Religion Before Adam

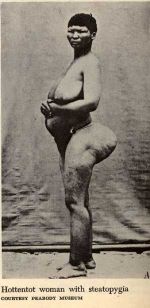

The Age of the Goddess Prehistoric “Venus” Figurines discovered throughout Europe and Asia show a remarkable resemblance to one another Some Venus figurines were carved as far back as 27,000 B.C., but the majority of them have been dated between 23,000 B.C. and 21,000 B.C. The latest figurines found date to about 12,000 B.C. The most famous of the Venuses is the Venus of Willendorf, carved around 25,000 B.C. in Germany and discovered in 1908. Some 350 of these same goddess figurines were found in a stone age site in Israel dating back to the Yarmukian culture, which existed between 5500 to 5000 B.C., near the mountain city of Har Meggido (identified as the site of the final battle between good and evil in the Book of Revelation, giving root to the name of the English word ‘Ar-mageddon’). It has largely been assumed that the exaggerated breasts and hips were meant to emphasize fertility. However, another suggestion first raised by Édouard Piette is that the shape represents a genetic characteristic known as Steatopygia, in which high amounts of fat are stored in the breasts and buttocks, reaching it‘s maximum development in women during pregnancy. This genetic trait is found throughout Africa, where it allows hunter-gatherers to store fat during the dry season when there is little to eat. It’s often accompanied by an elongated labia that can hang three or four inches below the vagina. Some of these women were paraded around Europe as an exhibition during the 1800’s. This trait has been most closely studied in the Khoi-san “bush men” of southern Africa, where it is considered to be a trait of beauty. It has even been suggested that the perceived preference for large posteriors predominate in African Americans is caused by a hereditary trademark of this ancient survival adaptation. However, the connection is tenuous and other explanations abound; for example, it has been pointed out there are striking similarities between the Venus of Willendorf and a pregnant woman when looked at from above.

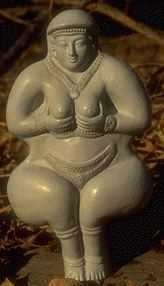

Their belief systems of the Khoi-Khoi are varied: many worship a supreme sky god named Gauna, who presides over daily life and can kill people with arrows from behind the stars, somewhat like Apollo, as well as an evil trickster god who could transform himself into animals and return from the dead. Some perform rituals and small sacrifices to the sky god while others believe it’s best not to attempt communication in fear of summoning the evil god. Ancient spirits, which are different in every social group, are considered to be more relevant to spiritual life. A famous hunter, sorcerer, and warrior from Khoi-khoi mythology named Heitsi, or Heitsi-eibib, was worshipped as god of the hunt and said to have been born from a virgin cow after it ate some magical grass. Various myths tell of how he tricked a monster named Ga-gorib (gorib meaning “spotted”) into falling into the magical beast’s own pit, but in other versions he is said to have been killed by the monster and returned from the dead. Little can be proven regarding the beliefs of those who carved the Venus figurines those thousands of years ago, and despite many shared characteristics, there has been a great reluctance to identify her as the same earth goddess known throughout Paleolithic Europe from 7,000 to 1,700 B.C. But the significance of the lack of variety in these idols through such a large amount of time and space I believe suggests something that is unthinkable to historic sensibilities: prehistoric monotheism. This seems incredible because by the dawn of written word, the world was almost entirely polytheistic. The first archaeological evidence of monotheism being practiced is that of the cult of sun god Aten in Egypt in the 1300s B.C., started by the “heretic” pharaoh, Akhenaten, and it is not generally believed to have gone very far. Adam is usually dated to 4004 B.C., but it is Abraham, who is believed to have lived some time around 1600 B.C., who is usually given credit as being the first monotheist. Today about 53% of the world believes in one God due to a monotheistic revolution that spread throughout the western world starting with Judaism and Zoroastrianism some two millennia ago. Although Judaism now only makes up 0.2% of world religions today (and Zoroastrianism making up far less), the monotheistic revolution spread to both Christianity (33%) and Islam (20%), and now maintains a slight majority in world opinion. If these idols really are heirlooms from a long lost monotheistic age, then perhaps we can think of there having been a polytheistic revolution that took place some time before the first known language. This may have been linked to the establishment of cities, in which city councils began to take on a larger role in centralizing governments, which mirrored the concept of a “council of gods” that governed the world. The predominance of feminine iconography must also prompt us to re-evaluate the way history looks at prehistoric man. How can we reconcile this predominantly feminine form of veneration with the common portrait of ancient life consisting of violent social groups ruled by instinctive alpha males who follow the animalistic urges of their Freudian Id and horde the tribe’s women as concubines? Were women completely dominant over men in some long lost matriarchal age? Or was the figure not so much a glorification of an actual deity but more of an abstract symbol of life? The lack of information begs for speculative bridges to be constructed. One suggestion from scholars that provides a psychological answer to the question is that before the institution of marriage was popularized, polygamy was very comon and people often did not know who their father was. Since the mother was the primary caregiver, she devleoped into the most common role model and authoritarian figure to be imitated in divine conceptualizations until the developement of cities and centralization of society brought forth the nuclear family and transferred authority to the Father in both the divine and corporeal realms. Although nearly if not every known ancient city in ancient history was male-dominated, I beleive that there is good evidence this ultra-culture that centered on the feminine aspect of spirituality did not immediately die out with the advent of civilization. Excavations of the Neolithic settlement in Chatal Hyuk, Turkey, dated to around the 6700’s B.C., have turned up a far greater number of “earth mother” figurines over that of the male god, one of them being a large goddess sitting on a throne flanked by two lions. Hundreds of bear goddess figurines have been discovered around Celtic Gaul and Britain and dated to 5,000 B.C. The figurines portray a mother bear nursing her cubs, which has had a long association with feminine fertility. In fact, the term to “bear children” comes from this association with the bear, in that the Scottish word for child, “bairn,” is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word for bear, “beran.” Sumerian statues dated to around 2,000 B.C. portray the fertility goddess Inanna with features too similar to the Venuses to be coincidental: large breasts covered by small hands and a barbell shape very reminiscent of the prehistoric Venuses. Although the Sumerian statues have faces on them, the same bead-like circles of the Venuses can be found around their head and pubic area. There are also a lot of contradictions within Sumerian sources as to how Inanna fits into the Sumerian pantheon’s family tree, which suggests the deity was embedded into the mythology at different times by different people. Unlike most of the other gods, who are repeatedly referred to as bull gods, Inanna’s totem animal is that of the lion. However, the connection between the Paleolithic Venus figurines and the goddesses of "earth mothers" of Chatal Hyuk and the Sumerian societies have been greatly contested, most especially due to the absense of archaeological evidence in the intervening Mesolithic era between 11,500 and 7,500 B.C.  Goddess figurine from Chatal Hyuk with lions on each side of her

