The Thirteenth Apostle "Although he [Constantine] himself followed another religion, he maintained its own for the empire, for everyone has his own customs, everyone his own rites. The divine mind has distributed different guardians and different cults to different cities. As souls are separately given to infants as they are born, so to peoples the genius of their destiny." -Medieval sourcebook: The Memorial of Symmachus, Prefect of the City

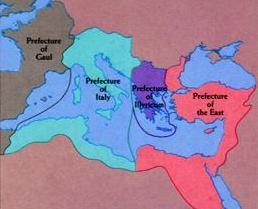

Introduction  Diocletian was at first ambivalent towards the Christian faith, as well as other newfangled "cults" like Manism, but his second-in-command, a Dacian named Caesar Galerius is said to have convinced him that if these foreign traditions were allowed to continue, it would lead to cultural degeneration. This was not Roman cultural degradation that Galerius, “the Drover,” was worried about, though. He was from Dacia, an area in present-day Romania that includes Transylvania, which had fought two short wars with Rome in 101 and 105 A.D. Like most Dacians, he hated Rome; it was the Empire he was interested in. Galerius had already himself decreed that any Christian in his own province who refused to sacrifice would be burned alive. Diocletian was also being told by his soothsayers that Christians who were crossing themselves were offending the gods and making it impossible to auger a reading out of the livers of sacrificed animals. This problem caused Diocletian to hold a conference in Antioch on the problem. It’s said that after consulting an oracle of Apollo, Diocletian began the last and the most destructive of the ten Christian persecutions, which lasted from 303 until 311. According to legend, a Christian soldier named George was ordered to take part in the persecution in the first year of the persecution but instead confessed his faith. He was then tortured with many different devices, including a wheel of swords. He is said to have been killed three times, chopped into pieces, burned, and buried, but each time God brings him back to life. Finally he was decapitated before the defensive wall of the eastern empire’s capital of Nicomedia, and milk pours forth from his neck in the place of blood. George’s suffering is even said to have been so inspiring that an otherwise unknown “Empress Alexandra” and a pagan priest named Athanasius decide to join him in martyrdom. His body was then returned to Lydda, in modern Israel, where his burial ground became a pilgrim spot for Christians. A church was built in his name during Constantine’s reign, and a cult sprung up around his persona. In 495, Pope Gelasius attests to an apocryphal Acts of St. George, and refers to him as one of the saints “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are only known to God.” It would not be until the Crusades that his most popular role as a dragon slayer would be added to his legend. As Europe began looking for ways to combine heroic war stories with the otherwise anti-war themes of Christian literature, stories like that of King Arthur became very popular during the 1100’s, and no doubt played a central part in legitimizing the concept of the Christian warrior. Legends of George riding in and fighting alongside the Crusaders abounded during this time. The church dedicated to George in Lydda was destroyed in 1010 and again by Saladin around 1190. The earliest known legends of St. George and the Dragon comes from around 1260, in Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum historale and then in Jacobus de Voragine’s famous Golden Legend. It’s been theorized the dragon represents Diocletian, who was sometimes called a “drakon,” or that of paganism in general, or that the story is related to other dragon-slaying myths. The legend said that St. George traveled to a town in Libya named Silene, which may supposed to mean Cyrene. Every day the town prepared a lottery to find out which virgin would be sacrificed to the dragon. When the king’s daughter was chosen, he offered all his money and half his kingdom for his daughter to be spared, but the town refused. She was taken out on to a bridge on the lake where the dragon lived, but St. George then rides out. George then made the sign of the cross, which defeats it, or in the later version, weakens it so that he could wound it. He then tells the princess to leash it with her girdle, and the two lead it back to the town where George slays the dragon in front of everyone. Instead of accepting a reward, George asks that everyone be baptized. The town does this and everyone is converted to Christianity. A church to the Virgin mary was built on the spot where the dragon died, and it’s altar was said to have brought forth a spring that cured all diseases. In 305 A.D., twenty years after splitting the empire in two, Diocletian became the only Roman Emperor to ever leave the throne voluntarily. It took some pressure from Diocletian to make Maximian abdicate, but eventually they both stepped down, handing the thrones to Galerius and Constantius Chlorus. Galerius chose Maximinus Daia (a.k.a. Maximin, Maximinus II Daia) as Caesar and Constantius Chlorus chose Severus II. However, the general populace was more accustomed to sons inheriting the thrones of their fathers and the sons of Maximian and Constantius Chlorus couldn't agree more. Constantius Chlorus' first-born son was Constantine, who had been born to his first wife, Flavia Iulia Helena, a 16-year-old daughter of an innkeeper, in the year 272. Constantius Chlorus, who was of Greek descent, left his mother when Constantine was 20 in order to marry Flavia