Rome Didn't Fall in a Day“The various modes of worship, which prevailed in the Roman world, were all considered by the people, as equally true; by the philosopher, as equally false; and by the magistrate, as equally useful.”

-Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Destroyed by Decadence?

“Decadence” is the first word that comes to mind in almost any discussion on the fall of Rome. Tales of wanton sexual excesses and the orgiastic gorging of food within Roman vomitoriums are often used to explain how something as enduring as the Roman Empire could possibly be laid to waste by German barbarians. The fall of Rome is often pitched as an antithesis for family values, with pornography and homosexuality touted as the hallmarks of modern moral decadence, which as history supposedly shows, will lead to the same decline and fall of the American “empire.” From this frame of mind, it was Julius Caesar who led Rome to it’s highest pinnacle of greatness, with Caligula and Nero bringing Rome into a decadence in society that eventually led to the sacking of Rome by German barbarians and the fall of the Roman Empire. But out of Rome’s ashes arose a new Christian civilization, it’s often said, which spread from the city of Rome to the rest of Europe by way of the great roads the old empire left behind.

Although this fanciful picture is often used to link moral superiority to military superiority, the truth of the matter is that moral and political corruption had been a staple of Roman life from it’s beginning. To make such a distinction between the Rome of the first century and the Rome of the fifth century is to suppose that Rome had not become “decadent” while it’s soldiers raped, pillaged, and burned cities to the ground, it’s citizens routinely left unwanted children exposed to the elements (especially the deformed and illegitimate), and its magistrates forced captured slaves to kill each other in gladiatorial coliseums for the entertainment of bloodthirsty onlookers. Even lining the roads around Rome and Jerusalem with thousands of crucified rebels does not seem to be quite decadent enough for those who try establish connections between religious purity of a nation’s populace and the significance of it’s military power, nor did it incur enough divine wrath to bring about the empire’s end.

Like many other heavily revered figures of the past, Julius Caesar earned his place in the history books by killing a record number of people. In an unprovoked attack on France and Germany, Caesar brought about one the greatest bouts of human misery in his own time. According to Plutarch, the whole campaign resulted in 800 conquered cities, 300 subdued tribes, 1 million men sold into slavery and another 3 million dead on the battle field! After a revolt by the Eburones, Caesar instituted a punitive campaign that saw the complete genocide of the Belgic tribe. Plutarch also told a story in which Caesar is said to have been captured by Cilician pirates. According to him, Caesar joked with his captors; when hearing they would ransom him for 20 gold talents, he remarked that they could net at least 50 for him. After a ransom was paid for his release, it’s said he returned and crucified them all just like he said he would, though the pirates thought he was only joking at the time. This may be a legend based on Pompey, as history records Pompey conducting a campaign against the Cilician pirates as well.

Pompey, who was part of Caesar’s First Triumvirate, went on a campaign to the east, putting down the Mithridates of Iran, Tigrenis the Great of Armenia, Antiochus XIII of Syria, and then moved on to capture Jerusalem. When he blasphemed the Holy Temple by barging in and paying tribute to Zeus, it created an uproar throughout the Jewish world. The Old Testament had always firmly held that no priest could ever enter the inner chambers of the temple. In the apocryphal Book of 3 Maccabees, it’s said that the Egyptian King Ptolemy IV Philopator tried to enter it and was miraculously repelled and then took vengeance on the Jewish population for being humiliated. No magical blockade is mentioned in regard to Pompey, although his salute to Zeus did show a deep seated arrogance in the Roman aristocracy towards the Jewish religion. Pompey and Caesar eventually came to bring war against each other and Pompey was later assassinated in Egypt.

When Caesar’s nephew Octavian showed ingenuity in making it to his camp in Gaul after a shipwreck, Caesar decided to secretly make Octavian his adoptive heir. Octavian repaid Caesar’s kindness by later killing his “step-brother,” Caesarion, the 17-year son of Cleopatra, after annexing Egypt into the Empire. This did nothing to stop him from capitalizing on Caesar’s fame, though. He had purged the Senate, allowing himself to be crowned with the laurel wreath and given the title of “Augustus,” a name that would become synonymous with emperor. The Senate later gave him even more unheard of powers after that, combining the office of Tribune and Censor, after which they handed over to him the title of Pontifex Maximus, or High Priest of Rome.

Although Augustus spent much of his time in drunken revelry with pimps and prostitutes, and would “frequently vomit the remains of yesterday's debauch on the very rostra in the midst of his harangues [speeches],” as the Roman Senator Cassius Dio wrote, Augustus nevertheless saw it fit to pass his own laws on morality. Although the time of Caesar and Augustus were often looked back on as the pinnacle of Roman dominance, traditional Roman values were believed to be on the decline. Just like in modern times, Roman men were also worried about family values, but in their own extreme, barbaric fashion. In 18 B.C., Augustus passed laws encouraging marriage and children, outlawing adultery, and barring celibates from attending public games or gaining an inheritance. The penalty for adultery was banishment, although husbands were allowed to kill their wives or daughters if they caught them in the act. He also enacted the “Law of Three Sons,” which gave greater respect to those who sired three boys. The more populous Rome was, the more soldiers it would have in its ranks.

This appealed to many Romans at the time who believed that their moral decline had started in the 100s B.C., when women and children started gaining more rights and became less dependant on the men. One of the changes that gave women more independence was with the repeal of the Lex Oppia in 195 B.C, a series of laws passed 20 years earlier during the Second Punic War stating that no woman could have more than a half ounce of gold, whether in coin or jewelry. They also disallowed women to wear multi-colored garments or be taken by carriage into the city except during a religious festival. The 100s B.C. had seen a shift in their ancient patriarchal society, when a man had the right to do with his wife and children whatever he wished. Of course the modern legal system -- such as that of the Dayton criminal defense attorney, for instance -- affords women equal rights, but at the time, many Roman men believed this independence had led increased divorce, sexual promiscuity, and adultery. Roman men also complained that women no longer looked after their own children, but handed them off to wet nurse slaves. But despite Augustus' attempt to bring the law back to the good ol' days, the Roman historian Tacitus reported that the social reform laws were never very effective and had also brought on the wrath of many of the higher-classed Romans who felt the government shouldn’t be intruding into their private lives. Not only that, Augustus ended up exiling his own daughter and granddaughter based on these laws, and this only brought him further denouncement. Any Dayton criminal defense attorney today would find Augustus' social reform laws antiquated and easily defeated in court.

As for the vomitoriums, the popular image of Romans setting aside a room within the amphitheatre solely towards the disgorgement of food is just a myth. After all, how many people could possibly want to dedicate an entire room to sharing digestive tract movements with friends and fellow spectators? Vomitoriums were passageways engineered to “vomit” out spectators onto the streets quickly and efficiently. Although there are some known cases of Roman elites purposely inducing vomiting, there were no masses of potbellied aristocrats emptying their stomachs in the amphitheatre for the chance to continue out-eating one another in orgiastic competition.

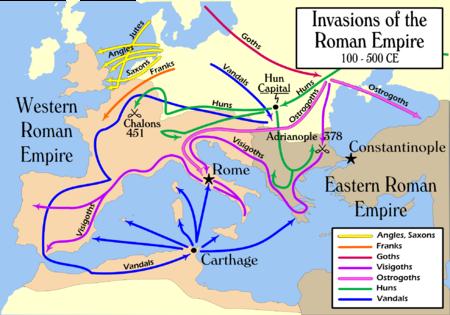

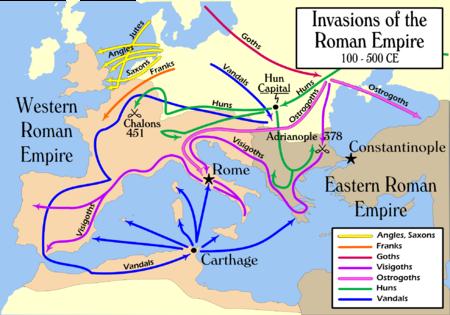

So why couldn’t the Roman Empire endure the German nomads overrunning it’s borders? Actually, it did. The city of Rome was sacked by the Visigoths in 410, was nearly overrun by Atilla the Hun in 452, and was sacked again in 455 by the Vandals, yet the western empire continued to be ruled from the coastal town of Ravenna in Italy. The only thing that happened in 476 was that a German officer in the Roman army, Odoacer, deposed what later historians would dub the last Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustus. Romulus had only been a young figurehead, nicknamed ‘Augustulus,’ or ‘Little Augustus.’ He had been propped up because his father, Orestes, was too German to give himself the title of Emperor after he rebelled against Emperor Julius Nepos and took control of Ravenna. Thus, the Roman Empire supposedly “fell” when one German peacefully relieved another German of control of an Italian city that was not Rome.