As explained in the prior chapter, Inanna was part of the death and rebirth cycle along with her lover, Dumuzi, an earlier manifestation of Dionysus, who symbolized the cyclical change between the summer and winter season that lie behind the Easter and Christmas holidays. To the monotheistic Jews, Inanna was the abominable Ashtoreth, or “Lady of Shame.” The author of Revelation refers to her as the “whore of Babylon.” In the Akkadian language of the Epic of Gilgamesh, she is called Ishtar. She would later be known to the Syrians as Sybil, to the Assyrians as Mylitta, to the Canaanites as Astarte or Asherah, to the Egyptians as Hathor, to the Hittites as Shaushka or Ishtar, to the Greeks as Aphrodite, to the Romans as Venus, to the Norse as Freya or Ostara and to the Saxons as Eostre. It’s from this Anglo-Saxon name that we get the name of our own holiday marking the seasonal change of the Spring Equinox. The Easter bunny and the Easter egg are also both rooted in pagan fertility symbolism: the bunny because of its reputation for accelerate proliferation and the egg for it’s association with new birth. Naming the ancient figurines after the Roman goddess of love was not a conscious attempt to link the ancient goddess to the Roman one though. The name stuck after it was first used by the Marquis Paul de Vibraye in 1864 under the name Venus Impudique, or “Immodest Venus,” to describe a heavily damaged and particularly slimmer-looking goddess statue made of mammoth ivory. It was meant to be an ironic reference to the term Venus Pudica, or “Modest Venus,” a term used to describe a classic pose in Western art in which a nude female keeps one hand covering her private parts. This was made to contrast the unashamed depiction of the feminine anatomy on the ancient figurines with that of the more modern “modest” portrayal in western art. The pose, however, that of hands holding or covering the breasts, is comparable. If it’s possible to trace the fertility goddess from prehistory to the Sumerians, Canaanites, Hittites, Greeks, and Romans, the name may have been more appropriate than the Marquis had imagined.