Maximiana Theodora, the daughter of Maximian. Constantine served Diocletian in Nicomedia as a hostage after his father was made a Caesar; this was a common practice to ensure loyalty among the generals. Constantius "the Pale" petitioned several times for his son Constantine be allowed to join him on an expedition in England, but Galerius prudently refused. But eventually, Galerius capitulated and allowed Constantine to go. It was said that Constantine got Galerius to sign the release when he was drunk. The next day, after Galeris had sobered up, he realized how much of a threat Constantine could pose and so revoked the travel orders. But by that time, Constantine and his men had already taken fresh mounts at the first way station and had hobbled the other horses so that Galerius' men couldn't follow them. In 306, Constantius Chlorus and his son went on an expedition against the Picts and the Scots in England. During the campaign, Constantius fell sick. It's said that on his deathbed, he asked his soldiers to give his son Constantine the throne despite the fact that he had already given it to Severus II. When Constantius died, he was raised to the status of divinity, as were all Roman emperors after Julius Caesar. Constantine was declared Augustus by his troops and the new emperor sent a portrait of himself dressed in purple robes back to Galerius, sending the elder tetrarch into a rage. Galerius worked out to compromise with Constantine to make him the Caesar under the new Augustus Severus II in order to avoid a civil war. More trouble arose when Galerius decided that, despite an ancient tradition, the Roman capital should pay taxes just like every other province. Galerius had always hated Rome due to a blood feud tied into his Dacian ancestry. He treated his Roman citizens with equivalent disdain and had even wanted to rename the newly modified empire the Dacian Empire. The city of Rome rebelled and chose Maximian's son, Maxentius, as their new emperor, who then restored freedom of religion to the capital. Maxentius invited his father to help him rule, and still eager for power after 20 years of being an Augustus, Maximian accepted. Galerius sent Severus II on a forced march to put down the rebellion in 307, but the soldiers were veterans from Maximian's army and were easily bribed by Maxentius. Severus II surrendered and was was put to death, leaving Galerius to come and settle it himself. But Galerius' campaign fared even worse and mass desertions caused the Augustus to turn around even before he got to the capital. To placate the remaining loyalists, he allowed the army every excess imaginable and a wake of rape and terror followed him back to his province. With that victory, Constantine decided to throw his chips in with Maxentius, although he still wanted to keep good relations with Galerius if possible. Like his father, Constantine left his wife in order to marry a daughter of Maximian, Fausta, and was summarily raised to the rank of Augustus. He had been engaged to Fausta for over 10 years, but had stayed married to his low-born wife during the engagement. No official divorce decree was made so he most likely "put her away" the same way that his own father did to Constantine's mother Helena. Soon enough, Maximian grew jealous of his son and tried to depose him, but found, to his surprise, that the soldiers were on his sons' side. The conflict came to blows in front of a public audience. Maximian beat his son down and then tore off Maxentius' purple robes before his son's personal guard could whisk the young man away. With Maxentius' army planning revenge, Maximian fled the capital. Now free of his father, Maxentius proclaimed himself Augustus, the fourth man in the empire to give himself that title, along with Galerius, Maximian and Constantine. While there were four Augusti, there was actually only one Caesar, Galerius' nephew, Maximinus Daia. Constantine decided to make his alliance with the elder Maximian against Maxentius. A peace conference was called and Diocletian came out of retirement to preside over it. It was decided that Maximian would again abdicate, Constantine would be demoted back to Caesar, and Licinius, a long time friend of Galerius but a new player in the Tetrarchy, skipped past Caesar to be made Augustus of the west, much to the dismay of Constantine and Maximian. Maxentius, who was being supported by the Praetorian Guard in Rome, was designated as a rebel and was left out entirely. What was worse for Maxentius was that when he ordered his vicarius in Africa, Domitius Alexander, to send him his son as a hostage, the deputy refused and instead proclaimed himself emperor. Domitius Alexander allied himself with Constantine and Maxentius' critical food supplies from Africa became threatened. Some time around 310, Maxentius sent a small army to Africa, had the rebel executed, and seized all his assets. Once again it seemed that Rome's ruling class had been able to set the Empire back on the path towards stability, but much to Diocletian's dismay, his one-time co-emperor Maximian would not take being put back into retirement so peacefully. Maximian soon began looking towards Constantine's throne in Gaul (France) as his way back into power. While Constantine was away fighting in Germany, Maximian spread rumors of Constantine's early demise and declared himself emperor for a third time. Word of this made it to Constantine, who returned prematurely, forcing Maximian to flee sotuh to Massilia (Marseille). Constantine chased after him and put the city under siege. It's said Constantine gave a charismatic speech to