a culture shock. The deity of Kuara was Asarluhi, a son of Enki, who may have been another name for Dumuzi. A Sumerian hymn to Asarluhi also refers to him as Marduk, who would later become the titular deity of Babylon. Dumuzi’s name may have originally been changed into Enkidu to distinguish him from the god he was named after, or Enkidu may have been Dumuzi’s son who continued the fight with Kish that his father started. If Enkidu can be identified with Dumuzi the Fisherman or a relative thereof, it’s possible he lost a military conflict with Gilgamesh and became his “slave,” as he is referred to in the earliest Sumerian episodes, but then allied with Gilgamesh and went on a war campaign with him to Elam.

Gilgamesh has sometimes been referred to as the Babylonian Hercules within academia, and although the myth of Heracles is rooted in the Mycenaean royal family of ancient Greece, there are some noticeable themes that parallel the two strong-man figures. Both Gilgamesh and Hercules came into on-off conflicts with a the central goddess of their respective pantheons. Hercules was often accompanied by his nephew Iolus, and the stories of Gilgamesh set the earliest example of the sidekick theme. They are both known to have fought lions. Gilgamesh fights the Bull of Heaven and the 7th labor of Heracles was to capture the white Cretan Bull. The theme of twin mountains are found in both stories as well. Gilgmaesh travels to Mount Mashu, which means “twin mountains,” in order to reach the island of Dilmun, and Hercules is said to have opened the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic by splitting the mountain with his club, forming the Straight of Gilbraltor between the “Pillars of Hercules.”

The 11th labor of Heracles was to find the legendary Garden of the Hesperides, which like Dilmun, was located on an island paradise filled with trees. Heracles was to take three golden apples of eternal life from the garden, which he finds in some versions after rescuing Prometheus from his eternal torture by Zeus. In some versions, the apples are guarded by a giant serpent or dragon named Ladon, and similar to the story of Gilgamesh and the haluppu tree in Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, Heracles kills the serpent. The serpent Ladon is named after the seven-headed sea serpent that Ba’al Hadad slays in Ugartic myth. Known as Lotan, it is widely identified with Leviathan, the multi-headed serpent that Yahweh is said to have slain or will slay in Isaiah, Psalms, and Revelation. In Norse myth, the evil serpent Nidhogg, along with other serpents, constantly eat the roots of the World Tree from within the underworld, as it’s resources are consumed by birds and stags living in it’s branches, and replenished by the muddy water of the Norns. The Hungarian world tree was also known for it’s golden apples, the snakes in it’s roots in the underworld, and eagles nested on it’s branches, all forming parallels with the Sumerian haluppu tree. World trees also feature in Chinese, Indian, Greek, Siberian, and Mesoamerican cultures.

In both the Sumerian episode, Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, and the Epic of Gilgamesh, we find the theme of Enkidu, “the son of a fish,” acting as a surrogate who dies in Gilgamesh’s place. This theme resurfaces once again in the early 100’s A.D. in the story of the mysterious death of Antinous, the lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, as mentioned in the last chapter. Antinous is said to have died in Hadrian’s place, and it has been hypothesized that the young man may have committed suicide in order to improve Hadrian’s failing health. Hadrian was himself a worshipper of Melqart, whom the Greeks called the “Tyrian Heracles.” Jesus, likewise, is expressed as having died as a surrogate for the sins of many in both the Pauline epistles and the gospels. Tyre and Sidon, which today are in modern Lebanon, were taken by Jews to be Gentile cities of assumed sinfulness, but the Synoptic gospels reverse this assumption, having Jesus say in Matthew, “it shall be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon in the day of judgment, than for you.” (11:22). He does this to criticize the cities of Korazin, Bethsaida, and Capernaum, saying that if Tyre and Sidon had seen the miracles those cities had, they would have repented long ago.