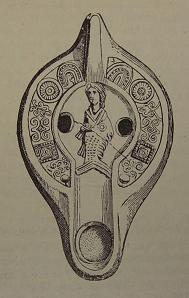

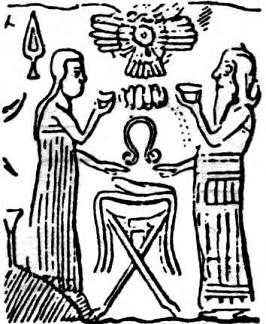

Eve and Adam Now we move from the earliest unknown religion to earliest known religion. Long before the earliest parts of the Bible were first brushed in the Levant, tales of gods and heroes was wedged into clay by Sumerian scribes living in ancient Iraq. The archaeological finds of the modern age have allowed us to look further back than into history than ever before, uncovering the myths of archaic gods from ancient libraries long buried by the sands of time. Certainly there were a great multitude of adventure stories before those of the Sumerians, but they had the misfortune of not having been written down and locked away for three millennia beneath the earth. Even the existence of the Sumerians has only been known for the past 150 years, having been forgotten for thousands of years. In ancient times, Iraq made up the eastern pinnacle of the Fertile Crescent, a moon-shaped patch of vegetative paradise in contrast to the harsh desert life that comprises most of the Middle East. The Sumerians appeared in southern Iraq somewhere between 6,000 and 4,000 B.C., calling themselves the Emegir: the “black-headed people” (or possibly “bald-headed people“). The name Sumer came from a word used by the Akkadians and later Babylonians to describe the area in southern Iraq where the Sumerians lived. They were either replaced or are descended from the Ubaid culture, which thrived between 5900 and 4300 B.C. The Ubaid culture was the first known to have used the wheel, the sail, advanced irrigation techniques, and a monetary system made out of clay tokens. They were in turn preceded by two contemporary cultures: the Halafian culture, which was ruled by rich chieftans, and the Samarra culture, whose people used large scale irrigation. Both of these cultures replaced the already 500-year old Husunna culture around 6000 B.C., and were in turn absorbed by the Ubaid culture some 500 to 600 years later. The Husunna culture lived on the Iraqi/Syria/Turkey border where Assyria would later make it’s capital. They grew barley, bred farm animals, smelt copper, and were the first to create the stamp and painted pottery. The first towns and temples were built around 5,000, during the Ubaid period. By 4300, copper was bring worked and the first cities were being built. The Sumerians had arrived by 3400 and were pressing pictographs of simple objects into the wet clay using reeds, and even then it was already a complex system with over 700 symbols. Around 2900, this pictography was simplified into a more abstract wedge-shaped cuneiform language that came to be used by their eastern neighbors of the Indus Valley in India. Some of their phonetic seedlings have even survived 5,000 years of linguistic evolution and jumped over to our Indo-European branch of languages. For instance, the word ‘alcohol’ is rooted in the Sumerian word for eyeliner, ‘kohl,’ and the scientific name for the marijuana plant, Cannabis, dates back to the Sumerian word ‘kanubi,’ meaning ‘cane of two [sexes].’ Our word for a watery void ‘abyss’ also seems to stem back to Sumer through the word ‘abzu,’ the underwater home of the Sumerian god of wisdom, Enki. The Sumerians were also the first to divide the circle into 360 degrees and to organize the day into 24 hours of 60 minutes, associating the number 60 with the head of their pantheon, An, whose name means “Heaven.” Geometry was especially important in their astrology, which was based on the sun, the moon, and the five visible planets. From what we know of them, the Sumerians seem to have contributed more to the ancient world in culture and technology than the Greco-Roman world did to Western Europe. The Sumerians practiced slavery, but it was one based on economy rather than heredity, and a condition that one could buy oneself out of. Prostitution was common and Sumerian men could have concubines, but only one wife. Marriages between slaves and freemen were common. Divorce was legal but uncommon, mostly granted due to the inability to conceive a child, and adoption was popular for the sake of continuing one’s namesake. Children were required to show respect to their parents and elder siblings or face disinheritance. The culture was patriarchal. Only men were educated and all but one of the Sumerian rulers listed on their king lists were men. Wealthier families could send their sons to school to study economics, administration, and creative writing, so as to become a scribe for the local temple or palace. There is also some evidence to suggest that before 3,000 B.C., the average Sumerian was a naked field worker. The Sumerians wrote many things on their tablets: lessons for schools, trade agreements, accounting, but the heart of the culture we can construct comes from their mythology. It is from the stories of gods and men that we see how the first men who lived in cities pictured their role in the universe. Like the majority of ancient civilizations that came after them, they believed in a pantheon of gods, one nearly identical to the future Babylonians and Assyrians, and which bore strong relationships with the religions practiced in the Indus Valley (India), Canaan (Palestine), Haitia (Turkey), Greece and even the Norse lands. Each Sumerian city-state had a temple that owned about two-thirds of the land and was dedicated to one of the gods of the pantheon, which acted as a king or mascot for the city. Uruk, which hosted the largest population of the area and was home to the ancient hero Gilgamesh, was dedicated to An, the king of heaven. Uruk is located on an abandoned channel of the Euphrates river about 155 miles south of Baghdad. Although Uruk is believed by many people to be the source of the name of Iraq, little was known of it until it was excavated by German archaeologists starting in 1912. The ancient site was not abandoned by the people so much as the Euphrates itself, the river having changed course since those ancient times. The Sumerians also had mythical timelines, in which each city’s dynasty was divided into different dynastical periods, each concluded with the capital of the dynasty being conquered by a different city. After this, the kingship was said to have been “brought to” the capital of the new dynasty, until that city was attacked and kingship was brought somewhere else. Uruk, Ur, and the Akkadian city of Kish were the greatest competitors, with each of them taking kingship at least three times, according to the king lists. Even though the Akkadian city of Nippur was never the capital of a dynasty, it was also important because no king was considered legitimate unless it was sanctioned by that city. Nippur is also where 80% of all the excavated Sumerian literature has come from. That city was dedicated to Enlil (“Lord-Air”), the son of An (“Heaven”) and Ki (“Earth”). It was believed that in distant ages past, heaven and earth were one entity called “An-ki,” but after Enlil was born, he took mother earth away for himself, and the two became separated. In those days, the gods walked the earth like men. During that time Enlil lived in the city of Nippur along with his future wife Ninlil (“Lady-Air”). In the Sumerian myth, Enlil and Ninlil, Enlil was banished from Nippur by the rest of the gods for impregnating Ninlil, and travels to the underworld. The reason for his banishment seems to be because Ninlil is too young, but one interpretation I would suggest is that the inclusion of male god into the pantheon through “marriage” may have originally met with fierce resistance. When Ninlil follows Enlil there, he impregnates her three more times in the guise of three netherworld entities: the gatekeeper, the river man, and the ferry man (equivalent to Charon, the ferryman of the river Styx in Greek mythology). Ninlil gives birth to three netherworld gods, including Nergal, the future husband of the Queen of the netherworld, Ereshkigal. These three gods remain behind as substitutes, allowing Enlil, Ninlil, and their first son, Suen, the moon god, to return. According to Sumerian myth, Suen would later marry Ningal, who in later Phoenician inscriptions is identified as a sun goddess. She would give birth to twins: Utu, a sun god identified with laws and justice, and Inanna, the fertility goddess who was probably associated with the moon due to it’s connection with the calculation of months and the menstrual cycle. Sumerian mythology says that kingship began in Eridu, which was the city of Enki (“Lord-Earth” or “Lord-Mound”), the god of wisdom who lived in the abyss. Archaeological evidence confirms that it is one of the earliest Iraqi settlements, going back to 4,000 B.C. This does not mean it was really the first city to be built, as the Sumerians believed. The oldest city in the world is today generally believed to be Jericho, whose settlement in Palestine was inhabited by the Natufian culture some time before 9,000 B.C. According to the historian Dr. Gwendolyn Leick, Eridu’s earliest levels show signs of three different ecosystems: the mud brick houses and canals of the afore-mentioned Samarra culture, the reed huts and shore-dumps of Arabian fisher-hunters, and the constructions of nomadic sheep and goat herders from the desert. The city was centered around Enki’s temple, the “House of Abzu,” which was on the edge of a swamp and was built within a depression that allowed water to accumulate around it. This abzu was thought to be an freshwater ocean that existed below the ground, feeding all the lakes, rivers, springs, and wells of the land. In the story of Enki and Ninmah, it is Enki who is said to be the father of all the elder gods instead of Uruk’s god, An. Enki is said to have been sleeping beneath the ocean when the lesser gods who were dredging the clay began a revolt. He is woken by his mother, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval oceans and mother to all the gods. In later Babylonian times Nammu became identified with the multi-headed dragon Tiamat, who the god of Babylon Marduk slew, just as Yahweh is said to have slain the multi-headed male dragon Leviathan. In this earlier Sumerian story, Nammu plays a far more positive role, telling Enki to take the earth goddess Ninmah and create a helper for the gods so that they would no longer have to work. Ninmah (“Lady-Exalted”), who was also called Aruru and Ninhursag (“Lady-Mountain”), had a separate temple in Eridu named “House of the Sacred Goddess.” Enki and Ninmah make humans out of clay, similar to how Adam is formed in Genesis (2:7), but after getting drunk, Ninmah began to make some people with physical deformities. Enki countered each of the physical deformities with a fate, that is, a job that they could do, such as making the blind man a musician and giving the eunuch the job of standing before the king. Enki then tries to form a man and have Ninmah make a fate for it, but creates one so badly deformed that it greatly distresses the goddess and nothing can be done for it.  Enki and Ninmah The ending seems to resonate with an aura of compromise in theological duties between the older fertility goddess cult and the new sea god cult. The association with the feminine religion with serpents also resonates through Greek mythology in the likes of: Typhon taking revenge against Zeus for his mother, Gaea; Jason’s x-wife Medea, a worshipper of the goddess Hecate, who killed her sons before escaping on a cart pulled by dragons; and Perseus slaying the snake-haired gorgon Medusa. Although Medusa was originally said to have been born the way she appeared, the Greek poet Ovid changed her origin to having being a beautiful nymph before being cursed by the sea god Poseidon after making love inside his temple, a suitable parallel to the hieros gamos ceremony. Another story, Enki and Ninhursag, describes how Enki laid down with his spouse in the virgin land of Dilmun, a pristine paradise where there was no pain or aging, where “the lion did not slay, the wolf was not carrying off lambs.” This brings to mind the description of an Eden-like future where “the wolf will live with the lamb, and the leopard will lie down with the young goat.”, the Book of Isaiah describes (11:6). Isaiah’s vision of a New Jerusalem is similarly described as a place of no weeping and crying, where everyone could live a long life (65:19). Enki then told Utu to purify the pools of salt water and turn them into fresh water, and the sun god caused fresh water to rise up from the ground, similar to how “streams came up from the earth and watered the whole surface of the ground” in Genesis (2:6). Enki then lies with Ninhursag in the swamp and they conceive a child named Ninsar (“Lady-Plants”). The labor lasts nine days instead of nine months and the delivery is painless. This is consistent with Genesis in which there are no labor pains until Hawah, or Eve, eats the fruit of wisdom of good and bad (3:16). Enki then conceives a daughter with Ninsar, who gives birth to Ninkurra (“Lady-Mountains”), and when Enki conceives a daughter with Ninkurra, she gives birth to Uttu, who might be a spider goddess of weaving. Enki then lies with Uttu, but when she begins to feel pain within her, Ninhursag takes Enki’s semen out of her and uses it to grow eight plants. Enki later comes by and sees the plants, and gives them each a fate, but eats them in the process, which causes Ninhursag to curse him, saying she will not give him the “life-giving eye” until his dying day. This calls to mind the curse that God pronounces on Adam and Eve for eating the fruit (3:14). Ninhursag then disappears, and Enki becomes very ill, causing all the gods to sit down in the dust and despair. A fox offers to find her if Enlil will have two standards of him to be erected in the city. The fox finds her and tells her how all the cities are suffering, so Ninhursag rushes back to find Enki in great pain. When asked where it hurts, Enki names eight parts of him that are in pain, and so Ninhursag gives birth to eight healing deities for each part. When Enki mentioned that his ribs hurt, she gives birth to Ninti, which can be translated “Lady-Rib” or “Lady-Life,” since the Sumerian word “ti” can mean both “rib” and “life.” In Genesis, Eve is formed from one of Adam’s ribs (2:21) and Adam names his wife Hawah because she is “the mother of all living” (3:20). Even though the word for “rib” in Hebrew is different than the word for “life,” it appears that the Sumerian association made between the two words continued on into Hebrew culture. According to the Sumerian king lists, the first king of Eridu was Alulim, who ruled for 28,000 years. In later times, Alulim was said to have had an advisor named Adapa, whose name, like Adam, means “man.” The Myth of Adapa has been found in both the Armana tablets of the monotheistic pharaoh Akhenaton (1300’s B.C.), and in Nineveh library of King Ashurbanipal of Assyria (600’s B.C.). He was also known to the Kassites and the Babylonians. The tablet begins by saying, “Ea made broad understanding perfect in Adapa, to disclose his design of the land. To him he gave wisdom, but did not give eternal life.” A Babylonian priest named Berossus reinvigorated interest in the figure during the 200’s B.C., using the name of Oannes, a corruption of U-an, another name of Adapa’s. Written in the Semitic language of Akkadian, the name of Enki is changed to Ea, which in the Sumerian language was the name of his temple (E-a, “House of Water”). Adapa is referred to as an abgallu, or “water-great-man,” and a sage descended from the gods. He is often listed as the first of the famed “Seven Sages” who brought civilization, arts, and crafts to humankind. The theme of the “Seven Sages,” which first appears in Sumerian texts, would resonate in Hindu, Chinese, and Greek myth, although who these sages were identified with were completely different. So, instead of being the first man, Adam appears to have been the first priest and exorcist of Eridu, and is depicted as wearing a giant fish costume. Depictions of priests in fish garb is common in Sumerian carvings and statues. The image is very similar to the image of a man inside a fish on a Christian oil lamp from the 200’s A.D. The picture appears in Joseph Campbell’s book, The Masks of God: Creative Mythology.