But neither Emperor Zeno, who ruled the Eastern Roman Empire until his death in 491, nor his rival to the throne, Basiliscus, would have considered Romulus to have been the last emperor of the Roman Empire. In fact, neither of them even recognized Romulus as Emperor of the West, seeing as the legitimate emperor, Julius Nepos, was still alive and well and ruling in Dalmatia! Odoacer could have ruled as an agent of Zeno, but instead sent the imperia regalia back to him and settled for the title King of Italy. Odoacer even minted Roman coins in the name of Emperor Julius Nepos up until he had the western emperor assassinated in 480, four years after what is generally agreed on as Rome‘s fall. Yet the Eastern Roman Empire continued to be ruled from Constantinople for almost another thousand years. Later historians would refer to this as the Byzantium Empire, but it’s subjects called themselves Roman and their empire Romania, and they had been granted full rights as Roman citizens ever since Emperor Caracalla’s Edict of Antoninus in 212. Latin continued to be the official language of the east until the Emperor Heraclius re-established the Greek language in 610 along with other major reforms.

The eastern emperors themselves had continued an unbroken succession of rule ever since Constantine had defeated Mexentius at the Battle of Milvan Bridge in 312. This had put down a Roman rebellion against it’s own empire when Diocletian and Galerius, emperors from Illyria in the east, decided to submit the city of Rome to taxes like every other city in the empire. Constantine then disbanded the Praetorian Guard that had made and unmade emperors ever since Augustus had had them formed, converted to Christianity, and moved the capital from Rome to Constantinople in 330. He gave special privileges to Christians in order to create a single empire-wide religion, and a very large proportion of the eastern empire converted with him. But Rome the city had really lost control of their Empire even prior to that, when Diocletian divided the Empire among four tetrarchs in 293. Two senior emperors each given the title Augustus, and two junior emperors, named Caesar, each ruled from a different city, none of them being Rome.

So it wasn’t the Roman Empire but Western Rome that fell, and it didn’t fall in a day, but what about the picture of heathen barbarians desolating a debauched pagan civilization? One problem with that is that the Roman Empire’s official religion was Christianity and had been since Theodosius the Great illegalized paganism and all forms of unorthodox Christianity in 380. Another problem is that the Visigoths who settled Spain, the Ostrogoths who settled Italy, and Vandals who settled North Africa, were all Christian themselves. This, however, did not help ease any tensions between Romans and Germans as all the German tribes, excluding the Franks, converted to a sect of Christianity that did not accept Jesus as being one with God. They were called Arians by Catholic/Orthodox followers, after an Egyptian bishop from Constantine’s time named Arius.

Although Roman decadence is most often referred to in attempts to denigrate hedonism and perceived sexual perversions, the most famous of the debauched emperors, Caligula and Nero, lived over 400 years before the commonly accepted date of Rome’s fall. Even the lesser known emperors whose twisted libidos were lampooned by ancient Roman historians, such as Domitian, Commodus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus, ruled a good 250 years before the “fall” date. Caligula may have committed incest with his sister and married his horse before making it a Senator, and Elagabalus might have wandered the palace naked while conducting affairs with a Vestal Virgin, the widow of a man he had murdered, and his male slave chariot driver, but the Empire continued to live on.

The stage was set for failure against the German tribes in 376 when the Emperor of the East, Valens, tried to make an alliance with Goths who had been displaced by the Huns by allowing them to settle within Roman borders. However, the Goths were treated like chattel and were often forced to sell their children into slavery for dog meat. The Goths revolted and for 2 years there several battles with no clear winners. The Emperor Valens decided to take matters into his own hands and left Antioch for Constantinople. He sent for reinforcements from the western emperor, Gratian, and sent for his general Sabastian from Italy as well. After Gratian and Sabastian had their own victories on the way there, Valens received word that a 10,000 Goths were moving to circumvent his army at Adrianople, in western Turkey. Although Graitan, Sabastian and Valens’ own generals advised him to wait for the reinforcements, the emperor decided to move forward and attack with about 15,000 men. But just as the Roman army was beaten back from their first attack, the Gothic cavalry returned from grazing and routed the Roman army. The Battle of Adrianople turned into one of the greatest military defeats in Roman history and resulted in a large portion of the Roman army being destroyed. Valens was also killed, possibly by being trapped in burning house. Valens was an Arian Christian, but his brother Valentinian I had been Catholic/Orthodox and had been succeeded by Gratian. Gratian prohibited pagan worship in Rome, much to the displeasure of the Senate, and after Valens died, Gratian replaced him with a Catholic/Orthodox general named Theodosius, and the new emperor of the east made another peace deal with the Goths. He then deposed the Arian bishop of Constantinople, which caused a riot. The Christmas holiday, which had first been popularized in Rome, was promoted in the East as part of the Catholic/Orthodox revival, though highly controversial due to the popularity of Arianism in the east. The Christmas feast largely disappeared after Gregory of Nazianus resigned as bishop in 381, but was reintroduced by John Chrysotom around 400.

The most agreed-upon cause of the loss of Roman power in the west by modern historians is the Germanization of the Roman armies. Theodosius bought peace with the Goths by ceding large tracks of the Balkans and allowing them to settle in Roman land under their own laws. He then began recruiting German regiments under their own officers into the Roman army. The tight disciple and training that had been the hallmark of Roman military victory was being abandoned. Expensive and burdensome Roman armor was set aside while German cavalries started adopting their own lighter version of Roman armor. Thus Roman battles began to look more and more like German tribal warfare.

Much of Rome’s previous cultural identity was destroyed during Theodosius’ reign as he sought to transform the pagan west into the Christian east. Despite the fact that it had been less than 80 years since Emperors Diocletian and his cohort Galerius had inaugurated the worst of the great persecutions against Christianity, the entire empire was now expected to instantly convert to the once-despised religion. Constantine had spent a great amount of time and energy in unifying the church, but now that the church was more unified in structure and popularity, the emperor Theodosius found himself being beckoned by the church rather than the other way around. When Theodosius conducted a massacre of some 10,000 people from Thessalonica in revenge for an uprising, St. Ambrose excommunicated him and refused him communion until he acknowledged his sin of shedding innocent blood. At first Theodosius refused, but was eventually forced into several months of public penance at Milan’s cathedral, giving ample proof of the church‘s political power.

The laws banning the traditional gods from the Roman Empire soon took the form of destroying any and all things pagan. Even though Theodosius was at first against this, arguing that Pagan statues should be left intact and temples should be converted into public buildings, he soon bowed to the church’s pressure. The Theodosian Decrees he issued in 391, which are believed to have been heavily influenced by or credited to St. Ambrose, brought about the destruction of the gigantic Serapeum temple in Egypt and its adjacent library, built in the 200s B.C. in honor of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis. The Latin theologian and historian Tyrannius Rufinus located the destruction in the city of Canopus, but the church historians Sozomen and Socrates of Constantinople placed it in Alexandria. All three make mention of a story, from either 389 or 391, in which the looting Christians were surprised to find symbols so close to the cross: the ankh, the familiar Egyptian symbol of eternal life, and the Tau cross, symbol of Tammuz and root of the letter T. Socrates gives further particulars in his Ecclesiastical History, saying:

“Whilst they were demolishing and despoiling the temple of Serapis, they found characters, engraved in stone, of the kind called hieroglyphics, the which chracters had the figure of the cross. When the Christians and the [Pagan] Greeks saw this, they referred the signs to their own religions. The Christians, who regarded the cross as the symbol of the salutary passion of Christ, thought that this character was their own. But the Greeks said it was common to Christ and Serapis; though this cruciform character is, in fact, one thing to the Christians, and another to the Greeks. A controversy having arisen, some of the Greeks converted to Christianity, who understood the hieroglyphics, interpreted the cross-like figure to signify ‘The Life to come.’ The Christians, seizing on this as in favor of their religion, gathered boldness and assurance; and as it was shown by other sacred characters that the temple of Serapis was to have an end when was brought to light this cruciform character, signifying ‘The Life to come,’ a great number were converted and were baptized, confessing their sins.”