the enemy soldiers, explaining the foolishness and injustice of their actions. When Maximian replied with nothing but abusive language, the rebel soldiers surrendered to Constantine. Maximian died soon afterwards but there is legend that says Constantine let him live until the emperor decided to betray Constantine again. It's said that Maximian tried to convince his daughter Fausta to leave Constantine's bed, distract his bodyguards, and leave the rest to him. In return, she would be married to someone more deserving of her. More loyal to her husband than to her father, Fausta warned Constantine of his plot and a eunuch was substituted in his place. Maximian soon came and saw that the chamber had only a few guards, and so accosted them, telling them that he had had a dream that he needed to inform his son-in-law of. Once he got close enough to the bed, he murdered the eunuch and ran out proclaiming his success, only to find Constantine and a large number of soldiers waiting for him. Maximian was immediately captured and, being allowed to choose his form of death, he chose to strangle himself. Constantine had all statues and inscriptions of Maximian burned, including the ones of him with Diocletian. When news of all this reached Diocletian, he went insane with grief, calling out for death to release him from his indignity.  Diocletian and Maximian, best buddies forever The Batle of Milvian Bridge It was a common belief that Rome's war on Christianity was stopped by the divinely influenced Constantine, but the first Edict of Toleration was not brought forth by him, but by the same person who had convinced Diocletian to enact the last great persecution in the first place, Galerius. A sexual disease had spread throughout his body, infesting his body with worms and causing him great torment. When prayers to the traditional gods did nothing to ease the pain, he enacted the Edict of Toleration, hoping for divine relief from the god of his enemies. This was probably done at the suggestion of his Christian wife, Valeria. The edict began with curses and rebukes towards the arrogance and stupidity of those who refused to uphold the traditions of their anscestors and ends with capitulance on the condition that for this clemency the fool-hearted pray to their god for the health and prosperity of the Augustus. The edict was published throughout the territories of Galerius, Licinius and Constantine, although religious tolerance was already being practiced under Constantine. Galerius died just a few days later and Maximinus Daia took his place as Augustus. Although he did not officially withdraw the edict, in practice Daia conducted an offensive against Christians under different pretexts, even forcing some to conduct masses in the cemetaries. Meanwhile, things went poorly in the one-time capital of Rome, the seat of the rebellion. A revolt against the rebellion in one of the territories had left Maxentius poorly supplied. After putting down the revolt and increasing the taxes, he began allowing his soldiers to steal from the citizens. Constantine cemented his alliance with the new Augustus Licinius by giving his daughter Constantia to him in marriage. He then took 40,000 of his best men and began his march to Rome against his brother-in-law. Although some legends say a sign in the sky was seen in the eve of battle, the Roman Church historian Eusebius accounts that the sign was seen long before he reached the capital. Eusubius was told this by Constantine himself and gave an oath to it's truth. Constantine had been praying for assistance to the god of his father, Sol Invictus, the Unconquerable Sun, when not just he but his whole army saw a dazzling labarum, or 'chi-ro'. The first two letters Ch-R were taken to stand for 'christos', which is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word 'messiah', literally the 'anointed one'. The labarum stood in front of the sun along with the motto 'By this sign, you will conquer'. This had not been the first vision Constantine saw. He had previously claimed to have seen Apollo during a visit to one of the sun god's shrine, as well as the Roman goddess Victory. That night he dreamed of the Anointed One of God with the sign he had seen in the sky. Christ then told him to make standards of that symbol for protection, which he did. The labarum was a popular symbol that had been printed on many Roman coins beforehand, and was a symbol used in Mithraism. Mithraism is a Greek-based religion derived from the ancient Zoroastrian deity, Mithra, originally one of the lesser deities who served under Ahura Mazda, God of Light. From the little that is known about Mithraism, it is commonly accepted as being equivalent to Constantine's sun worship. Starting in the 200’s A.D., the birthday of Sol Invictus/Mithras was celebrated throughout the Roman Empire on December 25th, supplanting the older Roman holiday, Saturnalia. The Romans celebrated Saturnalia on December the 17th, which slowly moved to December the 23rd until it was supplanted by the Mithraic festival of Sol Invictus, the god of Constantine’s original Persian religion. This festival was on December 25th, was introduced in the early 200’s A.D. but was made an empire-wide festival by Emperor Aurelian in the 270’s. In 245, Origen denounced the idea of celebrating Jesus’ birthday “as if he were a king pharaoh, but in 354, Christmas first appeared on the Calendar of Filocalus.  