The myth tells how Adapa was fishing out on the lake one day when the South Wind blew his boat over. Angry at the South Wind, he cursed the great wing, causing it to break, and no wind blew for seven days. This comes to the attention of Anu (the Akkadian name for An), and the god of heaven rose up from his throne, crying, “Heaven help him!” When Anu called Adapa to be brought before him, Ea dressed Adapa in clothes of mourning and bedraggled his hair so as to appear unkempt. He then told Adapa that when he went up to the gates of heaven, he would meet the gatekeepers, Dumuzi and Gizzida, and that he should tell them that he was in mourning for two gods who had left the country. When the gatekeepers asked who those gods are, he was to pretend not to know who they were and say that they were Dumuzi and Gizzida, which would give them a good laugh and ensure that they would give Anu a good word for him. One might say it’s the equivalent of Adam becoming friends with the Babylonian Jesus in order to get on God’s good side. The character Gizzida was based off of a hero from the city of Ur named Ningishzida, who in an older Sumerian story is forced by a galla demon to take a ship to the netherworld as he tries unsuccessfully to convince his “sister,” Ama Shilama, not to come with him. In the Myth of Adapa, Ea also warns Adapa that if Anu gives him any bread and water that he should not eat it because it would be the bread and water of death, but if they offered him a garment and anointing oil, he should accept. Adapa then travels to heaven and tells Dumuzi and Gizzida that he is mourning for them, and true to Ea’s word, they laugh and later give Anu a good word for him when Adapa explains himself. When it comes time for Anu to decide what to do with Adapa, Anu grew quiet and then said, “Why did Ea disclose to wretched humankind the ways of heaven and earth, [yet] give them a heavy heart? It was he who did it! What can we do for him? Fetch him the bread of eternal life and let him eat!” God essentially blames man’s weakness on “the devil” and decides to give him eternal life. But when the bread and water are given to him, Adapa took Ea’s advice and refused to eat. Although Adapa accepted Anu’s garment and allowed himself to be anointed, Anu laughed and asked, “Come, Adapa, why didn’t you eat? Why didn’t you drink? Didn’t you want to be immortal? Alas for downtrodden humans!” Adapa explains that Ea told him not to and he is then taken back to earth. Although the rest of the myth is fragmentary, his actions seem to have resulted in a great amount of disease and violence on the earth. The myth shows clear parallels with the Fall of Man as described in Genesis. The image of the snake who cheats Adam out of immortality seems to come from the dragon image which is associated both with Enki’s mother Nammu and his son Dumuzi, but there are other myths that associate a snake stealing eternal life. The image of the fish may also be related to the early Christian symbol. Jesus has had a long association with the Eden story and is often referred to as the Second Adam. In the Epistle to the Romans, it is said that Jesus’ death overturned the sin of Adam, bringing eternal life to humankind (5:12). There is also a tradition in which Jesus was crucified directly over the bones of Adam, from which the place is believed to have derived it’s Aramaic name, Golgotha, meaning “Place of the skull,” as opposed to “Place of the skulls.” This tradition survives in Christian art in the form of a skull and bones lying at the foot of the crucifix. When Adam’s son Cain is exiled, he travels east of Eden to the land of Nod, land that means “wanderer.” Cain is said to have built the first city, naming it after his son Enoch. This implies that Cain was the first king (the Sumerian Alulim). When Cain laments that he will be killed, God promises a curse will be given to anyone who kills him. This is perhaps a reference to the ancient belief that anyone who killed a king would be cursed (4:15). Although Cain’s son Enoch is largely believed to be a different Enoch than the one who was taken up to heaven in Genesis (5:24), there is reliable evidence that the abundant repetition of names in the genealogies throughout the first five chapters of Genesis came about through the combination of different source texts. As such, the name U-an may also be the basis for the Biblical Enosh, since one source from Genesis, not the earliest, says that Adam had a third son named Seth, whose own son was named Enosh, thus providing an Jewish “alternate” for U-an (4:26). Like Enoch, Adapa is said to be a sage who brought the knowledge of civilization to humankind, but in sharp contrast, Enoch gains immortality instead of loses it. The Book of Enoch in fact divides this entire concept of “divine wisdom” into two parts: immoral wisdom taught by Samyaza, Azazel, and the fallen angels, and elect wisdom, which Enoch brings down from the heavens to pass on to later generations. The dualism is indicative or the era in which Enoch is believed to have been written, with pre-Essene forms of Judaism being heavily influenced by Persian Zoroastrianism. A version of the Cain and Abel story has also been found in the Sumerian texts, only in the form of gods instead of men. In the story of The Debate Between Winter and Summer, Enlil copulates with the hills of the earth and fathers Emesh (“Summer”) and Enten (“Winter”). Enlil fated that Summer would found the towns and villages and work the land with oxen while Winter shaped the lagoons and dealt with the spring floods. Winter also creates the fish of the sea and the birds of the sky in one instance, similar to how God creates fish and birds on the same day before land animals were formed (1:20). Summer in turn builds the first city, just as Cain is the first city-builder (4:17). Like Cain and Abel, they both go and sacrifice to Enlil. Summer brings mostly animals to the sacrifice while Winter brings mostly birds, fruits, and vegetables, and they soon get into argument over which sacrifice is better. At first Winter is too tired from working to argue but then, overcome with anger, he ‘reared himself’ and told his brother that all of Summer’s harvest had come from Winter’s toil. Summer countered that all of the straw that Winter hauled got thrown into the hearth because of the cold that Winter brought. The argument comes to a quick stop when Enlil appears, and Summer praises Enlil, saying that as long as he is there, there is harmony and respectful awe with the people. Enlil settles the argument by saying, “Winter is controller of the life-giving waters of all the lands -- the farmer of the gods produces everything. Summer, my son, how can you compare yourself to your brother Winter?” At this, Summer bowed his head to Winter, saying a prayer for him, and a banquet is prepared with beer and wine. Summer presents Winter with gold, silver, and lapis luzili, and the two of them “pour out brotherhood and friendship like best oil.” The ending is in stark contrast to the Genesis story, of course. Where the appearance of Enlil brought peace between the two brothers, Yahweh’s upbraiding causes Cain to become jealous and commit the first murder. And in the Sumerian story, even though Summer’s “herdsman” sacrifices are better, Winter’s “farming” sacrifice is found to be more pleasing because he worked harder for it. In Genesis, Cain brings fruit from the soil, and Abel sacrifices of the firstborn of the flock and it’s Abel’s “herdsman” sacrifice that God favors. The reason for this is not surprising if we consider the background of the Sumerians against the Hebrews. The Sumerians who wrote this story were far more dependant on the farming culture of the city. The Hebrews were in turn a largely pastoral community, whose sacrifices were almost entirely made up of sheep, goats, and calves. The duality between farmer and herdsman qualities of Cain and Abel are also elaborated upon in the apocryphal Book of Jasher, which has Cain complaining about Abel’s sheep grazing over the land he was trying to plough. Abel points out that Cain used the meat and wool from the sheep, and so unless he wanted to give those up, he should allow the sheep to graze on his land. So Cain asks him, “Surely if I slay you this day, who will require your blood from me?” Abel answers that God will avenge his cause and require his blood from Cain. Cain’s anger flares and he kills him with, of all things, an iron ploughing instrument. Immediately regretting it, he weeps and buries Abel, and God curses him to wander the earth. When the twins of Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus, were arguing over where to build their city, they agreed to augur a “competitive sacrifice” as well, one in which each took a seat on the ground next to each other. In a vision, Remus sees 6 vultures (or eagles), but Romulus sees 12, and Remus becomes enraged at the victory. Remus ridicules and obstructs his brother’s work building the trench for the new city, and then jumps over it to prove how easy it could be traversed. For transgressing his boundary, Romulus kills Remus on the spot and decides to name the city after himself, Rome. Just like in Sumerian myth, Rome’s hero was Cain. Flood Epics of the World According to the Sumerian king lists, Alulim and his successor Alalgar ruled Eridu for a total of 66,000 years, after which it was conquered and kingship was taken to Bad-Tibira. Three more kings ruled for another 108,000 years, the last one being “Dumuzi the Shepherd,” who ruled for 36,000 years. Kingship was then taken to the cities of Larag, Zimbir, and finally Shurrupak, until a great flood is said to have covered the entire land. There are several versions of the Noah’s Ark story in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Babylonian mythology, many of them using a different name for the flood hero, but each portray him as the last king of Shurrupuk. The earliest version of the story uses the name Ziusudra, whose name means “life of long days,” as he is said to have lived 36,000 years. In the Sumerian text, Instructions of Shurrupak, Ziusudra is identified as the son of Ubara-Tutu, the last king of Shurrupak mentioned in the king lists, whose name means “friend of Utu.” The oldest Sumerian creation myth, found in Enlil’s city of Nippur, also gives a version of the flood story. Referred to as the Eridu Genesis or the Nippur Tablet, it’s been dated to some time around 2600 B.C. It describes how the Sumerians and the surrounding animals were created by An, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursag to make peace amongst the gods and how kingship descended from heaven to Eridu. The first city is given to Nudimmud, another name for Enki. The second city, Bad-Tibira, was given to the “prince and the sacred one,” probably a reference to “Dumuzi the Shepherd.” The third city, Larag, was given to Pabilsag, another name for Enlil’s son Ninurta. The fourth city was given to Utu, the sun god of justice, and the fifth city, Shurrupak, was given to Ansud, a grain goddess who may be equivalent to Ninhursag and Ninmah. Although the text is heavily damaged, other texts fill in some of the lost details of how human noise caused Enlil to petition the divine court into destroying mankind with a flood. Ziusudra was praying to an idol when a vision came to him and he saw the gods planning the great deluge. Enki then tells Ziusudra to build an ark. Just like in the flood of Genesis, and in the later flood stories in the epics of Atra-Hasis and Gilgamesh, the storm is said to have raged for seven days and seven nights (7:12). Ziusudra then drills a hole in the ark, just as Noah did (8:6), so that the sun god Utu shone his light inside the ark. When Ziusudra stepped out of the ark onto dry land, he kissed the ground before him, and like Noah, sacrificed a burnt offering, which was enjoyed as a “sweet savor” by the gods (8:20). Although Enlil is at first upset at what Enki did, Enki convinces him to not only let Ziusudra live, but to give him immortality, and to live on Mount Dilmun, “the place where the sun rises.” The afore-mentioned Babylonian priest Berossus, who identified Ea, or Enki, with the Greek god Kronos, the titan of air and time, and said that the ark of “Xisuthros” could still be found in the Gordian Mountains of Armenia during his own time (200‘s B.C.), and that pilgrims would go there to scrape asphalt from the ark’s remains and use it for witchcraft. The Gordian mountains are east of the Ararat mountain range in Turkey, where Genesis places Noah’s ark, but which also has been referred to as “Ararat.” It’s also north and slightly west of Sumer, not east, as the Eridu Genesis suggests. Even some 300 years later, Josephus wrote that Noah’s ark was on display for anyone to see. A very strange rock formation shaped like a giant ship was discovered in 1948 on a mountain range known as Durupinar near the Iranian border in eastern Turkey was discovered in 1948. It was surveyed in 1960, and after two days of digging and dynamiting, was declared to be a freak of nature. It was “rediscovered” in 1977 by the self-styled archaeologist and explorer Ron Wyatt. He was joined in 1985 by David Fasold, who used a radar to detect iron in what he believed was in the formation of the upper deck of the ark. In his book, The Ark of Noah, Fasold also argued that the Great Pyramid of Giza was built by Noah’s son, Shem, in 2500 B.C., at the exact center of the earth. After further drillings and excavations, Fasold accepted the conclusions of Lorence Collins in 1996 that the formation was only a curious upwelling of mud. Even so, Fasold believed it was that formation that ancient people like Berossus and Josephus took to be the ark, although he changed his mind again shortly before his death in 1998. There has yet to be conclusive evidence of what the formation is.  Durupinar site in Eastern Turkey, believed by some to be the remains of Noah’s Ark The flood story that appears in Genesis is derived from two different sources. The earliest source was written by an author that scholars refer to as the Yahwist, or “J,” because he refers to God by the divine name Yahweh. This is the author to wrote the majority of Genesis, and is denoted in brown. The second source is referred to as the Priest, or “P,” because he is believed to be an Aaronid priest, that is, a priest descended from the high priest Aaron. The Priest is responsible for all of Leviticus as well as large portions of Exodus and Numbers, and is denoted in red. As shown in Richard Elliot Friedman’s books, Who Wrote the Bible? and The Bible: With Sources Revealed, two entirely different flood stories can be read out of this combination. The editing to arrange the story into a seamless whole was so well done that it has been largely gone undetected for over a millennia. Yet each source can be read from beginning to end as a complete whole, each with differing details:

“Yahweh saw how great man’s wickedness on the earth had become, and that every inclination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil all the time. Yahweh was grieved that he had made man on the earth, and his heart was filled with pain. So Yahweh said, ‘I will wipe mankind, whom I have created, from the face of the earth—men and animals, and creatures that move along the ground, and birds of the air—for I am grieved that I have made them.’ But Noah found favor in the eyes of Yahweh. This is the account of Noah. Noah was a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time, and he walked with Elohim. Noah had three sons: Shem, Ham and Japheth. Now the earth was corrupt in Elohim’s sight and was full of violence. Elohim saw how corrupt the earth had become, for all the people on earth had corrupted their ways. So Elohim said to Noah, ‘I am going to put an end to all people, for the earth is filled with violence because of them. I am surely going to destroy both them and the earth. So make yourself an ark of cypress wood; make rooms in it and coat it with pitch inside and out. This is how you are to build it: The ark is to be 300 cubits long, 50 cubits wide and 30 cubits high. Make a roof for it and finish the ark to within a cubit of the top. Put a door in the side of the ark and make lower, middle and upper decks. I am going to bring floodwaters on the earth to destroy all life under the heavens, every creature that has the breath of life in it. Everything on earth will perish. But I will establish my covenant with you, and you will enter the ark—you and your sons and your wife and your sons’ wives with you. You are to bring into the ark two of all living creatures, male and female, to keep them alive with you. Two of every kind of bird, of every kind of animal and of every kind of creature that moves along the ground will come to you to be kept alive. You are to take every kind of food that is to be eaten and store it away as food for you and for them.’ Noah did everything just as Elohim commanded him.