Another toll came to western Rome in the Battle of Frigidus, one of the most important battles in late Roman history. In 392, Gratian’s half-brother and Theodosius‘ brother-in-law, the Western Emperor Valentinian II, was found hanged in Vienne, Gaul. The Master of Soliders, a German Frank named Arbogast claimed it was suicide, but Theodosius suspected him and stopped responding to Arbogast’s attempts to contact him. As it appeared increasingly likely that Theodosius was preparing for a fight, Arbogast raised a former rhetorician named Flavius Eugenius to the throne, backed by the Senate and Praetorian Prefect. Although a Christian, Eugenius was sympathetic to paganism and worked to reopen the pagan shrines that had been closed down by Theodosius, which brought him scathing criticism from the highly influential St. Ambrose. When a delegation from the west came to Constantinople asking for Theodosius to recognize Eugenius as emperor, Theodosius was noncommittal, and in 394, he invaded the West. At his side was Stilicho, a half-Vandal and half-Roman general, and the Gothic chief Alaric, who would lead the sacking of Rome 16 years later. Against Theodosius, Eugenius marched the armies of the west under the banner of Hercules Invictus (“Hercules the Invincible”). Theodosius won the battle, but the civil war was very costly on both sides. The west submitted to the east, and Theodosius became the last emperor to rule over a united empire.

Upon his death, Theodosius had the empire divided between his two incompetent sons, Honorius and Arcadius, at which point they began to fight against one another for complete control. Concerned more with correct religion than the strength of the empire, the emperors only promoted Orthodox Christians into military positions. Stilicho became the de facto commander-in-chief of the West, and his daughter married Honorius to strengthen the alliance, but the political squabbling of Theodosius’ sons hindered his efforts. Under pressure from the Huns, the Visigoths, or “Western Goths,” raided the Roman city of Thrace, with the former Roman general Alaric leading them. When the Visigoths moved into Italy, Honorius moved the capital from Milan to Ravenna. The army that had won the Battle of Frigidus was still assembled and the still-loyal Stilicho led it towards the enemy, only to have Arcadius order the eastern troops back home, leaving Honorius with half an army. Despite this, Stilicho was able to defeat Alaric’s forces two years later in Macedonia and put down a revolt in Count Gildo, Africa. He fought his own countrymen, the Vandals, and then fought two more battles against Alaric. But despite all these victories, many still saw him as a barbarian and an Arian heretic, and he was accused of intriguing with Alaric to depose Honorius to put his own son on the throne. Stilicho surrendered to Honorius in Ravenna, seemingly confident that he would disprove the charges. There, Honorius had him executed and the effect was disastrous. Stilicho’s mostly German army switched allegiance to Alaric and the Visigoths, who then marched into Italy. The indecisive emperor continued to switch advisors, alternating between plans of retaliation and reconciliation, infuriating his Roman contemporaries. Britain sent message to Rome for help from their own German incursions, but being too preoccupied with his own problems, Honorius wrote back that they would need to fend for themselves. Then the Visigoths sacked Rome. There is a story that says when Honorius first heard that Rome had perished, he thought it was in reference to his favorite chicken, and the emperor recalled just seeing it earlier, eating out of his hand.

St. Augustine and the Cities of God and Man

Many blamed Rome being sacked on Christianity and the abandonment of the empire’s original gods. St. Augustine’s book, The City of God, was written explicitly to counter this argument. Born in a Roman city in North Africa, St. Augustine had been a follower of Manichaeism, a religion based on the Babylonian prophet Mani that was popular in Africa at the time. After that he followed Neo-Platonism, a philosophy based on Plato and the more recent philosopher Plotinus, but with the help of his mother and St. Ambrose, St. Augustine converted to Christian Orthodoxy. When his mother had arranged a societal marriage for him, he put away his concubine of over 15 years, who had borne him a son, but struck up another affair while he waited for his young wife to come of age. In what‘s considered to be the first autobiography in Western Europe, Augustine admits in his book Confessions to living a hedonistic lifestyle with one of his most famous prayers being, “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.”

But at the age of 32, he heard the voice of a young girl tell him to pick up a volume of Paul’s epistles and reads “Make no provision for the flesh and its appetites.” Augustine gave up his career in rhetoric and his teaching position in Milan, devoted his life to celibacy, and had himself and his son baptized by St. Ambrose. St. Augustine saw himself as a kind of reformed Paul, who had also come to see the error of his ways. He was made bishop of Hippo in Africa, where he became a famous orator against Manicheans. Augustine would conduct a literary feud with the Manichean, Pelagius, who taught against the Catholic/Orthodox teaching on Original Sin. The question was important in Carthage at the time because of the question as to whether un-baptized babies go to hell. Augustine believed they did but it was a hell of the “mildest of conditions.” A decree from the bishop of Rome, Boniface I, upholding original sin subsequently led to the exile of 18 Italian bishops for the Pelagian heresy.

The theme of The City of God was a contrast between the city of man, which was formed by love of self even to the contempt of God, with that of the city of God, which was formed by love of God even to the contempt of self. In it, he argued that many of the same accusers had used Christian sanctuaries to save their own lives while Rome was being attacked. “The reliquaries of the martyrs and the churches of the apostles bear witness to this; for in the sack of the city they were open sanctuary for all who fled to them, whether Christian or pagan.... And they ought to attribute it to the spirit of these Christian times, that, contrary to the custom of war, these bloodthirsty barbarians spared them, and spared them for Christ's sake…”

St. Augustine argued that those who belong to the city of God are strangers to this world and should not concern themselves with piety and humility, while those who belong to the city of man live according to their own glory and profit. Although Augustine believed that God did bring favor to the good and punish the wicked in this world on occasion, many of the “saints” saw great hardship while many evil men would have to wait until their death to receive their punishment. He used the poverty of the apostle Paul and the book of Job’s famous phrase “the Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away” to show examples of good men who went through great trials and still kept their faith through their detachment to the material world.

“There is, too, a very great difference in the purpose served both by those events which we call adverse and those called prosperous. For the good man is neither uplifted with the good things of time, nor broken by its ills; but the wicked man, because he is corrupted by this world's happiness, feels himself punished by its unhappiness. Yet often, even in the present distribution of temporal things, does God plainly evince His own interference. For if every sin were now visited with manifest punishment, nothing would seem to be reserved for the final judgment; on the other hand, if no sin received now a plainly divine punishment, it would be concluded that there is no divine providence at all.”

The ancient Romans who first founded the Republic, while foregoing many vices and greatly esteemed by poets and Roman counsels, were still only working for the city of man, and so would not share in the heavenly rewards of the Christian.

“So also these [Romans] despised their own private affairs for the sake of the republic, and for its treasury resisted avarice, consulted for the good of their country with a spirit of freedom, addicted neither to what their laws pronounced to be crime nor to lust. By all these acts, as by the true way, they pressed forward to honors, power, and glory; they were honored among almost all nations; they imposed the laws of their empire upon many nations; and at this day, both in literature and history, they are glorious among almost all nations. There is no reason why they should complain against the justice of the supreme and true God- ‘they have received their reward.’” Although his theological reasoning was greatly influenced by Platonism, Neo-Platonism, and Stoicism, Augustine dedicates much of The City of God to arguing against these philosophies, writing that although philosophers acknowledge that people can not be happy unless they partake of the light of the supreme God, being vain in their imaginations, they yielded to popular error and acknowledged that honor and worship should be given to the demons that were the pagan gods. The book would become one of the founding works of Roman Catholicism. St. Augustine, more than any of the other Latin fathers of the early church, built up the traditions of the west in ritual and in canon law and is considered the pre-eminent Doctor of the Church. Even Protestants consider him to be an important source in Reformation theology, with his book acknowledged as an important treatise on the Protestant teaching on salvation through grace from original sin. Protestants, however, in doing so are forced to ignore his sermon to the people of Caesarea, in which he said:

“No one can find salvation except in the Catholic Church. Outside the Church you can find everything except salvation. You can have dignities, you can have sacraments, you can sing ‘Alleluia,’ answer ‘Amen,’ have the Gospels, have faith in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and preach it, too: but never can you find salvation except in the Catholic Church.” In the 18th century classic, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon provides an exhaustive analysis of the factors leading the empire’s demise. Chief among these reasons is the supplanting of the classical tradition of the Roman community with Christian beliefs. No doubt influenced by works like that of St. Augustine, Gibbon saw Christianity as bringing about a mystical ambivalence that translated into neglect towards the real world. In the 38th chapter, Gibbon writes:

"As the happiness of a future life is the great object of religion, we may hear, without surprise or scandal, that the introduction, or at least the abuse, of Christianity had some influence on the decline and fall of the Roman empire. The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of the military spirit were buried in the cloister; a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers' pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes, who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity. Faith, zeal, curiosity, and the more earthly passions of malice and ambition kindled the flame of theological discord; the church, and even the state, were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody, and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny; and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country. Yet party-spirit, however pernicious or absurd, is a principle of union as well as of dissension. The bishops, from eighteen hundred pulpits, inculcated the duty of passive obedience to a lawful and orthodox sovereign; their frequent assemblies, and perpetual correspondence, maintained the communion of distant churches: and the benevolent temper of the gospel was strengthened, though confined, by the spiritual alliance of the Catholics. The sacred indolence of the monks was devoutly embraced by a servile and effeminate age; but, if superstition had not afforded a decent retreat, the same vices would have tempted the unworthy Romans to desert, from baser motives, the standard of the republic. Religious precepts are easily obeyed, which indulge and sanctify the natural inclinations of their votaries; but the pure and genuine influence of Christianity may be traced in its beneficial, though imperfect, effects on the Barbarian proselytes of the North. If the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors."

Atilla's Scourge

When Emperor Honorius died of fluid in the lungs, his closest male relative was his 6-year-old nephew Valentinian III, who was away in Constantinople. When Arcadius’ son, Theodosius II, hesitated in naming a successor, the chief notary, Johannes decided to seize power in the west. Unlike the Theodosian emperors, Johannes accepted all religious sects and was recognized as emperor in Gaul, Spain and Italy, but not Africa. In retaliation, Theodosius II raised up the young Valentinian III to the throne to counter the usurper, despite the fact that Valentinian’s mother Galla Placidia having previously fallen out of favor with her half-brother Honorius and the eastern court. Expecting war, Johannes sent his servant, Flavius Aetius, to the Huns for military assistance, but by the time he came back, Johannes had been betrayed and handed over to Theodosius’ men. Theodosius' men chopped off Johannes' hands and paraded him on a donkey around the city of Aquileia, in modern Austria, before decapitating him. After some skirmishes, Aetius made a deal with Placidia that the Huns would be paid off and go home and he would become commander in chief of the western army.

Count Boniface, the Roman general who had sided with Placidia against Johannes, later fell out of favor with Placidia and was deemed a traitor, possibly influenced by his rival Aetius. It’s said that Aetius told Placidia that Boniface was plotting against her and convinced her to send for him while simultaneously sending a message to Boniface not to appear because Placidia wished to kill him. Rather than surrender and be executed, he started a revolt in Africa, calling in the Vandal king from Spain, Gaiseric the Lame (a.k.a. Genseric). Boniface eventually made peace with Placidia, but by then it was too late. The Vandals had already started their 80,000-man migration into Africa and Boniface was forced to fight them. He was defeated and retreated to Hippo, where Gaiseric put the city to a 13-month siege in 430. St. Augustine, now 76, caught a fever during the third month and died.

Aspar, an Alan from Iran and the Master of Soliders, was sent from Constantinople to reinforce Boniface, forcing Gaiseric to retreat from the siege. But when Boniface and Aspar met the Vandals in the field, they were completely routed, and Aspar was forced to make a generous treaty with the Vandals. Boniface returned to Rome with Placidia planning to use him to replace Aetius. Aetius saw getting rid of Boniface as the only way to stop Placidia from getting rid of him, and so he attacked his rival outside Ariminum, in Italy. Boniface won the battle but suffered a wound, said to have been given by Aetius himself, which would prove fatal several months later. With Boniface dead, this left Aetius the de facto ruler of the west. Placadia restored his official power and his army of Huns were rewarded with the lands of Pannonia in upper Italy.

Aetius would serve Rome with great distinction after this, putting down disturbances in Gaul, Spain, Brittany, and especially Bagaudae, where his call to the Huns to stop Burgandian bandits from raiding the countryside brought about the slaughter of 20,000 people. This would become the basis for the German epic, the Nibelungenlied. But Aetius’ most famous battle was against Atilla the Hun at the Battle of Chalons in 451. Aetius had been a hostage during the early part of his life, at first with King Alaric of the Goths. Aetius was then traded by Rome to the Huns, in return for the 12-year-old Atilla, following a peace treaty with Honorius in 418. Aetius and Atilla had originally been allies, with Atilla sending Huns to Aetius so he could use them to fight the Goths and Bagaudae, but diplomatic efforts from Gaiseric against Rome may have paid off. Atilla and his brother Bleda defeated the Roman armies of the east and then secured an increasingly better tribute from Emperor Theodosius II, the son of Arcadius, in the years 435, 443, and then again in 447 after Bleda’s mysterious death, while eastern Rome was being hit by plagues, famine, and an earthquake that leveled Constantinople’s walls. Although Atilla was well known for being merciless on the battlefield, and he may have killed his own brother to secure his own power, but when the Roman historian Priscus was sent as emissary to Atilla’s encampment in 448, he described Atilla as being soft-spoken and courteous, and wearing clean but unadorned clothes, and eating off wooden plates while his guests dined on plates and goblets of gold and silver.

Atilla had actually been invited to invade the West in 450 by Valentinian’s sister, Justa Grata Honoria, who had proposed to marry him and give him half of Rome as a dowry. She had done this to escape an unwanted engagement to an unimportant senator following a previous attempt by her to seize the throne from her brother. After Valentinian found out about her letter to Atilla, he decided to have her killed but was persuaded by his mother to spare her life and only exile her instead. Valentinian then wrote to Atilla, claiming the marriage proposal was illegitimate, but Atilla sent an embassy from his home base in Hungary to the Roman capital of Ravenna with the warning that he would take what was rightfully his.

Then Theodosius II suddenly died in a horse riding accident. Thodosius’ older sister, Pulcheria, succeeded him to the throne, becoming the first woman to rule as an Empress of Rome. She had previously been very influential with her brother before Thodosius exiled her on the advice of a eunich named Chrysaphius. Chrysaphius tried to take the throne afterwards but Pulcheria allied herself with the German military and him executed. Aspar, the Alan general who had fought the Vandals with Boniface, as well as the Persians, could not marry Pulcheria, because he was an Arian Christian. So she instead married a friend and subordinate of his, a veteran captain named Marcian. Pulcheria and her sisters had previously taken a vow of celibacy so her marriage to Marcian was taken with the understanding that it would not be consummated. She was a devout follower of the Catholic/Orthodox Church and had commissioned the building of many churches in Constantinople, especially to the Virgin Mary. She had also previously convinced her brother to attack the Persians largely because of Christian persecution there and had him destroy all the synagogues in Constantinople and to exile all the Jews. Marcian became the first Roman emperor to be crowned by a bishop, the patriarch of Constantinople, a custom to later be imitated in the west. Marcian drastically reformed the empire’s finances, lowering taxes and putting a stop to certain extravagancies. With Atilla coming into conflict with the Franks, Marcian also repealed the high payments of tribute to the Hun, which made the emperor very popular. But rather than retaliate against the now well-fortified city of Constantinople, Atilla set his sights on Gaul.

Aetius and the Visigoth king, Theodoric, along with Alan, Frankish, and Burgandian allies went after Atilla and his federation of Gepids, Ostrogoths (“Eastern Goths”) and other tribes as Atilla was putting Aureliani, known today as Orleans, to siege. Atilla was forced to retreat and Aetius and Theodoric chased after him, meeting Atilla in the violent Battle of Chalons, in which both sides took major casualties. Theodoric was hit by a spear, claimed by an Ostrogoth named Andag, and may have been trampled by his countrymen. Theodoric’s son, Thorismund, mistakenly entered Atilla’s encampment while fleeing enemy troops and was wounded before his followers could rescue him. Aetius got separated from his men in the darkness and spent the night with his Gothic allies. The next day Aetius put Atilla’s camp to siege, but rather than surrender, Atilla heaped up a funeral pyre to throw himself on it so that the enemy would not have the pleasure of killing him. But when Theodoric’s body was found, Aetius is said to have convinced Thotismund to return home to secure his throne against his Visigoth brothers. Aetius disbanded the Franks as well. All of this is supposedly so that he could collect the war booty for himself and because he feared that if the Visigoths killed Atilla, they would break off their alliance with Rome and become an even greater threat.