In trying to learn the origin of Heracles, the “father of history,” Herodotus sailed to Tyre, in Phoenicia, and visited the great Temple of Melqart, which has two great pillars that glow in the night, one of gold and the other “smaragdos” (a green stone, traditionally translated as emerald). The priests at the temple tell him that their temple was built at the same time as the city, 2,300 years ago, which would place it’s construction some time around 2,750 B.C., around the same time Gilgamesh was said to have constructed temples and monuments “for future generations” in the Land of the Living. The city has another temple where the same god is worshipped as the “Thasian Heracles,” which prompts Herodotus to go to the island of Thasos, in the Aegean Sea. There he finds a temple built when the island was colonized by Phoenicians who “sailed in search of Europa.” This temple, he says, was built five generations before the time of the Heracles of Greek myth. All together, this convinces him that there is an ancient god Heracles and the wisest Hellenes are the ones who maintain two temples to Heracles: one to the hero and one to the god. The Greek historian and philosopher Strabo, writing in the early first century, says that in his own time the two bronze pillars in the westernmost temple of Tyre were known as the “True Pillars of Heracles,” but he himself doubts that because the inscriptions on the pillars tell only of the expenses taken by the Phoenicians in constructing them and nothing of Heracles.

Josephus cites a historian named Menander of Ephesus in saying that the temples to Melqart were first consecrated by King Hiram I of Tyre in the mid-900’s B.C. This fits more with the earliest archaeological evidence, which shows that most Phoenician cities of this time replaced the traditional pantheon with a single god and goddess for each city. In Tyre, this was Melqart and Astarte, and in nearby Byblos it was Ba’al Shamem and Ba’alat Gebal. The name Melqart means “king of the city.” King Hiram himself is known in the Old Testament as the king who helped build Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. In 1 Kings, Hiram is said to have cast two bronze pillars, and did some other bronze work for the temple (7:13). In 2 Chronicles, Hiram praises Yahweh and sends a metalworker named Huram-abi to work on the temple, and also sends Solomon wheat, barley, olive oil, wine, even ferries cedar wood down the sea of Joppa for the temple of Jerusalem (2:13). Hiram is said to have brought about sweeping changes during his time, including: building a great royal palace, having engineers use cisterns to catch rain water, and doubling Tyre’s size by joining the island to another nearby island with a landfill. The Freemasons honor “Hiram Abiff” in Masonic ritual, although it is not agreed upon whether he is to be identified with King Hiram or the metalworker Huram-abi.

The “Tyrian Heracles” was possibly the same god that the infamous King Ahab attempted to introduce into Israel. In 1 Kings, Elijah has a contest with 450 of Ba’al’s prophets on Mt. Carmel in northern Israel in which the god who accepted a bull sacrifice by igniting it on fire would be acknowledged as the true god. During the contest, Elijah mocks the priests of Ba‘al, saying, “Cry out loud: for he is a god; either he is lost in thought, or he has wandered away, or he is on a journey, or perhaps he is sleeping and must be awakened.” (18:27). The phrase “on a journey” may be a reference to one of the famed journeys of Heracles or Gilgamesh, while the phrase “wandered away” was probably intended as an insult to suggest that the god had gone off to defecate. The Ba’al cult was ultimately extinguished from Israel by King Jehu, who according to 2 Kings worshipped Yahweh, but did so in the form of the golden bull (11:29).

Archaeological evidence shows that Melqart’s cult spread with Phoenician culture from Tyre, overshadowing the worship of Eshmun in Sidon, moved west into Africa, where Carthage was known to send a 10% yearly tribute to Tyre until the time of Alexander the Great, and went as far west as Spain and Portugal. In 2004, a highway crew discovered a Punic temple in Avenida España, near Ibiza, which held texts mentioning Melqart along with the gods Ba’al, Astarte, and Eshmun. Alexander the Great is said to have visited the Melqart temple that King Hiram had built during his war campaign and worshipped Melqart there before setting fire to the city, which involved building a siege bridge across the coast to the island. Coins minted from the 300’s B.C. show a picture of Melqart’s head that is indistinguishable from Heracles. At least three other temples to Melqart have been found in Spain and Portugal, one of them in Gibraltar, whose influence probably helped bring the naming of the Pillars of Hercules there. The name Hercules itself does not derive from the Greek form Heracles, but instead comes from the Etrsucan form of the name, Heracle, which by 500 B.C. was reduced to Hercle.

|