By separating the story into two pieces, we can now see two consistent stories where there was once anachronistic confusion. In the J source, it rains for seven days and seven nights, which more closely parallels the pagan versions, while the flood itself lasts 40 days. In the P source, the flood lasts for a full year (370 days). The Yahwist has Noah send out a dove while the Priest has Noah send out a raven, and then the two are combined so that Noah sends out a raven and then the dove twice. P is interested in ages, dates, and measurements, which is where the Book of Numbers gets it’s name, while J is not. The terminology is also different. The Yahwist says everything “died” (7:22), while the Priest says everything “perished.” (6:17, 7:21). As in the rest of the J source in the Bible, Yahweh is far more anthropomorphic than the heavenly Elohim that the P source envisions.

They took the box of lots

The Greek writer Apollodorus, writing from the 140’s B.C., said that after Zeus and the Olympian gods had triumphed over the Titans, they also threw dice to determine what elemental power they would rule over. Zeus won the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Pluto was given Hades. There is even mention of a division of lands made in ancient times in the Torah. As mentioned in the first chapter, the Dead Sea Scroll version says that the land was divided by the “Most High” according to the “sons of Elohim,” and that “Yahweh’s portion is his people, Yah-Akov,” or Jacob, whose namesake was Israel (32:7). The original passage was undoubtedly altered because it portrayed a more Henotheistic outlook, in which the God of Israel is not the highest god. Rather, it looks more like the Sumerian model, in which the Most High (Anu) gives commands from heaven while Elohim (Enlil) executes them on earth, and that the sons of Elohim rule over their respective states. It implies that Israel was given to Yahweh, Moab was given to Chemosh, and Babylon was given to Marduk.

‘You are the womb-goddess, to be the creator of Mankind!

The god chosen to be sacrificed is Gesthu-E, “the god who had intelligence.” He was slaughtered in their assembly and his flesh and blood were then mixed with clay and the spittle of the Igigi, and the human spirit was created. Nintu then proclaimed that “the ghost existed so as not to forget the slain god.” She then appeared before the Igigi and told them that she had relieved them of their hard work and had bought their freedom. The Igigi then threw themselves down and kissed her feet, saying, “We used to call you Mami, But now your name shall be Mistress of All Gods.” Enki and the “wise Mami” then enter the “Room of Fate” where 14 “womb-goddess” are assembled. Enki then took the clay and Nintu recited an incantation. She then pinched off 14 pieces, setting seven to the left and seven to the right. She cut their umbilical cords with a reed and then called up the wisdom of the womb-goddesses to create seven males and seven females. She then made certain rules concerning birth, such as a woman was to cut her own baby’s umbilical cord, mud brick would be set down in celebration, and a man and woman can first choose each other when a beard could be seen on the man’s cheek. The womb goddesses counted out ten months, not nine, and Nintu slipped her staff into the womb and was happy to find the humans fully formed. She then performed her celestial midwife duties and delivered the 14 humans. After that, she decreed that whenever a baby is born, the midwife should celebrate in the house of the Qadishtu priestess, Inanna’s temple. When the wedding bed is laid out in the house, Inanna would rejoice in the marriage and a wedding celebration was to take place at the father-in-law’s house for nine days.

The progeny of Adamis and Hevas soon became so wicked that they were no longer able to coexist peacefully. Brahma therefore decided to punish his creatures. Vishnu ordered Vaivasvata to build a ship for himself and his family. When the ship was ready, and Vaivasvata and his family were inside with the seeds of every plant and a pair of every species of animal, the big rains began and the rivers began to overflow.