Constantine invaded Italy, taking the cities with great military genius, and often fighting in the front ranks. In one instance, he feigned a retreat to break the compact ranks of the enemy and then brought in reserves with heavy maces into the heart of the battle. When Maxentius heard of Constantine's victories, he went mad with fright and is said to have turned to disemboweling pregant women and young babies to use their entrails for prophecy. He showered his soldiers with money. Although he had kept himself within the walls of Rome because of a prophecy that he would otherwise die, he took comfort in the Sibylline books which said the enemy of Rome would die the very day Constantine would march on the city. Thinking it referred to Constantine, Maxentius led his army outside the huge walls of the city even though he had enough supplies to outlast a siege. Maxentius' generals chose a poor spot of defense and when the battle began, he was soon routed by Constantine's superior battle tactics. Maxentius' army tried to escape over the Milvian Bridge but it collapsed under their retreat and many more drowned while trying to cross it in boats. Maxentius' drowned body was found the next day and his head was stuck on a pike and carried around Rome in triumph. Constantine reinstated the Senate and dismissed the surviving Praetorian Guard, who until then had made and unmade the rulers of the world. A great arch was dedicated to him to commemerate his victory and he was given the title 'First of the Augusti' by the Senate in 312 A.D. Soon afterwards, he celebrated Constantia's marriage with Licinius. Diocletian may have formally been the worst persecutor of Christianity to date, even surpassing that of Nero, but the founder of the Tetrarchy was still invited to the wedding. In Rome, Constantine had found statues and increminating letters proving that Galerius' nephew Maximinus Daia had been plotting with Maxentius against him. Constantine had the statues destroyed. Maximinus Daia, who recently returned from a campaign against the Armenians to the east, tried to strengthen his position by attempting to marry his dead uncle's wife, Valeria, who was living in his province. Valeria responded that she was still wearing her widow's weeds and that Maximinus Daia's present wife had done nothing to deserve repudiation, writing, "Even if honor could permit a woman of her character and dignity to entertain a thought of second nuptials, decency at least must forbid her to listen to his addresses at a time when the ashes of her husband, and his benefactor were still warm, and while the sorrows of her mind were still expressed by her mourning garments. She ventured to declare, that she could place very little confidence in the professions of a man whose cruel inconstancy was capable of repudiating a faithful and affectionate wife." For this Maximinus Daia began to hound her as well as torture and kill her friends, relatives and staff. He began moving her throughout the province 'for her safety'. Diocletian sent representatives to try and stop him from doing this to his daughter, but Maximinus Daia only replied in abuse. Instead of publishing the revealing documents of Maximinus Daia's secret alliance, Constantine sent notice to Daia of Maxentius' defeat and ordered him to stop his persecutions against Christianity. Maximinus Daia replied that although he had been trying to persuade his subjects to return to the traditional worship with kindness, he was still a firm supporter of religious toleration. But this was only a ruse. Licinius had to break off his honeymoon early when he learned Maximinus Daia was invading his territory, in winter no less. Dealing with barbarians in the west, Constantine could not come to Licinius' aid. In April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and took the city of Byzantium (Istanbul) after an 11 day siege. He moved on to Heraclea, which he captured after another short siege. Licinius then arrived with a small army. It was said that Maximinus Daia had sworn to Jupiter that if he won the upcomming battle, we would destroy the new religion once and for all. A short time before the battle, Licinius was said to have had a dream that corresponded closely to Constantine's, where an angel taught him a prayer to recite to his army. It was rather generalized monotheistic prayer that would appeal to soldiers of many faiths, and it is said they recited it three times before the fight. No agreement was reached in the parlay and the battle went against Maximinus Daia shortly after it started. His personal guard defected, and he tossed his purple robes away and disguised himself as a slave, retreating to the city of Nicomdeia, back in his territory. When Licinius had him surrounded, he made two provisions, one issuing total liberty to the new religion and another to kill all the pagan priests who had goaded him to war. He then poisoned himself. After Licinius took the city, he began brutally executing everyone remotely associated with Maximinus Daia. Convinced that Licinius was worse than Daia, Valeria and her mother Prisca escaped the city and wandered the provinces for about 15 months disguised as plebeians. They were eventually discovered at Thessalonica, and as the sentence of death was already pronounced, the two women were immediately beheaded, and their bodies thrown into the sea. Dioceltian also died around this time. His death followed a long and painful illness according to Eusebius but other sources say it was due to self-starvation. No one knows when it happened. At the age of 59, he had retired and was growing cabbages at Salona, on the Adriatic Sea, since 305, after he had suffered a near-death sickness. It is said that when he was asked to return and resume his honors as emperor, his