Atilla would escape and return to Italy, weakened but still claiming marriage rights to Honoria, sacking many cities and razing Aquileia to the ground. Valentinian III fled from Ravenna to Rome, but stopped at the River Po, where he met with an embassy that included the prefect Trigetius, the consul Aviennus, and the bishop of Rome, Leo I. After consulting with them, Atilla turned his armies back and retreated. Although contemporary reports credit Leo’s moral persuasion as Rome‘s saving grace, precisely what Leo said to the Hunnish king remains a mystery. Other suggestions for Atilla’s turning back was that he had lost too many men from plague and famine and that supplies were low. But once Atilla got back, he began planning another strike against Constantinople. Then he suddenly died in 453 on his wedding night to the latest of a string of wives, either from choking to death from a severe nosebleed while in a drunken stupor, or by being assassinated by his new wife. With Atilla gone, his federation of tribes collapsed, and what was the largest empire in Europe at the time virtually disintegrated overnight.

The First Division of Orthodoxy

The credit given to Leo for saving the eternal city from what the Romans referred to as “the Scourge of God” grew into supernatural proportions, with one anonymous author relating the encounter this way:

Then Leo had compassion on the calamity of Italy and Rome, and with one of the consuls and a large part of the Roman senate he went to meet Attila. The old man of harmless simplicity, venerable in his gray hair and his majestic garb, ready of his own will to give himself entirely for the defense of his flock, went forth to meet the tyrant who was destroying all things. He met Attila, it is said, in the neighborhood of the river Mincio, and he spoke to the grim monarch, saying “The senate and the people of Rome, once conquerors of the world, now indeed vanquished, come before thee as suppliants. We pray for mercy and deliverance. Oh Attila, thou king of kings, thou couldst have no greater glory than to see suppliant at thy feet this people before whom once all peoples and kings lay suppliant. Thou hast subdued, Oh Attila, the whole circle of the lands which it was granted to the Romans, victors over all peoples, to conquer. Now we pray that thou, who hast conquered others, shouldst conquer thyself. The people have felt thy scourge; now as suppliants they would feel thy mercy.”

As Leo said these things, Attila stood looking upon his venerable garb and aspect, silent, as if thinking deeply. And lo, suddenly there were seen the apostles Peter and Paul, clad like bishops, standing by Leo, the one on the right hand, the other on the left. They held swords stretched out over his head, and threatened Attila with death if he did not obey the pope's command. Wherefore Attila was appeased he who had raged as one mad. He by Leo's intercession, straightway promised a lasting peace and withdrew beyond the Danube.

Leo had been a Roman aristocrat and a deacon who had showed himself an able enough diplomat to be sent by Emperor Theodosius II to settle a dispute between Aetius and a prominent general in Gaul named Albinus. The Roman bishop Sixtus III died while Leo was away, and he was unanimously elected to be his successor. Leo worked hard to centralize the Catholic/Orthodox church, fighting against heretical sects. He rebuked the diocese of the city Aquileia in Italy for allowing heretical Pelagians to take communion. He conducted a public book-burning of the writings of the Manicheans, who were secretly meeting in Rome after fleeing from the Vandals in Africa. He wrote a treatise against the followers of the Spanish theologian, Priscillian, who may have been influenced by Gnostic and Manichean doctrines from Egypt. Priscillian had strongly advocated a life of celibacy and asceticism, teaching against slavery, gender discrimination, and the consumption of meat or wine, but when he appealed to Emperor Gratian in 385, he had been executed on the grounds of practicing magic. This was approved by a church synod, although it was strongly protested by St. Ambrose and others. Leo reproached the bishops of Sicily for deviations from the official way to administer baptism. He also wrote works against the heretic, Nestorius, a former bishop of Constantinople who had preached against Mary being called the “Mother of God,” instead of “Mother of Christ.” In 426, Leo sought to assert his control in Gaul over that of Bishop Hilary of Arles, whose predecessor, Patroclus, had been recognized as having supreme primacy over Gaul by Bishop Zosimus of Constantinople. When the bishop of Besancon ignored Hilary’s primacy, Hilary made an appeal to Rome, at which point Valentinian wrote an edict abolishing Hilary’s vicarate, and handing all authority over to Leo.

The political power of the bishop of Constantinople was growing, and had become more influential over bishops in Illyria, what is now the Western Balkans, which had previously acted as a counterbalance in favor of Roman authority. Leo laid down the law in a letter arguing that just as Peter had been given authority over the church, all important decisions regarding the church should be decided by the bishop who sat on Peter’s throne in Rome. In 445, soon after Dioscorus of Alexandria became bishop, Leo wrote to him arguing that he should observe the canons and discipline of the Roman Church. The church of Alexandria was credited to John Mark, the gospel writer and disciple of Peter, and so Leo argued that as prince of the apostles, Peter’s ecclesiastical traditions were superior to those of Mark‘s.

As proof he cited a verse in the Gospel of Matthew in which Jesus gives the Peter his name after the apostle confesses to believing that Jesus is the Christ. “Jesus replied, ‘Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by man, but by Father in heaven. And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.’ Then he warned his disciples not to tell anyone that he was the Christ.” (16:17).

Rome has a long tradition of the Pope being head of the church by virtue of an inheritance from Peter. References to the primacy of the Roman See can be found in the writings of Pope Clement of Rome (95 A.D.), Ignatius of Antioch (107), Irenaeus of Lyons (180), Pope Victor of Rome (190s), Hippolytus of Rome (200s), Tertullian of Carthage (220), Cyprian of Carthage (250), Firmilian of Caesarea (250), and the pagan Roman emperor Aurelia (270). As acknowledged by the Roman Catholic Church, the relationship between the offices of Roman pontiff and other bishops were not the same as it is now, as it gradually evolved over the first millennia. Peter’s execution in Rome has largely been considered nothing but Catholic legend, but in 1950, Pope Pius XII announced that the remains of St. Peter had been found beneath the catacombs of the Vatican. Although there is controversy as to the scientific methods that were used, including accounts of rat, chicken, and pig bones being mixed up with the remains, one carbon dating showed some of the human bones going back to the first millennium A.D.

But if Rome is where Peter was killed, does it mean that Peter’s chair in Rome was meant to be the “rock” on which Jesus would build his church? Peter did not necessarily found only one church. Paul himself founded many churches across the Mediterranean. Judging from references from the New Testament, there is earlier evidence pointing to Jerusalem or Antioch as being Peter’s original home. The Epistle to the Galatians has Paul first meet the “pillars” of Christianity in Jerusalem and the First Epistle to the Corinthians speaks of bringing money back for the poor of Jerusalem. Acts of the Apostles identifies Antioch as the city of the first Christians and the Epistle to the Galatians says that James sent Cephas (who is presumed to be Peter) and some other Christians from Jerusalem to check up on Paul in Antioch. Characteristics of the Gospel of Matthew also give ample reason to believe that it was written for Jewish Christians in the east. In one part of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells his followers not to convert the Greek and Roman Gentiles, and to follow the Laws of Moses even better than the Pharisees do. Unlike the Gospel of Mark, the Gospel of Matthew also makes no insinuation that women have the legal right to divorce their husbands. Many Jewish particulars like this in Matthew’s gospel make scholars believe that this gospel was originally spread throughout Jewish circles in the Levant. The church of Antioch also has a tradition that it was founded by Peter and the city, along with Rome and Alexandria, has always had a special patriarchal position in the early church. Today there are at least 5 patriarchs who claim title over Antioch, 3 of which are in communion with the Roman Catholic Church but are not considered part of the church itself. A sixth claim to the See of Antioch had been held since Crusader times only to die out in 1964. The See of Alexandria also had a long tradition of it’s bishops being referred to as Pope, but does not maintain any doctrine of supremacy or infallibility. The title of Pope was also an early moniker for all priests in the east. The word itself is equivalent to Papa, or ‘Father,’ a title that is also mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew: “But you are not to be called ‘Rabbi,’ for you have only one Master and you are all brothers. And do not call anyone on earth ‘father,’ for you have one Father, and he is in heaven. Nor are you to be called ‘teacher,’ for you have one Teacher, the Christ. The greatest among you will be your servant. For whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.” (23:8).