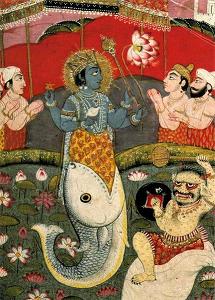

The Matsya Purana, or “Fish Chronicle,” is the considered the oldest of all the Hindu texts, possibly dating back as far back as 300 A.D., and is believed to have first been recited by Vishnu, who like Enki, is associated with the fish symbol. In it, Satyavarman, or Manu, the son of the sun god and king of the world, gave his throne to his son Ikshvaku and went into the forest to meditate for thousands of years. Brahma then told him that he could have anything he wishes and he asked that he be allowed to save the world at the time of it’s destruction. Days later, he was washing his hands in a stream when he accidentally pulled out a minnow, and put inside a waster pot. As the fish grew and grew, it was moved to a jar, a well, the river Ganga, and then finally the ocean. Finally, the fish revealed that he was the god Vishnu and that there was going to be a great flood. Satyavarman, whose name means “Protector of Righteousness,” was to build a ship and tie it to the fish’s horn. The fish then disappeared and for hundreds of years there was a great famine, similar to the one that preceded the flood in the Epic of Atra-Hasis. After the sun burnt the land into ashes, dark clouds began to form and the rains poured down until there was a great flood. Satyavarman’s ship was tied to the fish’s horn, and while the fish pulled them along, Satyavarman asked Vishnu about the creation of the world. Vishnu explains that in the beginning there was only darkness, until Vishnu removed the darkness and split himself into three forms: Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva. This may be a reference to the fact that Enki seems to have been the first god and that Anu and Enlil seem to have been added later. Like Enki, Vishnu slept in the water until a golden egg that shone with the light of a thousand suns began to form out of his navel. After a thousand years, the egg cracked, and Brahma emerged. One half of the egg formed the heavens while the other half formed the earth, similar to how the birth of Enlil was said to have split the heavens and the earth in Sumerian myth. Brahma began to meditate and the Hindu scriptures known as the Vedas came into his heart and was distributed by him. Ten sages were born directly from him, followed by the first man and woman who could procreate on their own. Brahma asked Shiva to create also, but Shiva created only immortals like himself.  The incarnation of Vishnu as a fish, taken from a devotional text In Greek mythology, Prometheus is the god of wisdom, who like Enki, forms humans from clay, inadvertently introduces civilization to them, and then warns the Greek Noah of the great deluge. There was a cult to Prometheus known to have existed in Athens as well as three other main cities in central and southern Greece. Prometheus was the nephew of Kronos and the son of the titan Iapetus, who has long been equated with the Biblical Japheth due to their names being nearly identical when translated. Although Prometheus was a Titan, he is said to have joined Zeus’ side when Zeus rose up against Kronos. Although there are generally said to be five Titans, Kronos and one Titan for each corner of the earth, the Sibylline Oracles (dated between 100 and 400 B.C.) make Iapetus to be one of three brothers, along with his brothers Kronos and “Titan.” Kronos was associated with Saturn, as was the much earlier god, Chronos, a personification of time used in pre-Socratic philosophy. Although Chronos and Kronos were associated with one another since Hellenic times, their etymological roots may be completely different. Chronos is the Greek word for time and he is said to be the father of the three goddess of the seasons, the Horae. He was also known as Aeon, a word used by Gnostics to describe the angel-like emanations of God, or in the oneness of God, such as the name Aion teleos, which means “Perfect Aeon.” Kronos was the god of air and time and king of the Titans until his son Zeus overthrew him, fulfilling a prophecy that had caused Kronos to eat his children in order to stop it from happening. The name Kronos may be related to krounos, the Greek word for Spring, or from keras, which means horn. In this way he may have been equivalent to the Celtic horned god from around the 300’s B.C. in Europe, and even without this link he can certainly be associated with Enlil and El the Bull. A carving of the horned god with a Parisii inscription discovered in France gives the name of this horned god as “[C]ernunnos,” but the first letter had been scraped off. The letter C has been reasonably substituted because carnon or cernon means “antler” or “horn” in Gaulish, which goes back to the proto-Indo-European root *krno, from which the Latin word for horn, cornu, and the Germanic *hurnaz comes from. The name may also be related to the evil god Kroni, who in Ayyavazhi sect of Hindu mythology is said to have gone on an eating rampage that was going to threaten the entire universe, similar to how Kronos eats his children. Mayon, another name for Vishnu, is said to have appeared in six different eras in order to slice Kroni into six different pieces and save the universe. As mentioned in an previous chapter, the Roman festival of Saturnalia was replaced by the birthday of Sol Invictus in the 200’s A.D. and then by the birthday of Jesus in the late 300’s. In Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Prometheus fashions humans out of clay, into the form of a god, by the command of Kronos. Another Greek myth says that the task of giving survival traits to all the creatures of the earth was given to Prometheus, whose name means “Forethought,” and his brother Epimetheus, whose name means “Afterthought.” Epithemeus convinces Prometheus to allow him to give out the abilities. Epithemeus gives some creatures the ability to fly, some the ability to eat grass, and to others strength, the ability to live underground, or to resist cold and heat, but when he gets to man, he finds out that he has run out of survival traits. Seeing how men suffered in the cold, Prometheus steals fire, as well as all the other arts of civilization, from Haphaestus, the volcanic god of the forge, and Athena, the goddess of wisdom who sprang out of Zeus‘ head, and gives these powers to mankind. Zeus is outraged by humankind becoming enlightened and pronounced that Prometheus would be bound to a rock on Mount Caucasus for all eternity, forced to watch Zeus punish man for his misdeeds. Every morning his liver was to be torn out by an eagle every morning and because he was a god, the liver would grow back the next day. This has caused some people to question whether this myth showed that the Greeks knew that the liver is one of the few human organs that can regenerate itself. Mount Caucasus was considered to be one of the pillars of the world in Greek mythology, and is the area from which the racial designation “Caucasian” was derived in the 1800’s A.D. The word hubris, has been used to describe the sin of Prometheus as well as that of the devil. The word is normally translated as pride, which is often referred to as the devil’s favorite sin, and comes from the Greek word hybris, meaning violence or presumption against the gods. Aristotle defined it as the pleasure of thinking that treating others poorly increases one’s own superiority. Zeus then tells Haphaestus to mix the “loveliest, sweetest, and best” with the opposite of each. So Haphaestus mixed gold with refuse, wax with fliny, pure snow with highway mud, honey with gall, rose bloom with toad venom, laughing water with peacock squall, the sea’s beauty with the sea’s treachery, the fidelity of the dog with the inconsistency of the wind, and the mother bird’s heart with the tiger’s cruelty. With this substance, he formed the beautiful Pandora, the first woman, whose name means “all-gifted.” Zeus breathes life into her, similar to how Adam has life breathed into him (2:7), and Pandora is given as a bride to Epithemius. Although Prometheus warned Epithemius not to accept anything from the Olympian gods, Epithemius is stricken with love and disobeys him. The two are married and are showered with gifts from the gods, including a box, or more likely, a jar, from Zeus. The jar was not to be