reply was "Would you could see the vegetables planted by hands at Salona, you would then never think of urging such an attempt." The Edict of Milan With Maximinus Daia gone, Constantine and Licinius created their own edict of toleration two years' after the one reluctantly written by the ailing Galerius. This one, called the Edict of Milan, had the empire take a far more neutral position towards religion, putting great emphasis in quelling fears that an emperor following the new religion would persecute the old. In 391 A.D., those fears were realized with the illegalization of paganism during the reign of Emperor Theodoseus. Principal among the adherents of pagan abolishment were Constantine's sons. After striking this new alliance with Licinius, Constatine began to change. Before he had celebrated his victories with bloodthirsty shows, but now he closed down the gladiatorial matches being held in the Colloseium. (The stadium itself had been been built partially by Jewish slaves captured during the sacking of Jerusalem and destruction of the Second Temple). For the first time, laws were passed against rape, abducting women as wives, concubinage, child prostitution, and adultery. The fact that Constantine's mother was a 16-year-old tavern girl given to his father as a consort may very well have been an inspiration behind this. Constantine also passed many new laws favoring Christianity. He ended the practice of branding slaves on the face, although branding them on other parts of the body was still permissable. Slaves could be beaten to death by their masters and unlike the laws of Diocletian, children were allowed to be bought and sold. Slaves who sought refuge among barbarians were to have a foot amputated. Following Diocletian's example in trying to keep jobs passing from father to son, Constantine passed laws making the occupations of butcher and baker hereditary and reformed the coloni system, changing tenant farmers into serfs, thus laying the foundation for medieval society. Sorcery was forbidden as it always had been. He began giving sermons preaching harmony and the uselessnes of pagan temples. Although he toyed with the idea of closing the old Roman temples down, he decided to shut down only certain temples, both pagan and Christian, that were known to have immoral practices. Oracles were forbidden in private houses but were allowed in public. Constantine himself had an oracle consulted when lightning struck the imperial palace. Although Constantine kept the emperor's title of "Pontifex Maximus" (High Priest of the Roman pantheon), and used coins bearing the inscription of Sol Invictus, he began to present himself to Christians as "Bishop of those outside" (meaning outside the religion) and even gave himself the title of "The Thirteenth Apostle". He is still considered by some to be a 'pari-apostle' and is listed as a saint of the Greek Orthodox Church.  Soli Invicto Comiti, "To the Sun, My Invincible Companion" When barbarians invaded the east, Constantine came to Licinius' aid, beating them back. But Licinius used Constantine's intrusion as an excuse to make war on him, and the two fought in the same battlefield Licinius had defeated Maximinus Daia in. This time Licinius lost the fight and tried to escape by sea, only to be hit by bad weather and then cut off by Constantine's son and newly-appointed Caesar, Crispus. He fled Byzantium and regrouped for another fight in Chrysopolis, but was routed once again. Like Maximinus Daia, he holed himself up in Nicomedia until Constantine had him surrounded. Licinius surrendered, and following an impassioned plea from Constantia, was put under house arrest in Thesalonica. However, Constantine had him executed in 325, some say because he was planning another rebellion. With Licinius gone, all of his lands came under the control of Constantine. Rome was once again a monarchy. The Council of Nicea While Constantine had to fight off Licinius, he also had to deal with the Donatists, African hard-liners who brought about a schism within Christianity over whether sacraments performed by those who lapsed during the persecutuions were still valid. They believed anyone who handed over holy scripture or betrayed other Christians had to be rebaptized into the church. But the matters were more than theological and spilled fanatically into daily life, with the Donatists calling themselves the 'Church of the Martyrs' and the Catholic church, the 'Church of the Traditores'. The Donatists were founded by a Berber Christian named Donatus and had become the Christian majority in North Africa. The conflict started when the Bishop Mensurius from Carthage, Africa, was accused of handing over sacred texts to Roman authorities. The bishop admitted to handing over scripture, but claimed that he had substituted heretical texts for true scripture and was never asked for any more. In his city, Mensurius actually dealt with the problem of Christians enthusiastically turning themselves in to Roman authorities, attempting to instill on them not to seek martyrdom for martyrdom's sake. Mensurius had written in to Rome that he had denied the title of martyr to many whom were captured or killed by Roman authorities because they were criminals or debtors who he believed turned themselves in to Rome in order to receive Christian charity in the relative security of prison. When Mensurius died, he was quickly replaced by a man named Caecilian, who the Donatists accused of barring the jail by using a leather whip against any Christian charity-givers. The food meant for Christian prisoners was fed to dogs while captured