In 448, the Archmandrite of Constantinople, Eutyches, who was second only to the bishop, was accused of heresy by Domnus of Antioch, Eusebius of Dorylaeum (Turkey) and Theodoret of Cyrus (Syria). Theodoret had been caught up in the middle of the Christological controversy between Nestorius of Constantinople and Cyril of Alexandria. On one hand, Theodoret begged Nestorius to drop his assertion that pronouncing Mary “mother of God” was a heresy, but sided with the Antioch party against Cyril and the Egyptian party, arguing against the accusation that this meant Nestorius believed Christ had two natures. He attended two council that pronounced an anathema, or curse, on Cyril and wrote many polemics against him. Cyril’s successor, Dioscurus, along with Eutyches of Constantinople, and the eunich Chrysaphius, obtained an imperial edict, barricading Theodoret in his own diocese. The Antioch fought back by, with Theodoret considered the be the central instigating force.

Eutyches was reluctantly excommunicated by Flavian, the bishop who had originally installed him, but there was an large public outcry and the emperor Theodosius II convened the Second Council of Ephesus in 449 to determine if Eutyches’ teachings really went against the First Council of Ephesus. That council, held 18 years earlier, had decreed that Jesus was one person with two natures, God and man, which were unified, yet stayed completely distinct from one another, thus denouncing the Nestorian heresy. Eutyches taught that Christ had only one divine nature after the unification and so had a different body than that of other humans. He also claimed to be a faithful adherent to the hugely popular Cyril of Alexandria, who was considered a Doctor of the Church. Cyril had been the driving force against the excommunication of Nestorius, but had died 5 years earlier.

Emperor Theodosius II gave presidency over the council to Dioscurus, bishop of Alexandria, and the successor to Cyril. Flavian, and the other 6 judges who originally excommunicated him were not allowed to vote. Leo sent legates on his behalf with his “Tome,” a letter of official church dogma, but Dioscorus did not allow it to be read, nor was Eutyches’ accuser Eusebius allowed to speak. Not only was Eutyches reinstated, but Flavian, Domnus, and Eusebius were deposed and exiled, and the Alexandrian doctrine of one combined nature after the unification, called Miaphysitism, was approved by the council. Pope Leo, who had originally believed Eutyches was a victim of a misunderstanding, would refer to this council as the “Synod of Robbers.” He excommunicated all who took part in it and reinstated those whom had been exiled, except for Domnus, who preferred to return to monastery life.

Theodosius II refused Leo’s appeals, but after his death, Pulcheria and Marcian allowed Leo to convene another council in 451. However, the council would not to be held in Italy as Leo wanted, but in Nicaea, the site of the first council. It was then moved to Chalcedon, next door to Constantinople, after some had already made the journey to Nicea because Marcian was too busy dealing with the Huns to make the trip. Nearly 600 bishops attended, although almost all of them were eastern. Theodoret was only allowed to attend after pronouncing an anathema against Nestorius. A legate of Pope Leo presided over the council that tried Dioscorus, but the bishop of Alexandria did not attend, telling the Emperor of Rome, “You have nothing to do with the Church,” and was unanimously deposed by all the bishops. Even Juvenal of Jerusalem voted against him, although he had supported Dioscorus in the previous council. Juvenal was rewarded with Jerusalem’s status being raised to that of a patriarchal See, along with Constantinople, thus diminishing the authority of Alexandria and Antioch. But when Juvenal went to take control over his new diocese in Palestine, the monks who favored Dioscorus went into open revolt against him, and only the Imperial army allowed him to take his position. Dioscorus and Eutyches were exiled and all but 13 Egyptian bishops signed Leo’s Tome. A concessionary formula was attempted but failed and the bishops were exiled.

Many other new decisions were put into place as well. Bishops were given more rights against accusations as well as jurisdiction over monasteries and poorhouses. The clergy were forbidden to become involved in business, the military, or multiple churches. Monks and nuns were forbidden to marry and deaconesses had to be at least 40 years of age. Conspiring was forbidden. A bishop could not be demoted, but only removed. And despite the protests of Leo’s legates, it was also decreed in Canon 28 that the See of Constantinople, because it resided with the Emperor and the Senate in New Rome, would be elevated in ecclesiastical affairs to second place after Old Rome. Leo declared Canon 28 null and void since it was against the prerogatives of elder patriarchies of Alexandria and Antioch, was against the decrees of the Council of Nicaea, and treated Rome and Constantinople as equals.

The Oriental churches denied the authority of the entire council and continued with the traditions of Cyril. These beliefs were considered in Rome and Greece to be the same Monophysite (“one nature”) heresy of Eutyches, the belief Jesus had only one divine nature, but the Oriental church distinguished itself from that form, instead calling itself Miaphysite (“united nature“), the belief that Jesus had one nature that was both human and divine, and opposed to the findings of Chalcedon, which counted human and divine as being two natures. This minute divergence on the “hypostatic union” of Christ created a great schism within the church, resulting in the formation of Oriental Orthodoxy, distinct from the great schism separating the Roman and Greek churches in 1054. The Copts continued to elect their own successors after Dioscorus died in exile, and the Alexandrian model also continued to be spread by Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II, most especially in Syria. Oriental Orthodoxy today consists of the Armenian Apostlic Church, the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Eritrean and Ethiopian Orthodox churches, and 3 branches of Syrian Orthodox churches.

Leo “the Great” is named as a saint in Roman Catholic Church, with Juvenal of Jerusalem and Emperor Marcian becoming saints in Greek Orthodoxy, and Dioscorus of Alexandaria a saint in Oriental Orthodoxy. Empress Pulcheria was made a saint in both the Roman and Greek churches and Cyril of Alexandria, “the Pillar of Faith,” and Doctor of the Church, is a saint in all three branches. Nestorius became a saint in the Assyrian Orthodox Church, also called the Nestorian or Chaldean Church.

Rise of the Goths

Although Aetius was able to betrothe his son Gaudentius to Valentinian’s daughter Placidia, the emperor became convinced by the Roman senator Petronius Maximus and his chamberlain Heraclius that Aetius was getting too powerful. Inviting Aetius to the palace to discuss finance, it's said Valentinian slew the general with his own hand in 454. A legend goes that when Valentinian asked someone whether the death was well accomplished, he got the reply, “Whether well or not I do not know, but I do know that you have cut off your right hand with your left.” Much like with the death of Stilicho, the betrayal and murder of a famous general that had saved Rome caused a great amount of dissension. Petronius Maximus failed to be given Aetius’ position as commander in chief, and so he conspired with two Hun followers of Aetius to assassinate Valentinian and Heraclius the next year and became emperor himself. Like most of the other Roman Emperors after him, Petronius is considered to be a “shadow emperor,” never really holding a lot of influence. Neither he nor the next 10 “shadow emperors” would rule for more than 5 years. After Valentinian’s murder the real power went to a German named Ricimer, son of Suebian prince and Visigoth princess, who was content with ruling the area from behind puppet emperors.

When Valentinian’s widow, Licinia Eudoxia, the daughter of Theodosius II, showed favor for another emperor, Petronius forced her to marry him in order to strengthen his position. Much like Valentinian’s daughter, Eudoxia is believed to have appealed for help from outside of Rome. She sent a letter to Vandal King, Gaiseric the Lame, who had taken up raiding the Mediterranean as a pirate from his base in Carthage. The Vandal king’s son Huneric was engaged to her daughter Eudocia, and when the Vandal king sailed into Rome from Carthage, Petronius fled the city. Although the Vandals looted Rome in 455, they didn’t actually commit vandalism as their name would later suggest. Prior to entering the city, Gaiseric met with the highly-praised ambassador, Pope Leo. Leo convinced the pirate king to take what they needed but to leave the city and it’s inhabitants unharmed. The Vandals took with them many of the Jewish artifacts Rome had originally stolen from Jerusalem’s temple back to Africa. There they held Eudoxia and her two daughters hostage for 7 years. In the mean time, Marcian contracted a disease, possibly gangrene after a long religious journey, and died in 457. Pulcheria had died four years earlier, shortly after Atilla’s death. Aspar installed a Thracian named Leo I as the new eastern emperor, and he paid Gaiseric’s ransom, but Eudocia stayed behind as a wife to Huneric.