opened under any circumstance, but Pandora’s natural curiosity causes her to open the jar, unleashing all the pain and misery of the world (3:6). But when Pandora returns to the symbolic womb, there is still one force left, that of Hope, and she releases it as well. Various myths say that Prometheus was the one married to Pandora, that Zeus tortured Prometheus for the name of the god who would overthrow him, and that Heracles freed Prometheus from his chains, which Zeus allowed as long as Prometheus kept “bound” to a ring of the Caucasus mountain’s rock, thus fulfilling his literal command that he be “bound” to that rock forever. This “Sympathy for the Rebel” of Prometheus-adoring writers might be compared to Gnostics who reread the snake in the Garden of Eden as a heroic figures. Epithemeus and Pandora had a daughter named Pyrrha, the first mortal who was born, and namesake of the Greek country of Thessaly. Prometheus fathered the Greek Noah, Deucalion. Deucalion’s mother was either Clymene, an Oceanid who was also Prometheus’ mother; or, according to Herodotus, Asia, who is popularly identified with Clymene; or, according to Hesiod, a goddess named Pronoia, who is otherwise unknown. In Sumerian myth, Enki’s mother Nammu is also his father An’s mother, and the mother to his son Dumuzi is named Damkina, another earth goddess often associated with Ninhursag, Ninmah, Nintu, and Nammu. In the Greek play, Prometheus Bound, written by Aeschylus in the 300’s B.C., Prometheus says, “My mother, Themis, or Gaia [Earth], one person, through of various names.” Deucalion himself is said to have married Pyrrha, the daughter of Pandora. In some versions of the story, Pyrrha would have a daughter who was also called Pandora, and she would become mother of Graecus, father of the Greeks, and Latinus, father of the Latins. Although there is no surviving myth of Deucalion creating wine, his name means “New wine sailor,” which brings to mind both the story of Noah being the inventor of wine (9:20) and the “new wine-flasks,” as spoken of in the Gospel of Mark (2:22), or the wine of the New Covenant in Luke (22:20). Acts has the apostle James decree that Gentiles need only follow laws very similar to the laws of Noah (15:20). In one of the Hindu flood myths, Deucalion is referred to Dyaus-Nahusha, and it has been suggested that this is possibly the origin of the name Dio-Nysus, the Greek incarnation of Dumuzi. The invention of wine, which was traditionally credited to Dionysus, could be seen as symbolic of fertility in the context of Deucalion’s preservation of all life. Pausanias, a Greek traveler and geographer from the 100’s A.D., tells a Laconian version of the Dionysus myth in which Dionysus and his mother Semele are locked into a giant chest and cast into the sea by Semele’s father Cadmus, who does not believe Semele was impregnated by Zeus. Instead of being killed by Zeus’ true image, Semele dies on the ark before it wanders to Laconia, in southern Greece, where Dionysus is adopted by her sister Ino. In a large Byzantine historical encyclopedia dated to the 900’s A.D., known as the Suda, there is a quote from Prometheus saying, “According to the Judges of the Judaeans, Prometheus was known amongst the Greeks [as the one] who first discovered scholarly philosophy. He it is of whom they say that he molded men, inasmuch as he made some idiots understand wisdom. And Epimetheus, who discovered music.” The reference may refer to the duality of the Apollonian reason and Dionysian music, or perhaps the twin motif in Genesis to the sons of Lamech: Jabal, the father of tent dwellers and livestock, and Jubal, the father of harp and flute players (4:21). In the story of Deucalion‘s ark, Zeus decides to bring the flood because he was disgusted by the cannibalism and human sacrifice that he saw in Arcadia, in Peloponnese peninsula of Greece, under the guise of being a mortal. He was served the meat of a boy by King Lycaon, and so burned everyone to death in their castle, except for King Lyacon, who he instead turned into a wolf. Zeus also visited the slums where he was served a stew with the remains of the stew-maker’s own brother. Zeus turned them into wolves and restored the life of their brother. Cannibalism is a common trait found in ancient societies, and this may be an ancient criticism of the practice. After destroying the castle with fire, Zeus decided to also create a great flood. So Prometheus instructed Deucalion to build a giant trunk to take refuge in. Zeus overflows the rivers and the trunk is swept away with only Deucalion and Pyrrha in it. The trunk is said to have come to a rest on various mountains in Greece, Macedonia, and Sicily. One myth says that the chest landed on Mount Parnassus and that Deucalion and Pyrrha both gave thanks to Zeus and then found a washed-out temple to the earth goddess Themis. Themis told them that they could repopulate the earth by covering their heads and throwing the bones of their mother over his shoulder. Deuclation and Pyrrha figure out that the their “mother” was the earth and her bones were stones. So they threw stones over their shoulders and created a new race of stone-men that were tougher than the original clay-men that Prometheus had formed. The two of them have their own children as well. They had a son, Hellen, whose name is synonymous with Greek, although he was sometimes called the son of Zeus and Pyrrha. Their daughter was Protogenia, the mother of Opus, Aethlius, and Aeolus; and there was possibly a third child named Amphictyon. In the Finno-Ugaric version of the flood story, centered around Finland, Hungary, and Russia, the sky god Numi-Tarem tries to use a “holy fiery-flood” to destroy the prince of the dead, Kulya-ter. For the gods he built an iron airship, and for the people he created a covered raft. While the sky god builds the ships, he tells his wife to create a new substance called beer, and to bring it to him. He then gets drunk and Kulya-ter overhears Numi-Tarem telling his wife about a flaming deluge. The prince of the dead sneaks into the sewing box of Numi-Tarem’s wife and is able to escape his fate. The gods then fly up as the fiery flood comes, and all but the last seven layers of the raft are burned up. A plague of insects then came along as well, devouring everything in their path. The addition of flame to the flood adds a unique element to this version of the flood story. It could possibly be a reference to the Thera eruption, a huge volcanic explosion in Santorini not far from Arcadia, followed by a giant tsunami. This is also the great natural disaster that is believed to have ended Minoan dominance some time in the Late Bronze Age. After the flood came, it was largely reported in Sumer that kingship descended from heaven to the Akkadian city of Kish, just as it did before with Eridu. According to Sumer and the Sumerians, written by Harriet Crawford, the city of Kish flourished in the Early Dynastic II period soon after an archaeologically attested river flood in Shuruppak that has been radio-carbon dated about 2900 B.C. In 1998, William Ryan and Walter Pitman wrote a book named Noah’s Flood that hypothesized that a cataclysmic flood that turned the freshwater paradise of the ancient Black Sea into a salt water sea around 5600 B.C. was responsible for all the flood stories. However, the evidence for the cataclysmic event itself has been disputed, and nothing about that flood really matches any the details of any of the myths. The Shurrupak flood of 2900, on the other hand, does match the oldest attested versions of the myth in referring to it as a river flood and linking it to a king of Shurrupuk. It’s not impossible that the flood myth is deeper than that, that it was a world myth before 2900, and that the Sumerians simply rewrote it starring King Ziusudra because of his connection to the Shurrupuk flood. But it is this version of the story that would provide the greatest influence on the later Babylonian and Hebrew flood stories. Assuming all the Babylonian, Hebrew, Hindu, Greek, and Finno-Ugaric flood myths are based on this original story, it was not the grandiose size of the flood that made it so famous, but the fact that it swept power away from Shurrupak to the more northern city of Kish. |