Christians died of starvation, although Caecillian denied it. Constantine attended many meetings and trials to mediate the problem, but ruled the charges against the traditores groundless. Constantine even attempted to detain both Donatus and Caecilian in order that the Carthaginians vote for a new bishop in both heiarchies in order to keep the peace, but this compromise wasn't accepted either, so Constantine finally decided to banish the leaders of the Donatists. He ordered the confiscation of Donatist churches and sent his soldiers in to take over the bascilla. Many women were raped and men killed, but the Donatist cause would continue until another purge. This last purge came from Emperor Horius, who along with the esteemed Roman Catholic church father St. Augustine, made one more attempt at reconcilliation before setting a law against the faction in 412, confiscating their churches and forbidding them to meet one another. Then there was the Arian heresy, which had a lot of support in Egypt. Arianism was and is the belief that the Son of God is inferior to that of the Father and was created at some point in time rather than being coeternal with Him. (Modern scientific evidence regarding the relativity of time to space only renders such differentials all the more subtle.) The heterodox sect was named after the Egyptian Christian priest from Alexandria named Arius. Arius was accussed by the bishop Alexander of having a disappropriate number of women in his congregation, and accused his female congreagation of having loose morals. One source said Arius had 700 dedicated virgins, who were all set aflame by him. Arius' teachings followed that of the revered martyr Lucian of Antioch, and was also in the tradition of the church father Origen of Alexandria. By this time, Constantine was growing quite weary of the factionism within Christianity. He wrote of the matter as a "small and useless contest of words", that such questions were "vulgar things and expected of foolish children, but not suited to the good sense of priests and prudent men". He decided that the only way to quell the theological arguing was to enact a great council to decide the dogma of Christianity once and for all, inviting some 300 bishops and 700 attendants to the First Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. Of these 300 bishops, none were of Jewish descent and only four were from the western side of the empire. Constantine was very respectful to the bishops, especially those who had undergone torture for their beliefs. He even kissed the empty eye socket of bishop Paphnutius of Egypt. But he also lorded over the council in a raised throne of gold, with his advisor in theology, Horius, standing next to him. The church historian Eusebius wrote:

"Detachments of the bodyguard and troops surrounded the entrance of the palace with drawn swords, and through the midst of them the men of God proceeded without fear into the innermost of the Imperial apartments, in which some were the Emperor's companions at table, while others reclined on couches arranged on either side. One might have thought that a picture of Christ's kingdom was thus shadowed forth, and a dream rather than reality."

The council was suppossed to touch on a great number of subjects, but the majority of the time was centered on the divine status of Jesus. Arius began to read his speech, 'Thalia', on how Jesus was not coeternal but of a different essence than the father:

"God himself then, in His own nature, is ineffable by all men, equal or like Himself He alone has none, or one in glory. And ingenerate we call Him, because of Him who is generate by nature. We praise Him as Unoriginate because of Him who has an origin. And adore Him as everlasting, because of Him who in time has come to be. The Unoriginate made the Son an origin of things generated; And advanced Him as a Son to Himself by adoption. He has nothing proper to God in proper substance; For He is not equal, no, nor one in substance with Him. Wise is God, for He is the teacher of Wisdom. There is full proof that God is invisible to all beings, Both to things which are through the Son, and to the Son is He invisible."

Many in the congregation closed their ears to the blasphemy. A letter from Bishop Alexander lays out his own very intricate definition of the Father-Son relationship that he portrayed to the council:

"Thus there are Three Subsistences. And God, being the cause of all things, is Unoriginate and altogether Sole; but the Son being generated apart from time by the Father, and being created and founded before ages, was not before His generation, but being generated apart from time before all things, alone was made to subsist by the Father. For He is not eternal or co-eternal or co-ingenerate with the Father, nor has He His being together with the Father, as some speak of relations, introducing two ingenerate origins, but God is before all things as being a One and an Origin of all. Wherefore also He is before the Son; as we have learned also from thy preaching in the midst of the Church. So far then as from God He has His being, and glories, and life, and all things are delivered unto Him, in such sense is God His origin. For He is above Him, as being His God and before Him. But if the terms from Him and from the womb, and I come forth from the Father, and I am come, be understood by some to mean as if a part of Him, or as an issue, then the Father is according to them compounded and divisible and alterable and material, and, as far as their belief goes, has the circumstances of a body, who is the Incorporeal God."