Avitus, who had been made Master of Soldiers by Petronius Maximus, was on a diplomatic mission to his old student, the Visigoth king Theodoric II, when news of Rome’s fall arrived Theodoric II convinced him to assume the title of emperor but was never completely accepted as one by the people. A military campaign against the Vandals failed and when the German blockade brought a famine in Rome, Avitus was forced to melt down several Roman statues to pay his Gothic bodyguard before disbanding them. No help came from Theodoric II, as he was campaigning in Spain. After being defeated in northern Italy by Ricimer, who had been confirmed by the Roman Senate, Avitus was captured and allowed to become bishop of Placentia but died shortly afterwards.

Ricimer was given the title of Patrician, or high court official, by the eastern emperor, Leo the Thracian, and set up a distinguished Roman general named Majorian as puppet Emperor of the West. Leo seems to have considered Majorian an usurper at first but was eventually convinced to accept Ricimer’s appointment. Majorian passed new laws which are found in the Codex Theodosianus compilation, including local taxation, stopping ancient monuments from being used as building material, and outlawing forced ordination into the priesthood. His attempts to stop abuses seems to have made him a target from his own German officials. He defeated the Visigoth king Theodoric in battle and made an alliance with him, but his naval campaign against Gaiseric the Lame was ambushed after being betrayed by some of his officials. Ricimer later decided Majorian was getting too powerful and forced him to resign. Majorian was killed 5 days later and replaced with Licius Severus, from southern Italy, a virtual non-entity, unacknowledged by Emperor Leo. Licius died in 465, probably poisoned by Ricimer, and for 18 months the West was without an emperor. Ricimer and Gaiseric the Lame convinced Leo to raise a man named Anthemius took the throne. Anthemius married his daughter to Ricimer and secured an alliance with the king of Brittany, but was was defeated in battle by Euric, the younger brother of the Visigoth king Theodoric II. A campaign against the Vandal king Gaiseric failed as well, and when he fell into a sickness while in Rome, he began killing many prominent people in the belief it was some kind of witchcraft. Ricimer and Gaiseric allied together to depose him. Olybrius, who was husband to Valentinian’s daughter Placida, was sent to help Anthemius, but was made emperor against his will by Ricimer. After putting Rome to siege for 3 months, Ricimer sacked the city and killed Anthemius in 472. Olybrius died of natural causes and Ricimer of fever that same year.

Leo had in the meantime been working to detach himself from Aspar and had married his daughter Ariadne to Tarasicodissa, a warrior tribesman from Isauria, a tribe from southern Turkey believed to be ancestor to the Kurds. In 466, Tarasicodissa is said to have exposed Aspar’s son, Ardabur, as being a traitor. Although this weakened Aspar’s position, Leo sent a naval campaign led by a general named Basiliscus against the Vandals in 468 that ended in complete disaster. The next year Gaiseric attacked the Greek city of Epirus and Tarasicodissa successfully expelled them. In 470, Aspar tried to coax Leo into acknowleding his other son, Patricius, as Caesar. When Anagastes, the Master of Soldiers in Thrace revolted that same year, Leo was informed that the riot had been encouraged by Ardabur. In 471, Aspar, Ardabur, and probably Patricius were murdered inside Leo’s palace, from which he was given the nickname “the Butcher.” Aspar’s death brought control of the empire firmly into the hands of Leo, who immediately began to persecute the Arians who had sided with him.

Ricimer’s nephew Gundobad assumed his uncle’s title as Patrician and elevated the Count of Domestics, Glycerius, to the Emperor’s throne without Leo‘s support. Glycerius sent Roman troops into Gaul in 473 and prevented the Visigoths and Ostrogoths from joining forces against Rome. But when Leo sent his step-nephew Julius Nepos to take his place, Glycerius surrendered and was made a bishop of Salona, in Nepos’ homeland of Damatia.

When the elderly Leo died in 474, Tarasicodissa set his son Leo II, up as emperor, with himself as regent. The 7-year-old died of an unknown disease less than a year later, and Tarasicodissa assumed his son’s title, taking the Greek name Zeno. As a foreigner, Zeno was very unpopular, and a revolt fermented by Leo’s widow, Verina, deposed him in 475, replacing him with Basiliscus. Zeno escaped and returned to Constantinople with a larger army 20 months later. Dissatisfaction with Basiliscus helped a general defect, and Zeno’s army was allowed to enter unopposed. Basiliscus was exiled to Phyrgia, in Turkey, and died shortly afterwards. Another general, Illus, discovered another plot by Verina to have him deposed and had her imprisoned. This led to a revolt, headed by her son Marcian and an Ostrogoth warlord named Theodoric Strabo. Illus put down the revolt but later turned against Zeno, possibly because he became opposed to Zeno’s sympathy towards Monophysite Christianity. Illus joined Verina’s side and named another general named Leontius emperor, but Zeno defeated them, and they fled to Isauria, in southern Turkey, where Verina died in 484.

Meanwhile, Nepos made peace with Euric and the Visigoths, but Gaiseric the Lame continued on his pirate raids across Italy’s coasts, making Nepos unpopular with the Roman Senate. His lack of Western support brought his German Master of Soldiers, Orestes, to try and take control of the government in Ravenna, and Nepos was forced to flee by ship back to Dalmatia, where he crossed paths with Glycerius, bishop of Salona, again. Orestes raised his 10-year old son, Romulus Augustus, called Augustulus, also called Momylos, or ‘Little Disgrace,’ to the throne, but lost his city to Odoacer, a Roman officer and chief of the Germanic Heruli tribe.

This marks the official end of the empire in the history books, but relatively little changed. Zeno gave Odoacer the title of patrician and Odoacer acknowledged Nepos as Emperor of the West. Nepos seems to have plotted to get rid of Odoacer, and in 480 Nepos was killed by his own soldiers, possibly with the help of Odoacer and/or Glycerius. Fueling the suspicion of Glycerius’ involvement is a report that Odoacer made the one-time emperor bishop of Milan soon afterwards. But Odoacer soon lost favor with the East as he stopped respecting the rights of Roman citizens in Italy, and with Zeno’s encouragement, the Ostrogoth king, Theodoric the Great invaded his kingdom with a half-Roman, half-German Foederati and defeated him in multiple battles at the Isonzo river, Milan, and the Adda river. Theodoric then agreed to share the kingdom with Odoacer only to betray him in Ravenna, where legend says to he slew Odoacer by his own hand during the celebration. Contrary to what one might expect following the anti-climatic “Fall of Rome” and subsequent “Dark Ages,” this actually brought about 30 years of peace and stability, what historians refer to it as a Golden Age of an otherwise war-torn time period.

Theodoric had lived in the court of Constantinople as a hostage at 8 years old and learned much about Roman law and military tactics from Aspar. He was treated well by Leo I and Zeno and was given the title of Master of Soliders. At the age of 20, Zeno allowed him to return to become king of the Ostrogoths in 488. He allied himself with the Franks by marrying Audofleda, the sister of Clovis I, and having his daughter marry the Visigoth king Eutharic, giving him control over the Visigoths as well. For over 15 years he had fought against Theodoric Strabo until the rival died by accident. With the Ostrogoths united, Theodoric’s political importance increased, and the Eastern Emperor Anastasius bestowed on him the highest honor that could be given to a Roman, that of Council.

After defeating Odoacer, Theodoric allowed the Romans living in his kingdom to live under their law while the Goths lived by theirs. He respected Roman culture, and believed that Romans and Germans could live together in peace. He initiated civic work programs that improved living conditions and fostered agricultural growth throughout the kingdom. He built many great architectural feats in Ravenna like the church of San Apollinaire, which survive to this day. He tried to reach some uniformity between Roman and German criminal law with the Edictum Theodorici of 512, which were highly conciliatory to the Romans. Even though he was an Arian Christian, he was asked to arbitrate between two rival bishops of the Catholic/Orthodox Church in Rome. Theodoric chose Symmachus because he was chosen first and by the majority, but this angered the followers of Laurentius, who had more favor in the east.