In simpler language, it could be said that the question was over which of these two Gospel verses best describes the relation Jesus has with God:

Wanting to see the tomb of Jesus, legend says Nicholas once took a ship to Jerusalem and dreamed of Satan. He warned the crew of a storm but assured them they wouldn't die. When the storm came, the wind blew a man off the mast and he hit the deck, dead. Nicholas stopped the storm and then resurrected the sailor. He then cured many sicknesses in Jerusalem but wasn't allowed to rest there because he was immediately called by God to go to a city on the other side of the Mediterranean. The captain of the ship agreed to take him there, but once out to sea the sailors decided they wanted to go home and turned the ship back, but another storm brought them to the original destination, where the bishop had recently died. An angel came to an appointed priest and told him to make the next bishop Nicholas, and just as the angel predicted, Nicholas walked into the church the next day and so was made a bishop. If Nicholas the Confessor did attend the council, it can be imagined that he argued passionately against Arius. As an adherent to homoousion, he would have tried to convince Arius that if the Son was just a creation, then it would be just as idolatrous to worship Jesus as it would be to worship the angels. Arius, however, denied that it was a sin to worship Jesus, and argued that the title "Son of God" insinuated inferiority to the Father, saying, "What argument then allows, that He who is from the Father should know His own parent by comprehension? For it is plain that for that which hath a beginning to conceive how the Unbegun is, or to grasp the idea, is not possible." And then Santa Claus clocks him. That is what the legend says, anyway. The violent gesture is said to have gotten him banished from the council and relieved of his bishop status. Another legend says that he was sent to prison, and while languishing there, was visited by Jesus and the Virgin Mary because of his love for them. Jesus gave him a gospel and the Virgin Mary gave him a bishop's garment. Many priests and bishops had dreams that night in which Nicholas was venerated by God for his zeal against heresy, and so they begged Constantine to release him, which Constantine did after seeing Nicholas produce the gospel and bishop's garment from behind bars. Another legend involving St. Nicholas says that Constantine once sent soldiers to the bishop's city Myra to put down a rebellion, but the solders began to sack the city instead, so Nicholas reported the activity to the three generals that Constantine had sent, telling them they had been sent to stop a rebellion, not to start one. Unaware of what the soldiers were doing, the generals, named Nepontianos, Orsos, and Erpillion, restrained their men. The district judge tried to put the three generals to death, but Nicholas stepped in, reprimanded the judge, who then begged forgiveness. After the rebellion was put down, the three generals were arrested in Constantinople after being framed by a magistrate being bribed by Constantine's enemies. Nicholas appeared to Constantine in a dream to warn him that the three soon-to-be-executed generals were innocent. After learning the magistrate had the same dream, Constantine released the three generals, begged their forgiveness, sent them each a golden gospel and incense burner, and then sent them back to Nicholas, who baptised them. Thus he became the patron saint of the falsely accused. The destruction of several pagan temples are attributed to St. Nicholas, including one dedicated to Artemis (known to the Romans as Diana). Because Artemis' birthday was December 6, it has been speculated that Nicholas' feast day was deliberately chosen to overshadow the pagan celebration. This would be consistent with the practice of the times as every Christian holiday celebrated has its origin in paganism. Nicholas' popularity skyrocketed during Medieval times; the propensity of paintings of Nicholas was matched only by the Virgin Mary and nearly 400 churches were dedicated to him in England during the late Middle Ages. In time, legends of his gift-giving began to be substituted for the German legends of Odin and Thor. Exchanging gifts during the winter solstice had been a practice in Europe since time immemorial. St. Nicholas was depicted as riding a grey horse as he visited childrens' homes, just as Odin rode his flying gray horse, Sleipnir. Thor, whose home was in the snowy "Northland", likewise rode a chariot through the air pulled by two white goats, Cracker and Gnasher. Thor was also said to be friendly and cheerful, and would come down chimneys into the fire, which was his natural element. Other legends of St. Nicholas told of how he would bring his elf, Black Pete, whose job was to punish bad children. After the Protestant Reformation, Nicholas' following dwindled in the west, except in Holland where his legend continued as Sinterklass. In Germany, Martin Luther tried replacing the bearer of gifts with Christkindl, the "Christ Child", but the name was only transferred over to St. Nicholas so that Kriss Kringle is now an alias for Santa Claus. Whether Nicholas was at the council or not, the deliberations were made and a vote was cast to determine the relationship of the Son to the Father. Bishop Athanasius' side won by five votes (or perhaps one K.O.). Jesus was now officially God. The Arians complained that the edict had already been decided by Horius and Alexander before the council was convened, but only Arius and two other bishops refused to sign the edict. Constantine had made it clear that a decision had to be made and universally accepted. Those who did not sign were exiled. Everyone else was required to repeat the Nicene Creed in order to prove that they held the dogma of the Orthodox Church. A heavily edited version of the Nicene Creed is still recited in every Roman Catholic liturgy today. The original Nicene Creed is as follows: And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father, only-begotten, that is, of the substance of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through whom all things were made, things in heaven and things on the earth; who for us men and for our salvation came down and was made flesh, and became man, suffered, and rose on the third day, ascended into the heavens, and is coming to judge living and dead. And in the Holy Spirit. And those that say 'There was when he was not,' and, 'Before he was begotten he was not,' and that, 'He came into being from what-is-not,' or those that allege, that the son of God is 'Of another substance or essence' or 'created,' or 'changeable' or 'alterable,' these the Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematizes."

Clearly, one part of the Trinity interested the bishops more than the others.

"When the question relative to the sacred festival of Easter arose, it was universally thought that it would be convenient that all should keep the feast on one day; for what could be more beautiful and more desirable, than to see this festival, through which we receive the hope of immortality, celebrated by all with one accord, and in the same manner? It was declared to be particularly unworthy for this, the holiest of all festivals, to follow the custom [calculation] of the Jews, who had soiled their hands with the most fearful of crimes, and whose minds were blinded. In rejecting their custom, we may transmit to our descendants the legitimate mode of celebrating Easter, which we have observed from the time of the Savior's Passion to the present day [according to the day of the week]. We ought not, therefore, to have anything in common with the Jews, for the Savior has shown us another way; our worship follows a more legitimate and more convenient course (the order of the days of the week); and consequently, in unanimously adopting this mode, we desire, dearest brethren, to separate ourselves from the detestable company of the Jews, for it is truly shameful for us to hear them boast that without their direction we could not keep this feast. How can they be in the right, they who, after the death of the Savior, have no longer been led by reason but by wild violence, as their delusion may urge them? They do not possess the truth in this Easter question; for, in their blindness and repugnance to all improvements, they frequently celebrate two passovers in the same year. We could not imitate those who are openly in error. How, then, could we follow these Jews, who are most certainly blinded by error? for to celebrate the passover twice in one year is totally inadmissible. But even if this were not so, it would still be your duty not to tarnish your soul by communications with such wicked people. Besides, consider well, that in such an important matter, and on a subject of such great solemnity, there ought not to be any division. Our Savior has left us only one festal day of our redemption, that is to say, of his holy passion, and he desired [to establish] only one Catholic Church. Think, then, how unseemly it is, that on the same day some should be fasting whilst others are seated at a banquet; and that after Easter, some should be rejoicing at feasts, whilst others are still observing a strict fast. For this reason, a Divine Providence wills that this custom should be rectified and regulated in a uniform way; and everyone, I hope, will agree upon this point. As, on the one hand, it is our duty not to have anything in common with the murderers of our Lord; and as, on the other, the custom now followed by the Churches of the West, of the South, and of the North, and by some of those of the East, is the most acceptable, it has appeared good to all; and I have been guarantee for your consent, that you would accept it with joy, as it is followed at Rome, in Africa, in all Italy, Egypt, Spain, Gaul, Britain, Libya, in all Achaia, and in the dioceses of Asia, of Pontus, and Cilicia. You should consider not only that the number of churches in these provinces make a majority, but also that it is right to demand what our reason approves, and that we should have nothing in common with the Jews. To sum up in few words: By the unanimous judgment of all, it has been decided that the most holy festival of Easter should be everywhere celebrated on one and the same day, and it is not seemly that in so holy a thing there should be any division. As this is the state of the case, accept joyfully the divine favor, and this truly divine command; for all which takes place in assemblies of the bishops ought to be regarded as proceeding from the will of God. Make known to your brethren what has been decreed, keep this most holy day according to the prescribed mode; we can thus celebrate this holy Easter day at the same time, if it is granted me, as I desire, to unite myself with you; we can rejoice together, seeing that the divine power has made use of our instrumentality for destroying the evil designs of the devil, and thus causing faith, peace, and unity to flourish amongst us. May God graciously protect you, my beloved brethren."

In this letter, Constantine bears no timidness in revealing his unquenchable hatred of the Jews. He even stops to remind the reader to be as different as possible as the “murderers of our Lord,” an ironic position to take for someone who just oversaw a council that elected a Jew as being co-existent with God. One might think that Jesus wasn't hung on a Roman cross. Unfortunately, it would become an reoccuring convention that many who inherit an essentially Jewish religion come to revile the cultural roots of their faith.

"Nothing that Constantine the Great did shows his ability more clearly than his seizing upon the site of old Byzantium for the location for his new capital. The place was admirably sited for an impreial residence, being over against Asia which the Persians were threatening, and in easy touch with the Danube, where the Northern Barbarians were always swarming. Note that Constantinople was from the outset a Christian city; as contrasted with Old Rome, where paganism still kept a firm grip, at least on much of the population, for nearly a century." -Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, 450 A.D.

After time, Constantine tried to compromise with the Arians in Egypt and talked Arius into signing a creed that didn't contain the word homoousion in it. Athanasius, however, wielded a vast amount of popular support and was not afraid to back up his theological views with force. Although this aspect has been downplayed by church historians, modern scholars like Duane Arnold, Timothy Barnes, and David Brakke have written books on how Athanasius used threats, bribery, theft, extortion, murder, and the instigation of riots to push his ecclesiastical agenda with the justification that he was trying to save Christians from going to hell for accepting false dogma. Naturally, Athanasius refused to accept Arius, causing Constantine to convene the Council of Tyre in 335, a full decade after Nicea, with Count Flavius Dionysus at the head of 300 bishops, 50 of them from Egypt. Arius charged Athanasius with supporting violence and Athanasius was spit on by some of the council members. Constantine found Athanasius guilty of hindering the transport of grain to New Rome and was exiled. Arius was absolved from all censure and restored to his ecclesiastical position, something the bishop of Egypt was not prepared to do. A week before the deadline, Arius was walking around the city with his friends and stepped into a private restroom where a massive hemorage disembowed him, most likely due to poison. Despite Constantine's reversal, Arius would be forever remembered as a heretic while Athanasius would be brought back from exile into the church by Constantine II, made a saint, and dubbed the "Father of Orthodoxy." |