Theodoric was tolerant of other religions and allowed everyone in his kingdom to worship as they pleased. When a Christian mob inside Ravenna burned down all the Jewish synagogues, he forced the city to rebuild them at their own expense. This was in stark contrast to Theodosius the Great, who when confronted with a similar problem, planned to order a single burned down synagogue be rebuilt, until St. Ambrose halted the giving of the Eucharist in retaliation. This prompted Theodosius to cancel his investigation and drop the charges, which in turn had led to increased Christian attacks on synagogues.

Zeno died in 491 and his widow Adriane chose a favored court official named Anastasius to succeed him. Like Zeno, he was a Monophysite Christian. Anastasius promised land to meet Theodoric’s needs, but delayed the final agreement until he could travel there himself. Being engaged with the Sassinid Empire, the emperor never made his promised trip. When he died, his position was taken up by the 70-year-old commander of the palace guard, Justin I, who claimed to Pope Hormisdas that he was made emperor against his will. Justin was an illiterate soldier who had little knowledge of statecraft and so surrounded himself with trusted advisors, including his nephew Flavius Petrus Sabbatius, who Justin adopted and renamed Justinian. Justin began working to bring the empire back under the control of one emperor ruling one empire under one religion.

The bishops of the east and west had been mired in controversy over the Monophysite heresy. Most eastern bishops had accepted a statement of faith called the Henoticon, written by bishop Acacius and issued by emperor Zeno in 482 and supported by Anastasius, which would allow the Monophysite heresy in Egypt and Armenia to continue without seeming to violate any orthodox tenets. Western bishops, led by Rome, argued against it because it went against the Council of Chalcedon. After 35 years of excommunicating one another, the church settled the Acacian Schism in 519 by condemning both Acacius and the Monophysites. The church of Constantinople reunited with Rome through a confession of faith called the Formula of Hormisdas, which recognized the primacy of the Roman See and condemned Acacius’ attempt at reconciliation. With the help of the Orthodox Emperor Justin, the Catholic/Orthodox Church now began to rally against the Arians.

When Justin I issued an edict against Arianism and took control of the Arian churches in the east in 523, things began to change for the now aged Theodoric. He wrote to Justin, saying, “To pretend to dominion over the conscience is to usurp the prerogative of God.” He suggested that he might go to war with him in the Arians’ defense, but Justin paid him no heed. Theodosius’ advisor and council, Boethius, who wrote several mathematical texts and the only Latin translations of Aristotle extent from the Middle Ages, was imprisoned when some of his adversaries convinced Theodoric that he was scheming with Justin against him. Boethius maintained his innocence and while in prison wrote one of the most influential books written in Latin, The Consolation of Philosophy, and died soon afterwards. Theodoric then sent the bishop of Rome, John I, to Constantinople against his will to convince Justin to resend his edict. When the bishop returned empty-handed, he was locked up in prison and died soon afterwards. Theodoric was beginning to draw measures to retaliate against Catholic/Orthodox churches in the west, when he died suddenlly at the age of 72. Without his leadership, Theodoric’s coalition fell apart and much of what Theodoric had gained in lands was lost. Rule passed to his grandson Athalaric, and then his elderly nephew Theodahad.

Justinian became co-emperor in 527 about 4 months before Justin I died. He’s been called “the last Roman Emperor,” and is considered a saint in the Greek Orthodox Church. Justinian saw himself as a new Constantine the Great and sought to bring the Empire’s lands back to the way they were during the reign of Theodosius the Great. His uncle Justin had passed a law allowing nobles to marry outside their social class, and this allowed him to marry a former courtesan, Theodora, who had once been a topless mime at the theatre. This was particularly scandalous as theatre courtesans were also known to be prostitutes, but Theodora had long left the theatre.

Justinian went on to pass many laws that led to the death, imprisonment, and confiscation of lands from thousands of Jews, Samaritans, and heterodox Christians, including ones of previous high stature. Jews were not allowed to read Hebrew, build new synagogues, or celebrate Passover if it fell on the same day as Easter. The Catholic/Orthodox church was allowed to seize any land sold or willed to a Jew, pagan, or heretic Christian.

The year 529 was a world-changing year and is a far better delimiter for the end of the Roman Classical Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages than the “fall of Rome“ in 476. In that year, plague and famine killed a large proportion of the east’s population. Several earthquakes also hit the east, one leveling the city of Antioch and much of the city’s inhabitants were slain in a subsequent Persian invasion from the Sassinid Empire. The year 529 also saw Justinian’s closing of Plato’s Academy, causing many of the pagan philosophers to seeking protection in Persia, resulting in many Greek philosophical and scientific treatises only surviving through Persian and Arabic translations. When a Samaritan revolt was crushed by Justinian that same year, it led to death and enslavement of tens of thousands of people, bringing about a near genocide of the Semitic people. Justinian may have been a saint but he was no Good Samaritan.

Procopius of Caesarea, a historian and lawyer who worked for Justinian’s prime general, Belisarius, is the stated author of a book called The Secret History, which was discovered in the Vatican Library in 1623. It’s existence had been known previously in book listings, and most scholars believe it was genuinely written in the 550s or early 560s:

"As soon as Justinian came into power he turned everything upside down. Whatever had before been forbidden by law he now introduced into the government, while he revoked all established customs: as if he had been given the robes of an Emperor on the condition he would turn everything topsy-turvy. Existing offices he abolished, and invented new ones for the management of public affairs. He did the same thing to the laws and to the regulations of the army; and his reason was not any improvement of justice or any advantage, but simply that everything might be new and named after himself. And whatever was beyond his power to abolish, he renamed after himself anyway…….. Moreover, while he was encouraging civil strife and frontier warfare to confound the Romans, with only one thought in his mind, that the earth should run red with human blood and he might acquire more and more booty, he invented a new means of murdering his subjects. Now among the Christians in the entire Roman Empire, there are many with dissenting trines, which are called heresies by the established church: such as those of the Montanists and Sabbatians, and whatever others cause the minds of men to wander from the true path. All of these beliefs he ordered to be abolished, and their place taken by the orthodox dogma: threatening, among the punishments for disobedience, loss of the heretic's right to will property to his children or other relatives. Now the churches of these so-called heretics, especially those belonging to the Arian dissenters, were almost incredibly wealthy. Neither all the Senate put together nor the greatest unit of the Roman Empire, had anything in property comparable to that of these churches. For their gold and silver treasures, and stores of precious stones, were beyond telling or numbering: they owned mansions and whole villages, land all over the world, and everything else that is counted as wealth among men. As none of the previous Emperors had molested these churches, many men, even those of the orthodox faith, got their livelihood by working on their estates. But the Emperor Justinian, in confiscating these properties, at the same time took away what for many people had been their only means of earning a living. Agents were sent everywhere to force whomever they chanced upon to renounce the faith of their fathers. This, which seemed impious to rustic people, caused them to rebel against those who gave them such an order. Thus many perished at the hands of the persecuting faction, and others did away with themselves, foolishly thinking this the holier course of two evils; but most of them by far quitted the land of their fathers, and fled the country. The Montanists, who dwelt in Phrygia, shut themselves up in their churches, set them on fire, and ascended to glory in the flames. And thenceforth the whole Roman Empire was a scene of massacre and flight."

Justinian surrounded himself with “new men” of great merit rather than those of the aristocratic ranks. One of these men was Belisarius, commanding both Romans and Huns, and considered to be one of the greatest generals of all time. Through effective strategy he was able to defeat a much larger Persian army in the Battle of Dara, but a defeat in the Battle of Callincum on the Euphrates led to Justinian paying a heavy tribute for a peace treaty. When the Nika chariot race riots broke out in Constantinople, fueled by adversarial Senators and high taxation, Belisarius put down the rebellion in a massacre that killed 30,000 people and burned half the city, yet saved the emperor from having to flee. The general was then sent to fight against the Vandals in North Africa. Ten miles outside Carthage, Belisarius defeated the Vandal king Gelimer in the Battles of Ad Decimum and again in the Battle of Ticameron, ending Vandal dominance in Africa. He then returned to Constantinople and marched the spoils of the Jerusalem Temple taken from Carthage along the streets of Constantinople in a Roman Triumph.